As the debate over removing the Snake River dams churns, tribes quietly lead the way in reintroducing salmon in the Upper Columbia River System

This is possibly the second chinook salmon alevin found in Tshimakain Creek, shown last Wednesday near Wellpinit, Wash. (Tyler Tjomsland/The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

It was raining when Casey Flanagan netted history. For the second time in as many months, no less.

Flanagan, a Spokane Tribal fish biologist, was bent over a large stainless-steel cone floating on two pontoons anchored by steel wires to trees onshore on Wednesday when she made the discovery.

The device, called a screw trap, was bobbing in the frothy spring-runoff waters of Tshimakain Creek, also spelled Chamokane Creek, on the eastern edge of the Spokane Indian Reservation. A hundred yards away, the creek flowed into the Spokane River, just downstream of Long Lake Dam.

The creek poured through the cone, spinning fins like a large cake mixer. But instead of mixing dough, the device shunts any fish, insects or debris into an underwater holding tank.

“Oh, there is a redband right there,” Flanagan said, netting a small native trout from the murky trap and expertly putting the fish into a waiting bucket of water.

Another redband trout and several aquatic stoneflies loitered in the bucket.

Then she swept the bottom of the trap again and raised the net up. Small sticks and other detritus lined the bottom.

Sifting through the debris, she gasped. We just found one, she said, the excitement infectious. The two other biologists with her – Calvin Fisher and Tamara Knudson – crowded in.

In the net was a small, knuckle-length fish. Other than a salmon-pink sack attached to its belly, it was pale and translucent.

“Get him in the bucket, make sure he survives,” Fisher said.

“We’ll give him a minute,” added Knudson. To which, Fisher responded, “It’s a good day!”

The fish darting at the bottom of that 10-gallon bucket represents a biological and cultural victory. It’s most likely a young chinook salmon (a chinook alevin) taking its first steps in a multiyear journey to the ocean.

Casey Flanagan, right, a water and fish project manager checks a screw trap on Wednesday, March 24, 2021, on Tshimakain Creek near Wellpinit, Wash. (Tyler Tjomsland/The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

Likely, it hatched just upstream of the floating fish mixer, one of the first offspring from 20 salmon nesting spots tribal biologists found last year after they’d released 750 yearling chinook in Tshimakain Creek in 2020.

But more importantly, it’s the second naturally spawned chinook alevin found in this stretch of dam-blocked river in more than 100 years, proving yet again that salmon can survive in the Upper Columbia River system. Tshimakain Creek was once an important salmon fishing spot for the Spokane Tribe. When Little Falls Dam was built in 1911, it blocked the migratory chinook salmon from returning to their birth stream to spawn.

No one cried as this little miracle swam around at the bottom of the bucket Wednesday.

But the rain pouring down made it hard to tell for sure.

‘A sexy concept’

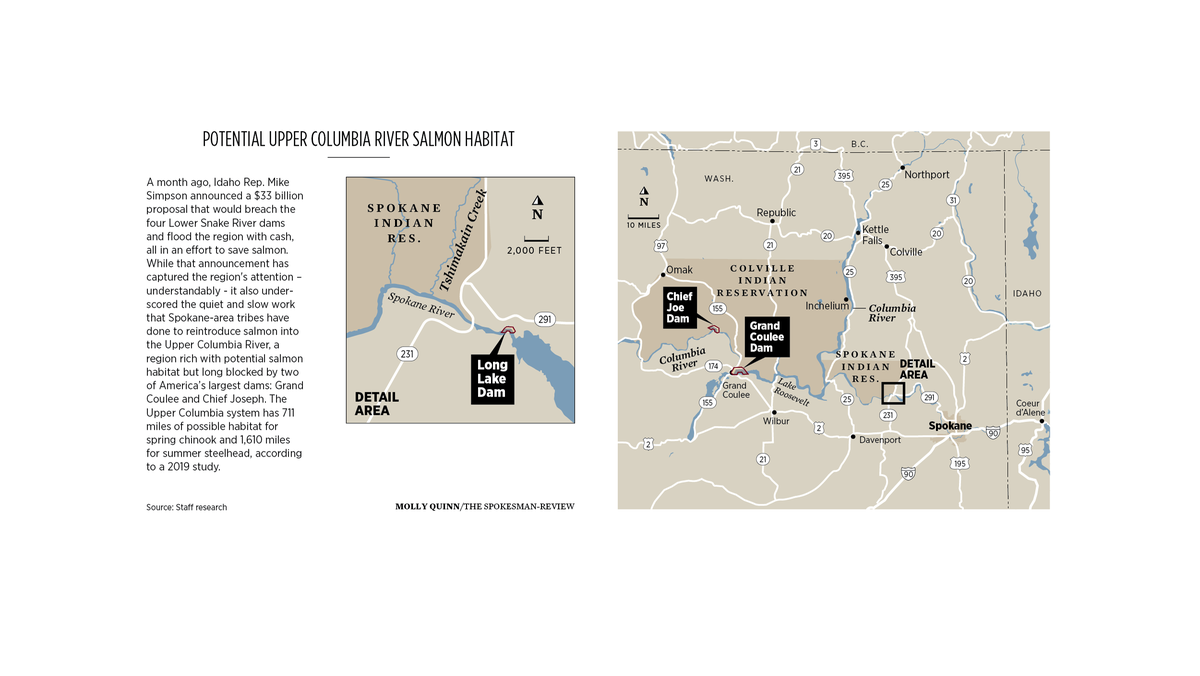

A month ago, Idaho Rep. Mike Simpson announced a $33 billion proposal that would breach the four Lower Snake River dams and flood the region with cash, all in an effort to save salmon.

