‘Coerced’ murder confession complicates case against one Bonners Ferry chiropractor accused of killing another

Bonners Ferry is photographed on Wednesday, March 3, 2021. Bonners Ferry chiropractor Daniel Moore is accused of killing fellow chiropractor Brian Drake on March 12, 2020. (Kathy Plonka/The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

BONNERS FERRY – The blinds were closed, Marty Ryan wrote, but he still had a “broken view” through them, into the chiropractic exam room where Brian Drake lay dead on the floor from a single gunshot to the back.

Ryan, the assistant chief of the Bonners Ferry Police Department, was peering through the blinds, aided by a light on inside, soon after two calls came almost simultaneously into the Boundary County dispatch center to report what had happened just before 7:30 p.m. on March 12, 2020.

The first call was from a man who had heard a gun go off and had seen a man dressed in a hood and dark clothing leaving the scene, court records say.

The second call was the victim’s wife, Jennifer Drake, who told police she’d been on the phone with her husband when he said something bizarre: Someone had just shot him through the window. When her husband stopped responding, court records say, she hung up and dialed 911.

Responding officers kicked down the locked door of Drake’s office, where they found a single bullet hole through the double-pane glass and the closed blinds of his exam room.

Ryan and other officers worked through that first night of the investigation, but their work was just beginning.

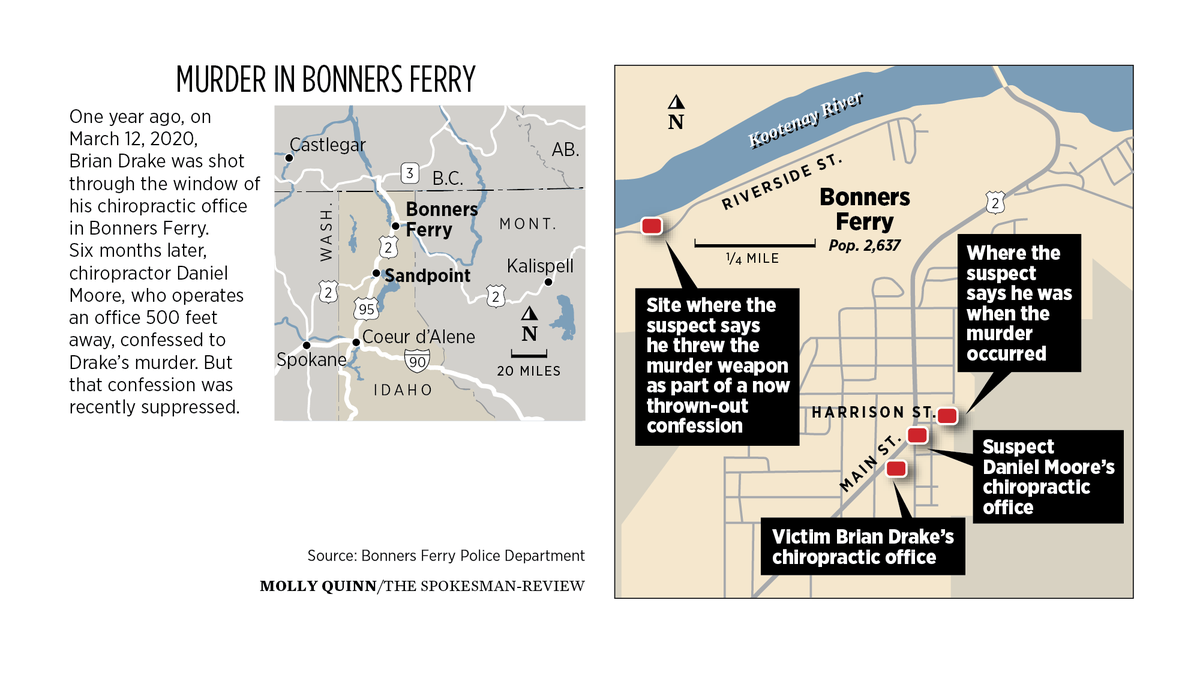

Six months later, law enforcement believed they had found the killer: Daniel Moore, a fellow chiropractor whose office was on the same side of South Main Street and about 500 feet to the north of the little clinic where Drake worked two days a week.

