Rainbow revival at Lake Pend Oreille

Carson Jeffres, right, with his cousin Nathan Jeffres, of Sandpoint, holds a 22-pound rainbow he caught last year in Lake Pend Oreille. (COURTESY PHOTO)

The fish that made Idaho’s largest lake famous are getting back to trophy form.

For 15 years, the Idaho Fish and Game Department has been aggressively reducing the number of invasive lake trout in Lake Pend Oreille to help bring back the popular kokanee fishery that was crashing at the end of the 1990s. Fishing for kokanee was closed in 2000 until they were declared recovered in 2013, when fishing for the “silvers” reopened to the delight of anglers who love their red meat.

Meanwhile, the thriving kokanee fishery also has been a feast that’s fueled impressive growth in rainbows and bull trout.

“All kokanee year classes totaled about 11 million in 2019, the high point since the population bottomed out in the early 2000s,” said Andy Dux, Panhandle Region fisheries manager. “Last year, the kokanee population was roughly 7.5 million, still a very high level.

“When kokanee densities are high, their average size is smaller,” Dux said, noting that fish in the 8- to 10-inch range, while still good for smoking, aren’t as appealing to anglers and harder to catch. “The flip side is that rainbows and other predators do very well when prey of that size is abundant.

“It takes six to 10 years for a rainbow to reach 20-plus pounds. The rainbows out there now have lived their entire lives with abundant kokanee. That’s why the trophy fishery has moved to the next level.”

Carson Jeffres, right, with his cousin Nathan Jeffres, of Sandpoint, holds a 22-pound rainbow he caught last year in Lake Pend Oreille. (COURTESY PHOTO)

Anglers have been proving the point. Among the numerous catches of 10- to 20-pound trout, a growing number of beefy bruisers is being landed from Lake Pend Oreille.

In October 2019, Sophie Egizi, 8, reeled in a 36.5-incher to break Idaho’s catch-and-release record for Gerrard rainbow trout.

Last spring the lake produced a 29-inch-long catch-and-release record bull trout caught by Aaron Fox. In late August, Ed O’Hara broke that record with a 31-inch bull trout.

In November, Jenny Howerton won the annual fall derby, sponsored by the Lake Pend Oreille Idaho Club (LPOIC) with a 25.2-pound rainbow. The top rainbow in the Halloween Derby weighed 25.6 pounds.

“The top several prize winners in the Thanksgiving Derby last year had fish ranging from 20 to 26 pounds,” Dux said. “When kokanee numbers were at their lowest (the state offered a bounty on rainbows for a few years during that period), derby anglers were struggling to catch rainbows over 10 pounds.”

In January, a state catch-and-release record for bull trout was set again, this time by Matthew Lutzke, who was fishing with Pend Oreille Charters. It measured an impressive 39 inches long. The scale on the boat registered 31 pounds before the fish was released, as required for bull trout.

“That’s only a pound shy of the certified world record bull trout from Pend Oreille that was caught in 1949,” Dux said. “This is one more example of the trophy potential that exists in the lake.

“More 25-plus-pound fish were caught in 2020 than in any year since the early 1990s. Rainbow anglers have been thoroughly enjoying the fishery, but I don’t think enough folks realize how incredible it is right now. Without exaggeration, I’m not sure you can find a better trophy rainbow fishery on the planet.”

Lake became famous

An accident more than 100 years ago set the stage for Lake Pend Oreille’s legendary fishing status. In 1916, Montana imported chinook salmon eggs from a Whatcom (Washington) County hatchery to raise and stock in Flathead Lake. Somehow, sockeye eggs were mixed in and the combination was released, according to a 2012 interview with Jim Vashrow, Montana’s former regional fisheries manager in Kalispell.

The result was landlocked sockeye salmon, which are known as kokanee.

Fisheries biologists say a 1933 flood likely flushed kokanee down the Flathead River to the Clark Fork and into Lake Pend Oreille in large enough numbers to start a fishery that became wildly popular by the late 1930s.

Kokanee provided a forage base that fattened native bull trout and paved way for the introduction of Gerrard rainbow trout into Lake Pend Oreille in 1941. The Kootenay Lake strain of British Columbia’s Kamloops rainbows, called the Gerrard, was introduced to Lake Pend Oreille in 1941.

“Gerrards get big because they are piscivorous (fish-eating) and grow longer because they become sexually mature a little later than other rainbows, typically at 6-8 years of age,” Dux said.

Sandpoint businesses cashed in on the publicity as the first huge Gerrards started spinning the scales in 1945. The world-record 37-pounder caught in 1947 by Wes Hamlet of Coeur d’Alene captured international attention after the fish was boxed and sent to New York to be photographed with Gen. Dwight Eisenhauer.

Step too far

After Canada had initial success with introducing mysis shrimp in Kootenay Lake to boost kokanee and grow even larger rainbows, fishermen encouraged Idaho Fish and Game to follow suit in Lake Pend Oreille in the 1960s. A disaster gradually ensued.