Since then, his idea has been praised and attacked by both farmers and environmentalists. It has raised questions about power, clean energy and reliability, and faces an uncertain political future.

All that noise – as understandable as it is – has underscored the quiet and slow work that Spokane-area tribes have done to reintroduce salmon into the Upper Columbia River, a region rich with potential salmon habitat but long blocked by two of America’s largest dams: Grand Coulee and Chief Joseph.

Unlike the restoration efforts on the Snake River, the five tribes that are working to reintroduce salmon in the Upper Columbia are sidestepping the dam issue.

“We’re not asking for operational changes,” said Brent Nichols, fisheries manager of the Spokane Tribe of Indians. “That’s one of the big messages we are trying to get out there. We’re not asking Grand Coulee to change how they operate Grand Coulee … Grand Coulee is the lynchpin of the Columbia River system. We recognize its importance in the hydropower system. We also recognize that there are technologies and ways to move salmon and fish around the dam, and get them back up here to the blocked area.”

Instead, the tribes are showing, steadily, scientifically and systematically, that salmon can live and spawn in these upper waters. That work has often flown under the radar.

“The Snake River and the dam removal is certainly a very charismatic and, for lack of a better word, a sexy concept,” said Conor Giorgi, the anadromous program manager for the Spokane Tribe of Indians. “And for whatever reason, reintroduction upstream of Chief Joseph and Grand Coulee hasn’t received the attention.”

Attention or not, the Upper Columbia United Tribes – which include Coeur d’Alene Tribe of Indians, Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, Kalispel Tribe of Indians, Kootenai Tribe of Idaho and the Spokane Tribe of Indians – started this work in 2015. That’s the year they published a paper outlining a phased approach to reintroduction of salmon upstream of the two dams.

Phase 1 of that work wrapped up in 2019 and found, among other things, that there is still suitable habitat for salmon.

Quite a bit, in fact.

Once awash with fish

The Upper Columbia system has 711 miles of possible habitat for spring chinook and 1,610 miles for summer steelhead, according to a 2019 study. Of that spring chinook habitat, 80% was deemed to be highly productive while 53% of the steelhead habitat was judged to be highly productive.

The good news continues, a drumbeat of hopeful projections:

• Currently accessible tributary habitats could produce 2,300 adult steelhead and 600 spring chinook, and 8,500 summer and fall chinook.

• The Rufus Woods Lake and the Transboundary reach, along the Canada-U.S. border, could support between 800 to 15,000 and 5,000 to 61,000 adult spawners, respectively.

• The Sanpoil River and nearby tributaries could produce between 34,000 to 216,000 Sockeye, tribal research indicates.

• Sockeye smolt capacity for Lake Roosevelt ranges from 12 million to 49 million.

All of which makes sense, Flanagan said, if you consider the history.

The Spokane River, and the Upper Columbia River system in general, was awash with salmon. Researchers estimate Upper Columbia River tribes caught 644,469 fish a year. All those fish weighed, roughly, 6.8 million pounds, which was good because Native people ate 948 pounds of salmon per capita..

That litany of good news was one of the big takeaways from Phase 1 of the reintroduction study.

Now, the tribes are entering Phase 2, which will introduce tagged salmon into the system to test the habitat and survivability estimates developed in Phase 1. Phase 2 will also focus on figuring out the best method for getting fish up and over Grand Coulee and Chief Joseph dams. All of that, Giorgi said, should take at least five years.

A key step in that process will be the release of 750 yearling chinook in 2022. Each will be tagged with a passive acoustic tracker that pings stationary receivers as the fish make their way downstream. That data will allow the Spokane Tribe and others to see how many fish survive going through, or over, each dam, as well as how many survive passage through the reservoirs, Giorgi said.

The tribe also plans to release tens of thousands of tagged yearling chinook to assess survival through the main stem of the Columbia River downstream of Chief Joseph Dam.

Phase 3 of the plan is to construct permanent passage facilities for fish coming up and down the river, Giorgi said.

At the same time, the tribes have had several cultural releases. The Spokane Tribe released 750 yearling chinook in 2019 and 2020. The Colville Tribe released about 60 salmon above Chief Joseph and Grand Coulee in 2019.

The chinook alevin found on Tshimakain Creek Wednesday is most likely a descendant of one of these released fish.

Challenges remain

While that is all good news, the challenges remain substantial.

Sure, there is good habitat for salmon in the upper reaches, but getting to it remains impossible. Since the Grand Coulee and Chief Joseph dams were built (without fish passage) in the 1930s and 1950s, respectively, salmon have been blocked from returning to spawning beds in the upper Columbia River. And that’s not to mention the various dams up and down the Spokane River – five up to the Spokane Falls – none of which have fish passages.