Moore, who had been practicing in town for 23 years, reluctantly confessed to the crime during an August interview, after asking repeatedly for a lawyer who was not provided, and told investigators he had inadvertently killed Drake while trying to scare him by firing a gun through his window.

His motive, he told police, was that Drake, who practiced in Sandpoint and Hayden the other three days of the week, had taken some of his patients. Investigators determined “over thirty” of Drake’s patients “had seen Dr. Moore in the past,” court documents say, though Moore’s attorney disputes this claim.

Moore also went with law enforcement officers to the banks of the nearby Kootenai River and threw a rock into the water to show them where he supposedly got rid of the murder weapon.

The 63-year-old with no prior criminal history, his attorney said – not even a speeding ticket, according to local court records – was jailed on $1 million bond and charged with second-degree murder.

But the prosecution of Moore fell into doubt last month when a judge ruled that Moore’s rights were violated, that his confession was coerced and that his admission of guilt – and everything that followed in his interview with investigators – should be thrown out.

Meanwhile, Moore’s defense attorney has raised a whole host of accusations, insinuations and uncertainties about how the case has been handled – and about who may have had a motive to see Drake dead.

An initial suspect

The night of Drake’s murder, Bonners Ferry police and Boundary County Sheriff’s deputies weren’t without leads.

First, there was the eyewitness who’d called to report what he’d seen from his apartment, across what’s both South Main Street and U.S. Highway 95 in Bonners Ferry.

After hearing the gun go off, he told the dispatcher he’d called out to the person who fled and that the person looked back at him before running off down Main Street.

He later told Ryan, the assistant chief, that the suspect appeared to be of Indian or Middle Eastern descent. He also described a “suspicious vehicle” that looked like a “’90s Malibu” and was seen in the area before and after the shooting occurred.

The witness jumped in his car to follow the suspicious person, who was on foot, he told 911. But when he couldn’t track down the person, he returned home to report what he’d seen.

That witness’s girlfriend told police she’d seen many of the same things.

With that information, Ryan went in search of surveillance footage.

He found a trove of it – and what it showed seemed to confirm what the witnesses had told police: A suspicious person in a black hood was in the vicinity of the crime scene at the time of the crime, court records say.

The suspect could be seen leaving the Kootenai River Inn near downtown Bonners Ferry before appearing to intentionally avoid security cameras, walking along South Main Street and returning to the inn, all around the time of the killing.

Police identified the suspect, and when the first witness’s girlfriend glimpsed a photo of the man, she “exclaimed” that it was the person she had seen “fleeing from” the crime scene, court records say.

The evidence was compelling enough for a judge to sign off on a series of search warrants that allowed investigators to comb through the suspect’s hotel room, truck and personal possessions, including his phone.

But after completing their initial investigation, law enforcement determined the suspect, who was visiting Bonners Ferry, wasn’t involved in the shooting for reasons that aren’t explained in court records.

Evidence

With that initial suspect crossed off their list, investigators examined other evidence, obtained surveillance footage from 18 local businesses and conducted more than 200 interviews, according to Idaho State Police Det. Sgt. Michael Van Leuven’s Aug. 28 affidavit.

At that time, half a year after the killing occurred, Van Leuven wrote, “several persons of interest have been looked at and alibis established.”

Ultimately, though, Van Leuven and his fellow investigators homed in on Moore.

Suspicions about Moore apparently derived from a few strands of circumstantial evidence.

The first mentioned in Van Leuven’s affidavit was a gas leak at Moore’s chiropractic office on March 15, three days after Drake’s murder.

According to Van Leuven’s affidavit, Moore’s close friend – and Boundary County coroner – Mick Mellett saw Moore’s vehicle parked at his office that Sunday morning, thought it was odd, went inside to see what was up, smelled a “strong gas odor indicating a gas leak” and found his friend “woozy” and getting up from an exam table.

Mellett brought Moore outside, reported the leak and helped him get to the hospital for treatment.

Later, Moore explained what had happened to Mellett, saying he’d “been changing a furnace filter, felt woozy and laid down,” Van Leuven’s affidavit says.

But investigators had doubts about that innocuous account.

An Avista gas expert who responded to the gas leak said it was his “opinion that the gas fitting was intentionally loosened,” while the Bonners Ferry fire chief reportedly thought the fitting was loose in a way that “was very odd,” the affidavit states.

