Spokane City Council considers formal acknowledgment of Native American land

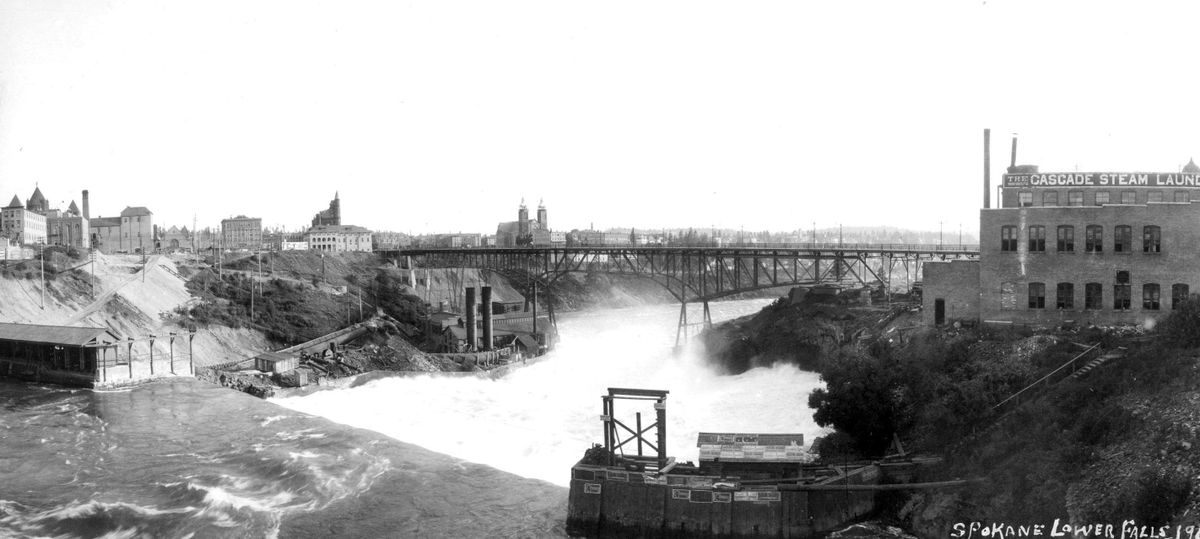

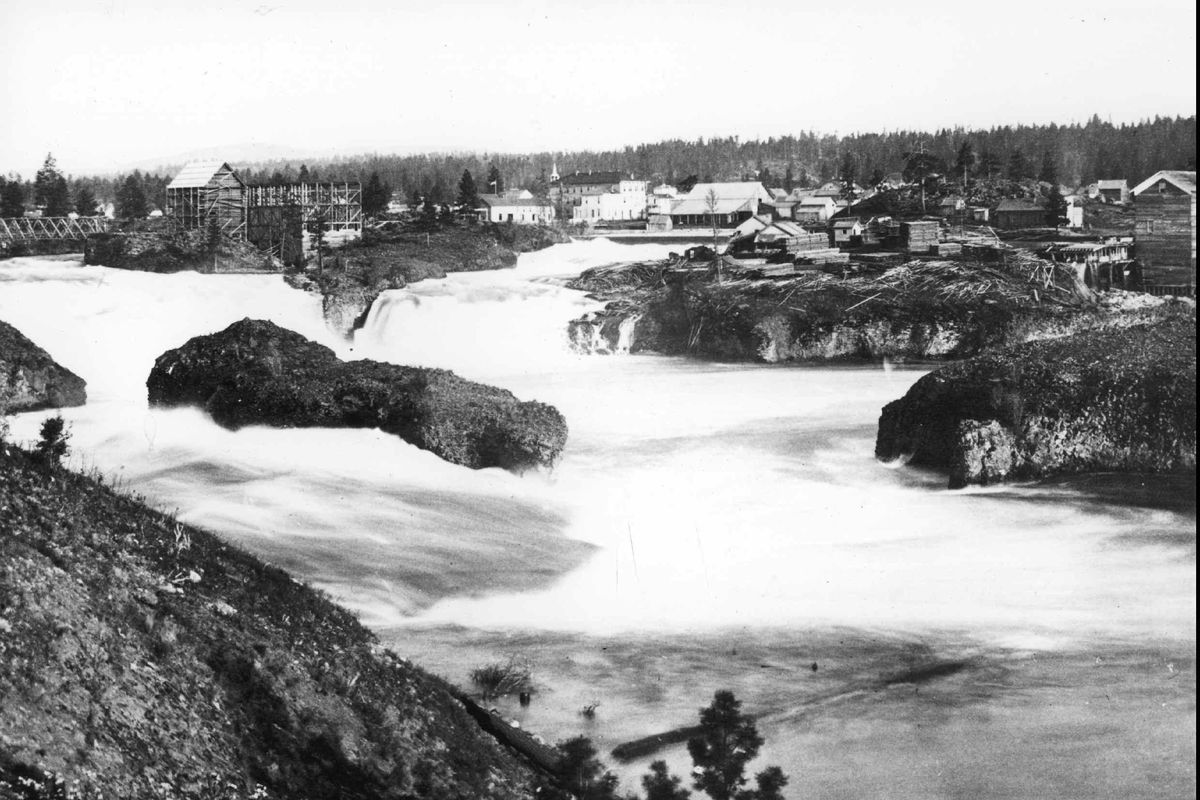

This is a 1907 photo of the Spokane River Lower Falls. View is looking to the west with downtown Spokane on the left. The Cascade Steam laundry is the prominent structure on the north bank of the river. Cascade was established in Spokane in 1890. (THE SPOKESMAN-REVIEW PHOTO ARCHIVE)Buy a print of this photo

Once the lifeblood of Indigenous people, the rushing waters of the nearby Spokane Falls are audible to anyone standing just outside the Spokane City Council’s chambers.

Now, city leaders and the Spokane Tribe are working to ensure its people are heard inside City Hall.

A proposed Spokane City Council resolution would formally recognize the history of harm perpetrated on the Spokane Tribe of Indians and aim to improve its ties with the city that sits upon its ancestral land.

The resolution would acknowledge that Spokane City Hall was built on the lands not ceded by the Spokane people and call for the appointment of a tribal liaison in City Hall.

The resolution, set to be taken up for a vote by the City Council in the coming weeks, is nonbinding. It would not create, fund or formally establish a new tribal liaison position but would endorse the concept of one.

The Spokane Tribal Business Council already has approved the land acknowledgment. Ultimately, the tribal leaders who helped draft the resolution say its efficacy will depend on whether its promises translate into policy.

“There is a call to action on that land acknowledgment, so it’s not ‘OK, we’re done, we’re in the past,’ ” said Jennifer Le- Bret, a tribal member who helped draft the resolution. “We have a future, how do we now build upon that?”

The river

Ancestors of the Spokane Tribe lived seminomadically across about 3 million acres of what is now Eastern Washington.