Within a few years, biologists in Canada and Idaho realized the mysis shrimp would outcompete the kokanee for daphnia, tiny plankton that are critical to kokanee diet. Compounding the problem, the shrimp were a boon to invasive and predatory lake trout, also known as mackinaw, that would find their way into Lake Pend Oreille from Montana.

By the 1990s, it was clear that lake-level fluctuations behind Albeni Falls Dam, completed in 1955, and the introduction of mysis shrimp were the source of the kokanee decline. But in such a large lake, fish managers had few recourses.

“If we can keep the lake trout numbers down and keep the kokanee numbers up, we’ll be able to turn our attention back to both of those major issues,” Dux said in 2012, when he was the lead research biologist and advocate for gillnetting the predators. “Introducing the shrimp was a mistake, but they’re here to stay.”

Partnerships involved

The LPOIC has organized fishing derbies targeting the trophy North Idaho rainbows since 1949 while being steadily involved in promoting and supporting the lake’s fishery.

Ryan Roslak of Athol, Idaho, fishes every month from his boat based at Bayview, and works for the fishery year-round, too.

“I fish catch-and-release, for the thrill of the hunt,” said Roslak, the club’s representative on the Clark Fork Dam relicensing program committee. “There’s nothing better than hooking into one of those big ones.”

Trolling for trophy trout is a gear-intensive undertaking. This time of year, he’ll likely be using planer boards and downriggers to fish up to six lines with his hand-tied flies on the surface and up to six lines running plugs deep.

He said he landed and released at least a dozen rainbows larger than 20 pounds last fall, and inadvertently hooked an 18-pound lake trout in November that won the LPOIC Mack of the Month prize.

The rainbows are difficult to monitor, Dux said, so information researchers get from radio tagging is boosted with data obtained from anglers such as Roslak who keep log books and clip fins for aging the fish and determining growth rates.

Intensive research was involved in setting the actions that led to the lake’s kokanee recovery. Meanwhile, the research and fisheries programs continue to contend with old issues and recent ones, such as walleye, the newest invasive predator to show up in the lake.

Avista, through its Clark Fork Dam relicensing program, as well as the Bonneville Power Administration which manages Albeni Falls Dam, are the main funding sources for the lake’s fisheries programs.

“Avista spends about $750,000 a year on predator control,” Roslak said.

The dam managers provide roughly $2 million a year for fish-related programs, Dux said.

“In addition to the funding, the Avista team that works on dam mitigation takes great pride in preserving the lake environment and improving the fishery,” Roslak said.

Researchers have a spectrum of projects and studies underway on the lake, including tagging and radio tracking walleye and rainbows, gillnetting and fishing programs to suppress lake trout, kokanee spawning projects and surveys to monitor kokanee and their food supply.

“Since we started suppressing lake trout in 2006 the population has been reduced by more than 90%,” Dux said.

While invasive predators, including lake trout, northern pike and walleye, are threats to kokanee and trophy rainbows, each of the fisheries has advocates.

“Everybody has their favorite fish,” Roslak said. “I’m from the Midwest and I love to eat walleye. But walleye, pike and lake trout are very disruptive in the Lake Pend Oreille ecosystem.”

Some people don’t care about all the years and money devoted to establishing and maintaining the lake’s kokanee, native bull trout and trophy Gerrard rainbow fishery, he said. Heated discussions over priorities have long been common in Lake Pend Oreille fisheries management meetings, he said.

“The bottom line is this,” Roslak said. “You can fish for walleye and pike a lot of places. How many places in the world can you go and catch a 25-pound rainbow? Most people would have to travel, but we have them in our backyard.”

LPOIC members founded the 25-Pound Club in 1976. You can’t buy your way into it. You have to catch a rainbow that weighs 25 pounds or more to get a coveted patch that commemorates the moment.

“Countless 10-, 15- and 20-pounders are caught before an angler is likely to hook up with a patch fish,” Roslak said.

In the early 1990s, more than 20 patches a year were being awarded to anglers. By the mid-1990s the kokanee crash was happening and virtually no patches were earned as the food source for the trophy rainbows diminished.

The first 25-pounder in a dozen years was caught in 2013 as the kokanee recovery picked up. In 2020, six patches were earned, including one rainbow over 27 pounds.