When Moore was asked how he failed to smell the gas, he reportedly told investigators he’d lost his sense of smell as a child, when his nose was cauterized to prevent bleeding.

Mellett, the coroner, told Van Leuven he didn’t think Moore was attempting suicide, didn’t think he had anything to with Drake’s death and “didn’t think Dr. Moore had ever met Dr. Drake,” court documents say.

But investigators weren’t buying it.

Another reason to believe Moore killed Drake, according to Van Leuven, was a claim from an unnamed police source who had been a patient of Drake’s.

That patient reportedly told investigators that, about a year before his murder, Drake “appeared upset and when asked what was wrong he had said ‘he doesn’t want me up here’ or ‘they don’t want me up here.’”

While the affidavit doesn’t elaborate about to whom or what these statements might refer, Van Leuven also wrote that patient files indicated more than 30 of Drake’s patients had seen Moore previously.

Key to investigators’ suspicion was surveillance footage that apparently captured Moore’s truck driving around the proximity of the crime scene.

But Van Leuven acknowledged there was an issue with the footage: “Not all time stamps are accurate.” And there was another complicating factor: “The footage in some of the clips cannot individually be used to identify Dr. Moore’s (truck).”

The affidavit’s author claims, though, that “by linking one video to the next in the sequence, each video validates the other.”

What that sequence shows, according to Van Leuven, is Moore leaving Mellett’s house “just prior to the shooting,” circling the area, stopping briefly near the window through which Drake was shot and parking at his own nearby office.

“A human figure is then seen walking from the direction of Dr. Moore’s office toward Dr. Drake’s office one and a half minutes before the shooting occurs,” Van Leuven wrote. “A human figure is then seen walking (toward) and then back from the area of Dr. Drake’s office toward Dr. Moore’s office one and (a) half minutes after the shooting.”

Soon after, Moore’s truck is seen driving back to Mellett’s house.

When questioned by police, Moore told them he was at Mellett’s home for much of the night of the murder. In fact, Moore said, he was “with Mellett when the call came in about the shooting,” which Mellett responded to in his official capacity, assisting at the crime scene.

But investigators suggested there was a hole in Moore’s alibi.

When Van Leuven asked him if he was at Mellett’s house at 7 p.m., about a half-hour before the killing, Moore said he “didn’t know because he later became ill with kidney stones and had diarrhea and left Mellett’s house to go to his office to look for medicine. …”

Mellett, however, was certain Moore was with him at the time of the shooting, according to Van Leuven’s affidavit.

“Mellett said Dr. Moore arrived at his house no later than 6:15 p.m. and did not leave until after he heard about the shooting on his pager,” Van Leuven wrote. “Mellett said he was very sure about the times.”

Even when “pressed … about giving Dr. Moore an alibi,” Van Leuven wrote, Mellett said he was “absolutely positive.”

“Mellett’s demeanor throughout the interview was calm and relaxed,” Van Leuven wrote. “His answers seemed genuine and logical.”

A confession

With that information in hand and warrants being served on a number of his properties, investigators asked Moore to visit the Boundary County Sheriff’s Office Annex on Aug. 27 and to bring with him a small-caliber gun he’d bought for his wife.

Police knew that gun wasn’t the murder weapon, but soon after Moore handed it over, investigators took him to what they called a “secure area,” where Van Leuven told Moore they suspected he’d killed Drake.

Moore denied the accusation, but Van Leuven again told Moore he was the person responsible and asked him to explain his intent.

“Well, I didn’t shoot him and I’m sorry but that’s what it is,” Moore replied, “so I guess if you’re going to do that I need to get an attorney.”

At that, Van Leuven and another ISP detective closed their notebooks. Van Leuven then told Moore he was “going to terminate this interview” and left the room with his fellow ISP officer.

He later testified that he did so because it “sounded to me like he asked for a lawyer.”

But over the next 45 minutes, court records say, while Moore remained in the secure area, Van Leuven replayed the interview and spoke with other officers, including Ryan, the local assistant police chief, about Moore’s request for an attorney.

Ultimately, they decided Moore’s statement “was not clear” and decided to continue interviewing him without providing him an attorney, court records say.

This time, though, Ryan questioned Moore.

Ryan appealed to their shared community connections and raised the possibility the shooting wasn’t intentional.

In response, Moore continued to insist he was not only innocent, but that he didn’t even know Drake.

