Coeur d’Alene nonprofit worried about effects of minimum wage hike on disabled workers

A provision tucked into proposals to raise the federal minimum wage has Terri Johnson worried about the future of her workforce.

Tesh, Inc. in Coeur d’Alene is a nonprofit, multiservice rehabilitation facility for people with disabilities. One of those services is providing workers with physical and mental impairments the ability to work on contract, but for pay that doesn’t meet the minimum wage standard.

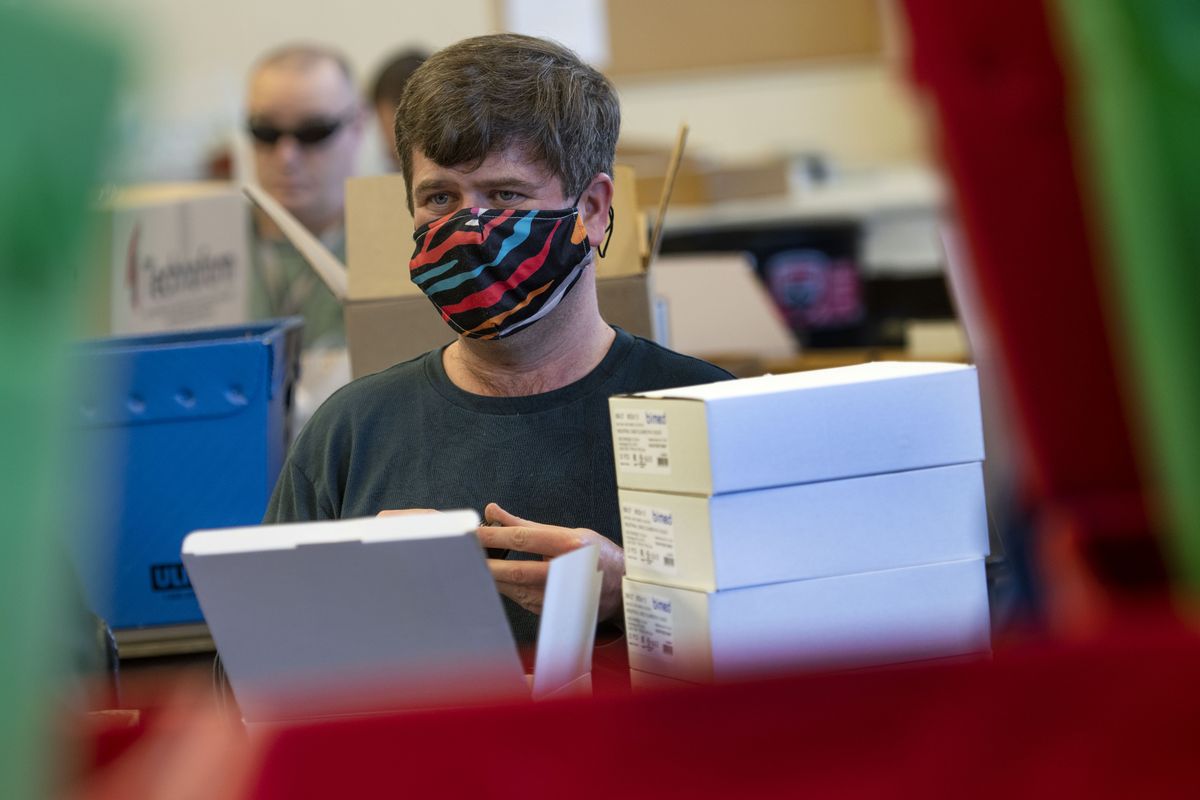

On a recent Thursday, several of the 19 workers currently being paid rates below minimum wage put together tree plugs, plastic devices used to inject substances into bark to deter hungry insects.

“They take so much pride in their work,” said Johnson, the nonprofit’s vice president. “But they couldn’t be out there doing things like vacuuming, or cleaning windows. But they can do this, and rock it.”

The exemption has been in place federally since the 1930s as part of the New Deal. It was originally intended as a way for people who wouldn’t otherwise find job opportunities to work in a sheltered environment that would give them a paycheck and perhaps the skills necessary to seek full employment. Tesh also provides encouragement and support for workers, and allows them to work in an environment that may be impossible to find outside their walls, Johnson said.

“For some of them, it’s not safe to be out in the community. Here, they’re safe, they’re supported,” Johnson said. “If there’s a struggle that they have, or something like that, then we support them.”

The provision has come under fire in recent years from disability advocate groups at both the state and federal level, with opponents saying the exemption is dated and doesn’t afford disabled workers the dignity of a livable wage. A September 2020 report from the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights called for the certificate program to be phased out.