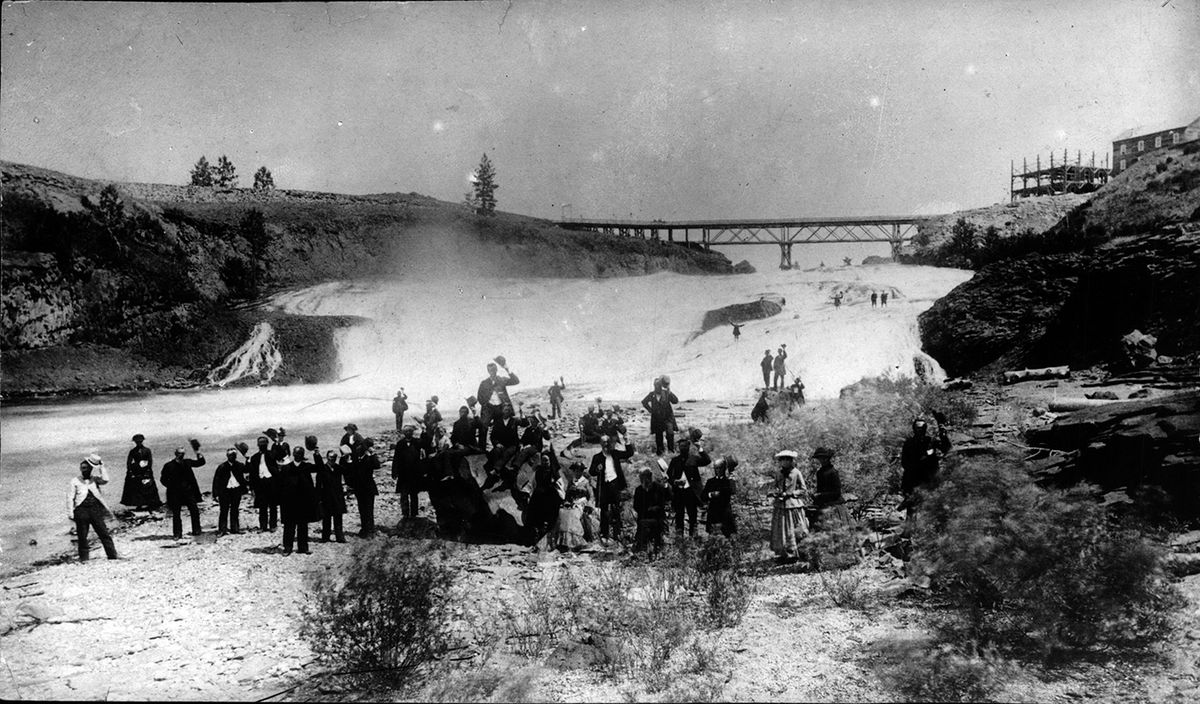

Central to the Spokane peoples’ culture, spirituality, diet and economy were the Spokane Falls, the effective end of the line for countless migrating salmon and a rich source of annual bounty.

The proposed land acknowledgment resolution notes that Spokane Falls and what is now Riverfront Park, which are effectively the backyard of City Hall, are traditional gathering places for the Spokane people and their guests, including the Coeur d’Alene, Kalispell, Colville and Nez Perce.