Scientific approach

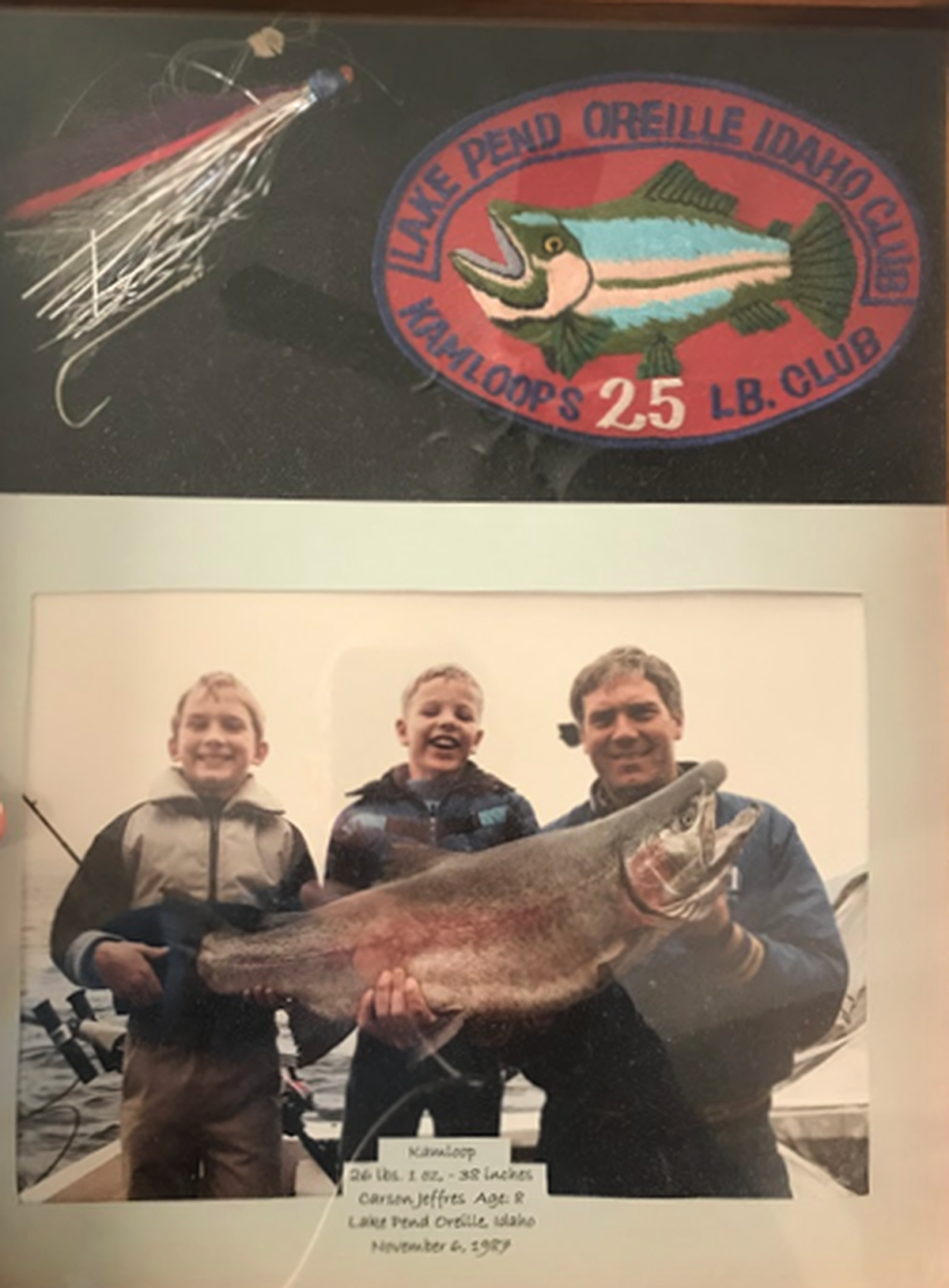

Sandpoint native Carson Jeffres got an early introduction to fishing fame in 1989 when he landed a 26-pound rainbow. He was 8 years old and fishing on Dave Devries’ boat with Dave’s son Thys while Jeffres’ dad was out of town.

“What I remember most is the first sight of the fish as it was coming up near the boat,” Jeffres said last week in a telephone interview. “It came in fairly easy at first and none of us thought it was very big. Then we saw it at the same time it saw us and Dave yelled, ‘Oh no!’ as the chaos began. Eventually, we got it in the boat.”

They motored directly to Kilroy Bay, where the fish was documented: 36 inches long and 26.1 pounds.

“It was a pretty big deal,” Jeffres recalled. “Everybody was excited.”

Despite his mom’s reluctance to part with the money for taxidermy, the family priorities were adjusted for the moment and they had the trophy mounted.

They framed the photo of Carson, Thys and Dave on the boat with the fish along with the red-and-silver fly that duped the rainbow and the coveted 25-Pound Club patch awarded by LPOIC.

Jeffres, a fisheries researcher at the University of California Davis, returns every year to fish Lake Pend Oreille with family and friends.

“Ten years ago, we were fishing just to hang out together,” he said. “Now we go out and catch big fish.”

Jeffres said he was a teenager when the fishery collapsed and didn’t understand the cause.

“Not until I got into fisheries did I start reading about Lake Pend Oreille in the scientific literature regarding the introduction of mysis shrimp, the increase in predation and the fall of kokanee,” he said.

“Lake Pend Oreille was used as an example of when introductions go wrong. Now it’s an example of when management goes right.

“I know that (Idaho Fish and Game) took a lot of blowback when they set a bounty for rainbows and lake trout to start the kokanee comeback. But the tough decisions were based on science that led to positive outcomes – a resurgence of kokanee, the rebound of rainbows and more people out fishing.”