The voices of those who derive a sense of worth from that paycheck, and the full trays of complete tree plugs, often don’t factor into the discussion, Johnson said.

“They don’t feel that our clients are being treated correctly, because they’re not making minimum wage. I think that’s where their hearts come from,” she said. “There’s a strong lobby of people who don’t have cognitive delays leading that charge.”

Among the workers assembling tree plugs was Terri Manning, who demonstrated the three-step process that is one of several tasks workers can complete for twice-monthly paychecks.

“I usually take it and go shopping for clothes,” Manning said.

“This place is for people who don’t have places to go, or don’t have jobs,” Manning added, pausing from her work assembling the plugs. “So they can come here, and they can have a job, doing tree plugs, or they can work on janitorial crew.”

Chris Bowen was assembling industrial cable glands nearby, devices used for junctions in telecommunications equipment. He also has a part-time job cleaning pool tables and the parking lot at a local bar and grill, and he works with a job coach.

Bowen teases when asked how long it took him to learn the assembly process.

“It took me, like 203 years,” he said, smiling beneath a mask.

Nearby, Blane Gilbreath, who has a traumatic brain injury that left him with impaired vision, among other symptoms, assembles the tree plugs via sound and touch, knocking the device on the table to ensure the pieces fit snugly. Gilbreath uses his money to order lunch at McDonald’s on trips into the community facilitated by the center, he said.

Both Manning and Bowen are compensated for their work based on a rate calculated by Howard Hogan, Tesh’s commercial services manager. Compensation is based on the productivity of a worker compared to someone who doesn’t have a disability. The payment rate for the tree plugs, for example, is based on how many the workers can complete in an hour compared to a standard of 414 established by a worker without a disability.

“We’ve had some amazing people, with some incredibly fine motor skills, and they will blow that out of the water,” Hogan said. “Then they get whatever they make. Most of the time, they’re not. The average productivity rate in my program is about 30%.”

State and federal legislation has been introduced that would either eliminate the certificates that allow such a calculation, or require the nonprofit to pay a minimum hourly wage, regardless of productivity. The federal Raise the Wage Act, which has received support from President Joe Biden, would prohibit the Labor Department from issuing new certificates for subminimum wages. For existing certificate holders, including Tesh and seven other entities in Idaho, hourly rates would need to be increased on a sliding scale to $15 per hour within four years of passage of the bill.

Johnson said that would mean ending the subminimum wage program at Tesh. Some workers could continue certain jobs, but the nonprofit bids for contracts, and their workers wouldn’t be competitive with alternatives.

“We’ve already talked about having to close this down,” she said.

Another federal proposal would simply do away with the certificate process, without changing the federal minimum wage. Backed by Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers, the bill would call for an increase in the wage rate as a percentage of the prevailing federal minimum wage over a six-year period. The bill would also create a grant program within the Department of Labor transitioning entities including Tesh from providing contract work to “providing competitive integrated employment” for those with disabilities.

“As America rebuilds from the health and economic crises created by the coronavirus, we must ensure people with disabilities aren’t left behind,” McMorris Rodgers said in a statement in September supporting the bill. The congresswoman intends to reintroduce the legislation in the new Congress, her office said Wednesday.

The federal minimum wage legislation includes a provision that would encourage referrals of such cases to federal and state agencies “with expertise in competitive integrated employment,” but does not create the grant program.

In Washington state, lawmakers have already stopped the practice of issuing such certificates to state agencies through legislation that took effect in July 2020. Lawmakers are now debating a bill that would end the issuance of such certificates in Washington by July 2023, a program that supported 673 subminimum wage jobs at 18 locations statewide as of January 2021, according to the U.S. Department of Labor.

Nationally, the program supports about 45,000 workers receiving subminimum wages.

The bill passed in the state Senate, and is now awaiting action in the House of Representatives, where it’s scheduled to receive a committee hearing Friday. Supporters say its approval is a civil rights issue, and ending the program is long overdue after the state established its certificate program in the late 1950s.

“Our subminimum wage law dates back to 1959,” said state Sen. Emily Randall, D-Bremerton, while introducing the legislation at a hearing in February. “It predates the Americans with Disabilities Act, and when it passed, schools could refuse to educate people with disabilities. Continuing to allow subminimum wage lets employers treat those with disabilities less than, and that is simply unjust.”

Frances Huffman, executive director of Tesh, acknowledges that some sheltered employment centers have been run incorrectly in the past, accepting clients that shouldn’t be there to work. But the legislation proposed at both the state and federal level appears driven by the belief that businesses would adapt to employing everyone at a set wage, even those with severe cognitive disabilities.

“My concern is for the few that are left, what option do they have if competitive employment doesn’t work out for them,” she said. “What options do they have?”