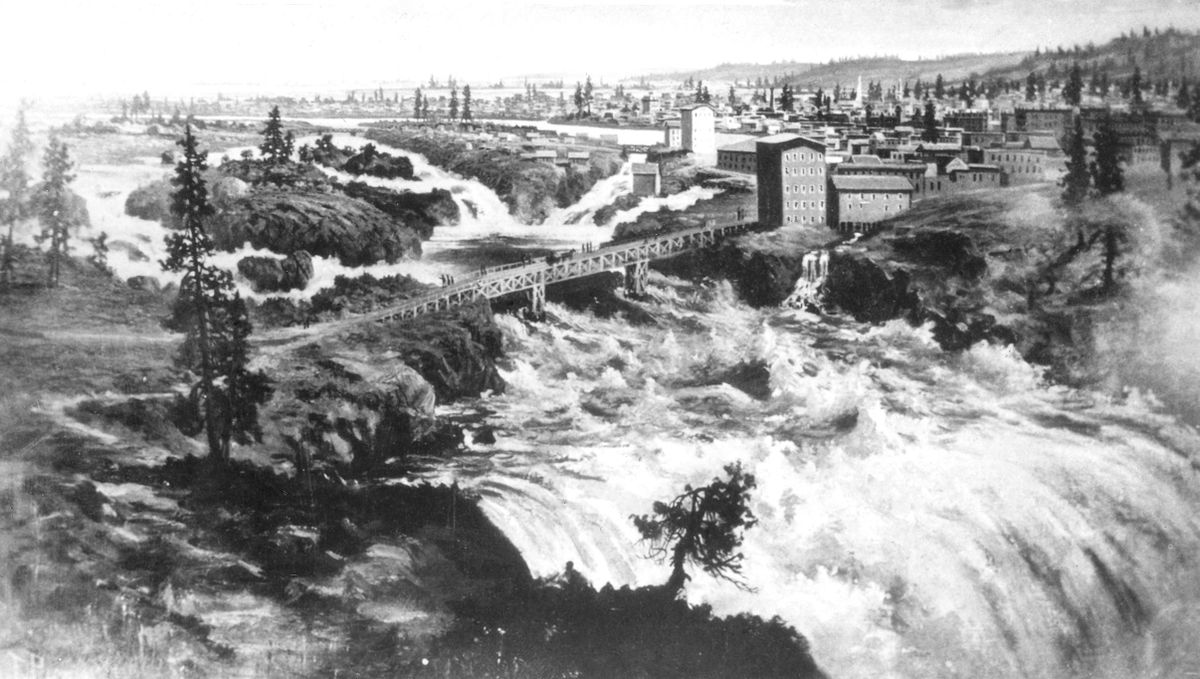

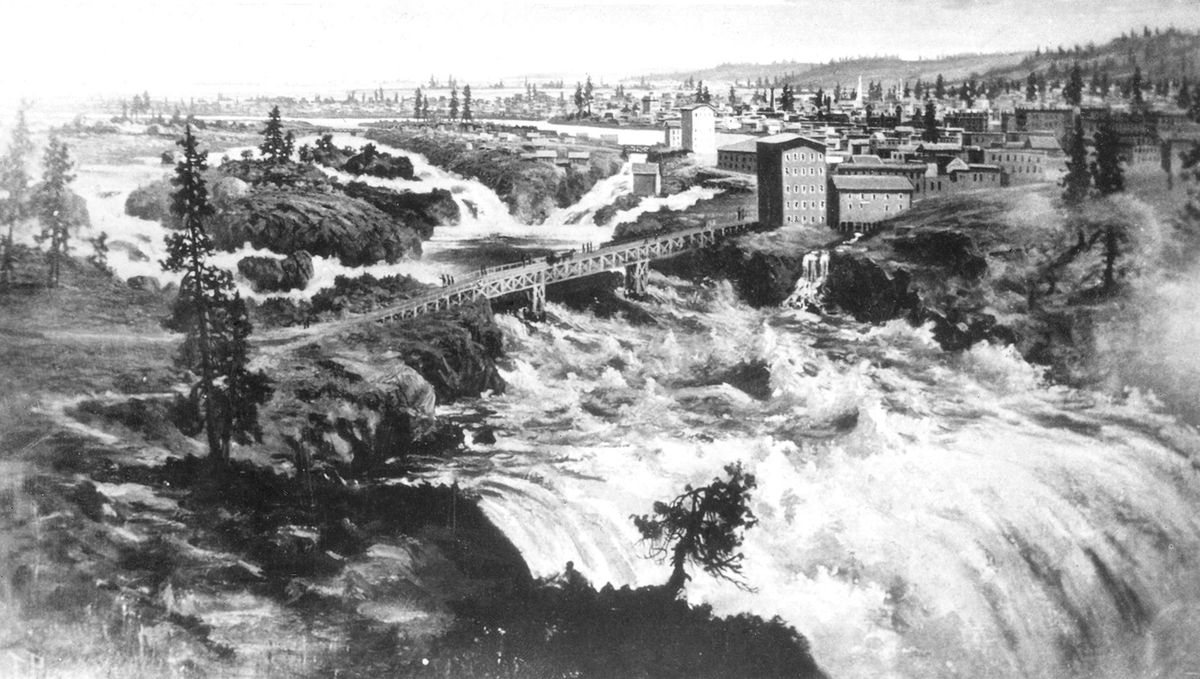

Spokane Falls, Spokane, Washington 1878 (THE SPOKESMAN-REVIEW PHOTO ARCHIVE)

Tribal historian Warren Seyler has worked to educate people on the bond between the river and Spokane Tribe, giving presentations around the area at places including Gonzaga University. It can be difficult to explain to a contemporary audience.

“Just watching their expressions and feedback, so many people don’t realize – they kind of assume that connection between the tribe and the river, but they don’t understand how deep it goes,” Seyler said.

What the buffalo was to Plains Indians, the river and salmon were to the Spokane people. They followed the leadership of Salmon Chiefs, who oversaw the harvest and distribution of fish.

The Spokane River was once so plentiful it ran black with fish, swimming so tightly together that it appeared one could walk atop them from one bank to the other.

The traditional belief is that humans were created at the same time as animals, and thus the fish are the brothers and sisters of people.

“Your culture, your traditions, all those things tie to what gives you life … there’s a true connection,” Seyler said.

The history

But the same forceful falls that fed Indigenous people enticed settlers to Spokane.