And he explained his presence on security footage around the time of shooting with an unusual story: He had a “stomach ache” and was unable to find a bathroom, so “he parked in the alleyway adjacent to Drake’s office and defecated in the alley, just as the shooting was occurring,” court documents say.

Ryan expressed disbelief and continued to press him.

In response, Moore said, “I need to talk to an attorney then.”

When that request went unheeded, Moore continued to ask for an attorney – “I think I need to talk to an attorney”; “I want to be able to talk to somebody who can give me my legal rights” – but Ryan continued to appeal for Moore to be honest and confess, lest law enforcement conclude the killing was premeditated.

Finally, one hour, 40 minutes after his interview with police began, Moore told Ryan he had killed Drake.

In a report Ryan filed the day after his interview with Moore, the assistant chief acknowledged Moore was “reluctant at first” but ultimately gave a detailed, if somewhat uncertain, account of how he killed Drake – and why.

Moore described loading a revolver, though he couldn’t recall its make or model. He described firing the gun from outside the window of Drake’s office, though he suggested he couldn’t actually see the victim and “did not actually know Drake was sitting on the other side of the window,” according to Ryan’s report.

When asked why he did it, Moore told Ryan he wanted to “scare” Drake.

“He thought having a shot fired at him would encourage him (Drake) to close down his office and move away,” Ryan wrote. “Moore rambled a bit about how Drake had several offices and, in a manner, did not need to be here in Bonners Ferry.”

Early the next morning, Moore said, he drove to a boat ramp and threw the gun in the Kootenai River.

He also said, a few days later, he staged a gas leak “with the intent of committing suicide.”

Casting doubt

But the gun Moore said he threw in the river has never been found, and Moore’s lawyer, a former federal prosecutor named Jill Bolton, has argued the investigation and prosecution of her client have been badly flawed.

Immediately after taking the case, Bolton reproached investigators for what she called her client’s “alleged ‘confession,’ ” which she said was “made after a prolonged custodial interrogation conducted in circumstances which violated Dr. Moore’s constitutional rights, including questioning him after he asked for counsel and subjecting him to custodial interrogation without having first read him his Miranda rights.”

She also requested Moore temporarily be released to receive an evaluation due to a “head injury which rendered him unconscious” the night before his “coerced and false confession.”

That request was granted, but two weeks later, Bolton blasted Boundary County chief deputy prosecutor Tevis Hull in court filings.

“(T)he state has failed to supply not only the most obvious material necessary to the preparation of the defense in this matter, but significant amounts of exculpatory material the State knows exists which implicates other suspects in the commission of the crime exculpates Dr. Moore,” Bolton wrote.

Among the materials not provided, according to Bolton, were such fundamental pieces of evidence as a recording of Moore’s confession, search warrants, witness statements and investigative reports.

She said the “remarkably deficient” sharing of evidence “indicates at best complacency” and “at worst, an effort to obstruct the delivery of this important evidence.”

She also began to question the strength of the evidence against her client, even alluding to “potential law enforcement perjury.”

Bolton argued the “assortment of private security camera footage suggesting Dr. Moore’s” truck was near the murder scene was “hardly noteworthy,” considering his clinic was also in the vicinity of the murder scene.

As for the timing of the footage, which police placed just before and after Drake’s killing, Bolton argued it was “uncertain, as the timestamps on the various video analyzed are mutually inconsistent. …”

“An additional deficiency in the State’s evidence,” Bolton wrote, “is their inability to identify Dr. Moore personally in any of the footage.”

The two eyewitnesses interviewed by police also couldn’t finger Moore. According to Van Leuven’s own Aug. 28 affidavit, they were “shown several photographic lineups, including one that contained a photo of suspect Moore, but did not identify any individual with certainty.”

Bolton also wrote that the investigation’s focus on camera footage “appears to have been conducted at the expense of inquiries into exculpatory evidence.”

Among that exculpatory evidence, Bolton said, was the original eye witness account of a hooded person who appeared to be “of Middle Eastern or Indian descent, qualities inconsistent with Dr. Moore’s physical appearance.”

There was also the other eye witness’s identification of a photograph of the original suspect as the person she’d seen fleeing the crime scene.

Beyond these doubts about the circumstantial evidence, Bolton argued the prosecution had presented no physical evidence linking Moore to Drake’s murder.