The tribe will look at a variety of ways to get fish up and downstream of the dams. Current options include the Salmon Cannon, a flexible pneumatic tube that shoots salmon over dams and other obstacles, trucking, helicopters or even fish ladders. The Phase 2 study will help determine which is the best option and where.

Even if passage up and down the dams is solved, plenty of dangers remain for a young juvenile salmon trying to make it to the ocean. Reservoirs like Lake Roosevelt are difficult to navigate, as salmon smolts in particular depend on the downstream current to pull them along. Plus, predatory fish like walleye, bass and increasingly Northern Pike can decimate native fish populations.

And even then, making the transition from the reservoir into suitable spawning habitat can be difficult.

A good example is Blue Creek and its confluence with the Spokane Arm of Lake Roosevelt. The reservoir can fluctuate up to 80 feet. That back-and-forth erodes soil and washes away the small gravel and pebbles that salmon need to build the nests in which they spawn. It also removes still water, which salmon and other fish species need to rest in.

“What you really need for salmon and steelhead and trout is, you need resting habitat as you’re going upstream,” Flanagan said. “And that is what is eliminated by a drawdown time.”

That’s not to mention the as-yet unconfirmed effects of a changing climate. One early indicator Flanagan has seen is a proliferation of nonnative crayfish in Columbia River tributaries. While checking a trap Wednesday on Blue Creek’s confluence with the Spokane arm of Lake Roosevelt, she found 10 crayfish and no fish.

And of course, funding for the work remains an issue.

“Right now, that’s the biggest obstacle for reintroduction, finding the funding to do the studies and the subsequent work,” Giorgi said. “It already has been a largely tribally funded effort.”

Still, Brent Nichols, the Spokane Tribe’s fisheries manager, is confident.

“The biggest pushback we’ve been hearing from folks is that juveniles won’t be able to navigate through Lake Roosevelt,” he said. “And we’ve already dismissed that concern twice now with our small test releases.”

The best example?

In 2017, 752 yearling summer chinook were released into Tshimakain Creek, all tagged and tracked. They headed downstream, passing either through the dams’ turbines or over spillways. In 2019, one of the released fish made its way back upstream, in a doomed effort to return to its birthplace. In July 2019, the intrepid fish made it up the final fish ladder on the Columbia River at Wells Dam. Chief Joseph Hatchery workers caught the adult chinook and returned it the Spokane Tribe, where it is now mounted in the tribes fishery office – a reminder of the work they’ve done and the work that remains.

‘A conceptual idea’

How Simpson’s proposal would impact tribal work along the Upper Columbia and Spokane Rivers is yet to be seen.

Many of the individual regional tribes involved in the salmon reintroduction work declined to comment on Simpson’s proposal. The Colville Tribes declined, although they did write a letter of support when the proposal was first announced. A spokeswoman for the Coeur d’Alene Tribe said that “at this time the Tribal council has not taken a position on the dam matter proposed by Simpson.”

As for the Spokane Tribe, chairwoman Carol Evans said in an email that the tribe is “heartened by Congressman Simpson’s courage to recognize the continued flawed approach the Federal Government has used in addressing the negative impacts of the Federal Columbia River Power System to date.”

She added, “This system that has produced immense wealth for the Columbia River Region at the expense of the salmon, steelhead, and lamprey that the Spokane Tribe and many other Tribes in the Columbia River Region relied upon until the construction of Grand Coulee Dam. Although, the proposal headlines with the removal of the four Snake River Dams, Congressman Simpson’s concept could speed the implementation of returning salmon, steelhead, and lamprey to the Upper Columbia River.”

In a news release, Simpson pointed out that “states will have a larger say moving forward in setting water policy and allocating federal funding in the future. These provisions are crucial to the balance that must be found in any workable solution to this long-standing problem.”

For his part, Nichols said he’d be interested in reading whatever legislation comes out of the proposal, noting that right now it’s still just a concept.

‘Go, baby fish, go’

Back at Tshimakain Creek on Wednesday, Flanagan and the other biologists took photos and videos of the small chinook alevin and then released it.

Unlike the first chinook alevin that she caught, Flanagan could let this one go. She kept the first one because the only way to 100% positively identify the species is to count its anal fin rays, a process that kills the fish.

“It broke my heart,” Flanagan said of that necessity. “It broke my heart.”

But science can be brutal, and it was worth knowing for sure that it was a chinook. And she is confident that this second alevin is a chinook as well. It’s the right size, the right time of year and it’s only 100 yards downstream from a documented salmon nesting spot, known as a redd.

And so, they found a calm patch of water and released the tiny fish with a hope and prayer. The creature will grow larger, until it has used up all the nutrients held in the salmon-pink sack on its belly. Then, once it can eat on its own, it will head toward the ocean, navigating reservoirs, predators and dams.

It’s still raining when the chinook alevin hits the water and, as if aware of the many dangers ahead, darts into the shadows, disappearing into the murk.

“Go, baby fish, go,” said Tamara Knudson. “All right, fishy. Survive. Do it.”