“For the non-Indians, they see the falls and the power it possesses – to turn the grist mills to grind the grains, the power for generating electricity – that was the attraction of the falls,” Seyler said.

In 1806, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark’s famous Corps of Discovery expedition passed through the area. In short time, the land was settled by white people, first via the Spokane House trading post in 1810 and later by the construction of Fort Spokane.

The following decades were marked by settlers’ continued encroachment into Spokane.

“As many as stars in the sky, they just kept coming,” said Margo Hill, a Spokane Tribal attorney and associate professor at Eastern Washington University.

Settlers in Spokane, the very name of which is adapted from the Salish language, “accelerated the removal and placement of local tribes on reservations, cutting tribes off from their cultural and traditional practices throughout the region,” the resolution states.

“It basically was our land,” said Marsha Wynecoop, a Spokane Tribal Language Program manager who helped develop the acknowledgment resolution. “We lived there for thousands and thousands of years, and it was pretty much just taken away.”

Seeking to quell conflict and secure land for the perpetually growing population of settlers, Territorial Gov. Isaac I. Stevens endeavored on what became known as the “Treaty Trail,” signing 10 treaties that dispossessed dozens of tribes in the span of little more than a year. In 1855, he proposed that the Spokane people agree to move to a reservation with the Nez Perce or Yakama tribes.

His treaty request was rejected outright, as it failed to recognize that the Spokane and Nez Perce did not always live in harmony.

“Our cultures weren’t the same; our traditions weren’t the same,” Seyler said.

Word traveled fast between tribes that Stevens could not be trusted and that settlers would not honor their treaties, Seyler said. The military had continued to arrive in greater numbers, along with surveyors. The Spokane people knew what that meant.

“The survey is the first thing they do before they take your land,” Seyler said.

In the spring of 1858, Native Americans were gathered near what is now Rosalia to harvest camas root when they were met by the forces of Col. E. J. Steptoe, which were en route to Fort Colville.

A battle ensued in which both sides lost lives, but warriors with the Spokane and other tribes sent Steptoe’s men retreating to Fort Walla Walla.

News of the conflict made its way back to Washington, D.C., and Col. George Wright was dispatched to avenge the loss.

“1858 is when we see Col. Wright get the troops together,” Hill said. “They were going to teach those Indians a lesson.”

With superior weaponry, Wright’s forces swept through the Native Americans at the Battle of Four Lakes, which took place between what is now Spokane and Cheney, and in the Battle of Spokane Plains later in 1858. The losses led to the signing of a peace treaty that allowed whites passage through tribal land, but did not cede it. The agreement effectively ended the Native Americans’ resistance in the area, while white settlement continued to flourish.

After decades of conflict between settlers and natives, the federal government created the 157,000-acre Spokane Tribal Reservation northwest of the city of Spokane in 1881.

The Spokane people were not monolithic and had several leaders. They were divided into three groups – the upper, lower and middle bands. The people who moved there were mostly of the lower band of Spokane people, who generally lived along the Spokane River closer to where it flows into the Columbia. Many in the middle and upper bands refused to leave the land at first. Ultimately, they signed an agreement in 1887 to cede their land, with many moving to the Coeur d’Alene, Flathead or Colville reservations, in addition to the Spokane reservation.

But establishment of the reservation was not the only tool to remove Native Americans.

The decades that followed Wright’s military campaign still were marked by both physical harm and what Seyler described as cultural genocide, particularly in the form of starvation.

In the late 19th century, canneries harvested millions of pounds of fish that were shipped and sold outside the Inland Northwest. The result was profits for settlers, but a diminished salmon population that cut Spokane people off from their source of food for thousands of years.

“Remove the fish, and you can control the Indians,” Seyler said.

Many people of the Spokane Tribe were later forced to relocate in the 20th century due to construction of the Grand Coulee Dam, which was ruinous for the salmon population they relied on and created reservoirs that flooded ancestral lands. The tribe was not compensated for that loss until the 2019 passage of the Spokane Reservation Equitable Compensation Act.

Spokane remained predominantly white because it was designed that way, Hill argues. The displacement of Native Americans was followed by policies like redlining and the use of racial covenants to ensure housing was available only to whites.

“My grandmothers knew and told stories about having to be on the far side of town at nightfall. Brown people were not welcome in the city of Spokane even though that was our own home and our own indigenous lands,” Hill said.

Spokane City Councilwoman Karen Stratton, whose grandmother was a Spokane Tribal member, recalled similar stories. Her grandmother never felt welcome in the city of Spokane, she said. Stratton’s mother, Lois Stratton, was born on the Spokane reservation to a Native American mother and white father. She eventually represented Spokane in the state Legislature.

As a boy, Seyler’s family would usually choose Chinese restaurants when dining out in the city. At the time, he thought they just enjoyed the cuisine. It was only when he was older that he realized Native Americans often weren’t served at white-owned establishments.

Education

Land acknowledgments like the one under consideration by the City Council are part of a broader education movement that is “just beginning,” Wynecoop said.

“Right now it’s finally being taught in the schools, the history of the Spokane people. It’s just barely reaching the surface right now,” Wynecoop said. “Maybe in a few more generations it will actually mean something.”

That history also rose to the surface recently when the City Council chose to rename Fort George Wright Drive after Whist-alks, a Spokane Indian who played a role in efforts against Wright in 1858.

“As we got closer and closer to getting the momentum up to change (Fort George Wright Drive) to Whistalks Way, I think we all felt this was an appropriate time, again, to stop and to acknowledge the tribal lands that we inhabit,” said Stratton, one of the land acknowledgment’s sponsors on the Spokane City Council. “Creating those partnerships, the tribal legacy and the history of Spokane was a good idea.”

But it’s not simply ancient history. The consequences of settlement continue to reverberate today.

Estimates vary, but the Spokane people depended on the river for at least 60% of their diet, Seyler said.

“You go from a completely natural diet for thousands of years and then you throw sugars at us, or other things that are foreign to our bodies – alcohol and those types of things that Europeans have been accustomed to for thousands of years – and people wonder why we have such high rates of diabetes, high rates of cancer?” Seyler said.

The resolution aims to do more than just acknowledge the history of the land and the Spokane peoples’ displacement. It also pledges to create a more substantive, lasting partnership between the Spokane Tribe and city leaders.

“Once a year, probably in April around Earth Day, we would read it out loud and invite the chair of the Spokane Tribe to give us a report on the state of the earth, land and water,” said Spokane City Council President Breean Beggs, one of the resolution’s sponsors.

Beggs suggested the council could also hear an annual report, around the time of Indigenous People’s Day, from representatives of the city’s urban Native American community.

The resolution’s long-term impact may depend on the city’s implementation of a liaison with that community.

“How that person is chosen is important to us,” LeBret said. “What is their background, what are their job requirements, what is their background and expertise … if you do have that position, there’s a lot of groundwork that needs to be done.”

Already, Beggs told The Spokesman-Review, the City Council is making it a habit to involve the tribe in discussions. The draft of a public infrastructure sustainability plan will be sent to tribal leaders for input, he said.

“We’re trying to just start making it a practice,” Beggs said.

Stratton suggested there are opportunities to more widely market the annual Gathering at the Falls Powwow in Riverfront Park. She’s also been in talks to establish a tribal village in Spokane that would not only provide housing for Native Americans, but also be a hub for arts and gathering.

“There’s a lot that we can do, as long as we move very, very thoughtfully and don’t roll all over tribal members because we think we know it all,” Stratton said.

As the city develops a climate change adaptation plan, Apolonio “Polo” Hernandez said it should consider incorporating the tribe’s wishes. Hernandez sits on the city’s sustainability action subcommittee.

“Reintroduction of salmon is something that’s being pushed,” Hernandez said. “What role can the city play as part of that conversation and how do they ally with tribal nations around us?”

Several tribal members pointed to their continued and disproportionate need for access to housing and jobs, as well as a renewed focus on environmental issues.

“It’s largely symbolic,” Hill said of the land acknowledgment. “It does mean something to recognize the settler, colonial brutality against the Indigenous people. But we’ve got work to do.”

Editor’s note: This story was changed on Monday, March 15, 2021. Because of a reporter error, an earlier version incorrectly stated that Apolonio “Polo” Hernandez is a Spokane tribal member.