“Rather, the State of Idaho’s case against Dr. Moore rests almost exclusively upon the alleged confession obtained by law enforcement on August 27, 2020,” she wrote.

Bolton argued his “unconstitutionally procured ‘confession’ ” should be suppressed, “further diminishing the state’s evidence in their case against him.

“An additional factor indicating the weakness of the State’s case against Dr. Moore,” Bolton wrote, “is investigating law enforcement’s apparent willingness to commit perjury to secure a conviction.”

According to Bolton, this alleged perjury occurred when Van Leuven left out the evidence that undermined the case against Moore in his affidavit for a search warrant of Moore’s property.

“Law enforcement’s willingness to omit exculpatory information from an affidavit sufficient to render the resulting warrant invalid suggests that this was investigated with a degree of unprofessionalism and disregard for the requirements of the law that render additional constitutional violations likely,” Bolton wrote.

In an emailed response to a request for comment about Bolton’s criticisms of the investigation, Bonners Ferry Police Chief Brian Zimmerman wrote, “I would love to unload many frustrations but anything relating to the Drake case has to come from the Prosecutor’s office at this point. I couldn’t be more thrilled with Ryan’s performance here at the PD.”

“Since the case is still under investigation,” Zimmerman continued, “I can’t comment on anything about it until it is over but just because Jill Bolton raised questions about anything, doesn’t make it fact. She is just doing her job.”

Multiple attempts to reach Hull, the prosecutor, for comment were unsuccessful.

‘Police coercion’

In a ruling last month, District Court Judge Barbara Buchanan gave credence to Bolton’s complaints about how investigators – and Ryan in particular – handled their questioning of Moore.

In a February ruling, Buchanan criticized what she described as Ryan’s “pattern of badgering and overreaching.”

Buchanan wrote that even the request for Moore to come to the Boundary County Sheriff’s Office Annex on Aug. 27 was based on a “ruse,” as investigators asked him to come right away with a gun that they already knew wasn’t involved in the killing.

And she faulted Ryan for “feign(ing) ignorance” about Moore’s repeated requests for an attorney.

“Also, throughout the course of the interview,” Buchanan wrote, “police not only work to convince Moore that he has not made a clear request for an attorney, they also repeatedly tell him that if he does not confess, they will infer premeditation on his part and he will be booked for first degree murder.”

“The Court further finds,” Buchanan added, “that Moore’s subsequent confession was not voluntary, but rather, was the product of police coercion.”

And “because the police violated Moore’s due process rights by eliciting a confession by engaging in coercive police conduct,” Buchanan threw out “any and all incriminating statements made by Moore” after his initial request for a lawyer.

Prosecutors asked the court to reconsider its decision in court filings last week.

Claims and counterclaims

With the confession suppressed and a potential murder weapon still unidentified, Moore’s attorney is adamant about her client’s innocence and confident he will go free.

“I think the state has a very weak case, and I was quite surprised that they brought it in the first place,” Bolton told The Spokesman-Review.

“I can’t imagine that they would proceed on the evidence – or lack thereof – that they have presently,” she said.

She argues the motive attributed to Moore for Drake’s killings is “ridiculous and preposterous,” as his chiropractic business was “doing quite well.”

And she says his truck’s presence on surveillance near the crime scene is “pretty irrelevant,” as there were “hundreds of vehicles” captured on footage.

As for the idea that her client attempted suicide, Bolton said it’s “complete nonsense” and that the staff at Moore’s office was also “suffering from headaches and the smell of gas” at the time.

But Bolton hasn’t just argued that her client didn’t do the crime.

She has also suggested other people may have had motives to kill Brian Drake – and that investigative shortcomings mean the real killer is free.

“What is glaring about what they’ve disclosed is what they haven’t looked into,” Bolton said.

When Jennifer Drake sued Daniel Moore and his wife for wrongful death in her husband’s killing, Bolton responded with a counterclaim that implicated Jennifer Drake in her own husband’s death.

The counterclaim reads, “At the time of Brian Drake’s death, as Plaintiff (Jennifer Drake) well knew, there were multiple people, including herself, with a motive to kill Brian Drake, yet Plaintiff persisted for her financial, pecuniary and other selfish motives to create a publicly false persona of herself and her late husband.”

Bolton’s filing goes on to claim that Jennifer Drake obtained a “million-dollar life insurance policy … prior to Brian Drake’s murder, payable to her upon his death.”

Rather than a “good Christian and family man,” the counterclaims states, “Brian Drake was a philanderer, addicted to pornography and had sexually abused her (Jennifer Drake) and other women.”

Among those abused, according to the counterclaim, were Drake’s “own patients.” He also “engaged in sexually inappropriate behavior with members of his professional staff with whom he worked and likely had extra-marital affairs,” the filing states.

In response, Jennifer Drake’s attorneys called the allegations in Bolton’s counterclaims “libelous, fabricated and malicious falsifications of truth” and accused Moore of making them in a “cowardly” attempt to “humiliate and shame Jennifer Drake and her children and cause further emotional harm to a grieving family.”

They also asked Judge Buchanan to seal Bolton’s counterclaim.

Buchanan agreed, but not before allegations from the original claim were reported in local news publications. Buchanan argued it contains “highly intimate facts or statements” that “would be highly objectionable to a reasonable person,” that “might be libelous,” and that may lead to financial insecurity for the Drake family. Ultimately, Buchanan allowed the counterclaim to be kept public in the court record, albeit with all of the claims about Drake and his wife redacted.

Asked whether she stood behind the now-redacted elements of the counterclaim, Bolton said, “There wouldn’t be anything I would file in court if I didn’t have the factual basis to support it.”

‘Whodunnit’ theory

Seated with a friend in the corner of a Coeur d’Alene coffee shop on a recent morning and occasionally tearing up, Jennifer Drake remembered her husband as a “gentle soul” who taught their children guitar and coached their soccer teams.

“He was a very kind and honorable man,” said the 46-year-old mother of four. “God took his flaws and his failures, and turned it into a great story of grace. He was my children’s hero. He still is my children’s hero.”

The family spent about a decade in Austin, Texas, she said, before deciding to “get out of the big city” and move closer to Jennifer’s family and to the mountains in 2012.

Two years after arriving in North Idaho, in 2014, she recalled, her husband struck out on his own, opening his office in Bonners Ferry, where he initially worked just one day a week.

As business increased, he added a second day in Bonners Ferry and also opened offices in Sandpoint and Hayden, where the family lives.

Over those six years practicing in Bonners Ferry, Jennifer Drake said she never heard her husband mention Moore, who posted $500,000 bail in October and who has returned to his clinic and his patients on South Main Street.

And she was adamant that her husband “did nothing wrong. He is completely innocent.”

Otherwise, though, she refrained from speaking further about her husband’s murder or the ongoing case against Moore.

Bolton, though, has sought to compel Jennifer Drake – and others involved in the case – to share more, under what’s known as Idaho Criminal Rule 17.

In January, she subpoenaed Ryan, Van Leuven, the Bonners Ferry Police Department and Idaho State Police to produce all records pertaining to the investigation of Brian Drake.

She also subpoenaed the Heart of the City Church in Coeur d’Alene seeking records pertaining to financial assistance to the Drakes, their family therapy and counseling sessions, complaints against the Drakes, and records of discussions related to “Dr. Drake’s pornography addiction, infidelity, alcoholism or his proclivity for sexual battery.”

Jennifer Drake, too, was subpoenaed to testify.

Earlier this month, her attorneys asked the court to quash that request, arguing it was “unreasonable and oppressive.”

“Digging through Jennifer Drake’s personal life to find a minuscule fraction of support for (Moore’s) baseless and defamatory ‘whodunnit’ theory and to point the finger at Jennifer is well outside the bounds of what Rule 17 allows,” her attorney wrote.

“The very purpose of subpoenaing the requested documents is to cause further harm and damage to Jennifer, to revictimize her, and to abuse the criminal justice process in the name of declaring Defendant Moore’s ‘innocence,’ ” Drake’s attorney continued.

The court is scheduled to consider the motion to quash the subpoena on March 31.

On the same day, it will consider the prosecutor’s request to reconsider the suppression of Moore’s confession, and the defense’s request to move the trial from Boundary County to Kootenai County.

Bonners Ferry is photographed on Wednesday, March 3, 2021. Bonners Ferry chiropractor Daniel Moore is accused of killing fellow chiropractor Brian Drake on March 12, 2020. (Kathy Plonka/The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo