With gang violence on the rise, Spokane-area law enforcement leaders call for community action

The Spokane area is experiencing a variety of gang violence the county’s top law enforcement officials have never seen before.

“We’ve never had kids go, ‘I don’t care. I don’t care if I die and I don’t care if I kill you,’ ” said Spokane County Sheriff Ozzie Knezovich. “And that’s coming from the older generation of gangsters. They’re going, ‘These kids have no concept of empathy. They will kill you in a heartbeat.’”

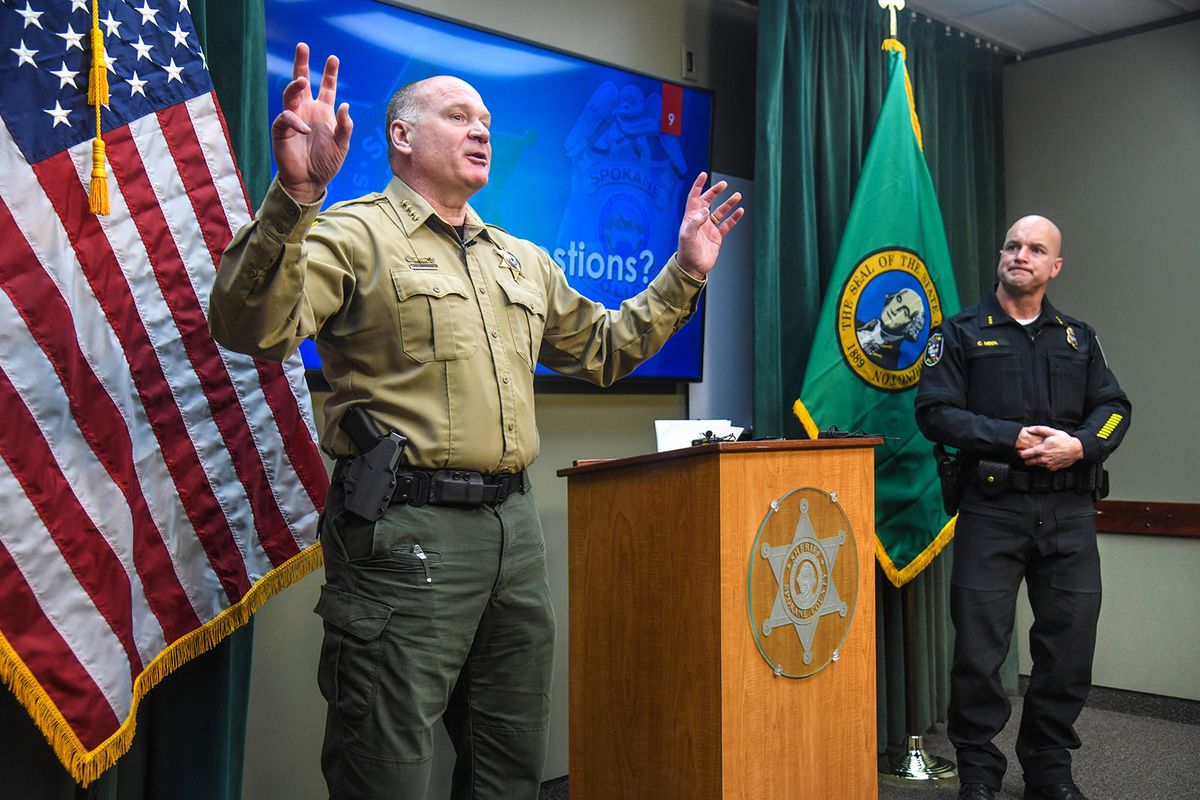

Knezovich and Spokane police Chief Craig Meidl held a news conference Monday to outline their concerns with the rise in gang violence this year throughout Spokane and Spokane County.

Year-to-date, there have been almost four times as many shootings and drive-bys recorded by the Spokane Police Department than there were at this point last year, Meidl said. Knezovich said youths embedded with gang activity ultimately face two outcomes: prison or death.

“If you’re looking at where we’re at year-to-date, our January and February is almost as high as our summer months,” Meidl said. “We’re very concerned about where we’re going, especially as we’re trying to work with these kids, and they are completely indifferent about their future.”

For that reason, law enforcement leaders are now calling on various sectors of the community – from the criminal justice system and parents, to witnesses and victims, to step up to stop this activity.

Meidl said law enforcement has historically dealt with witnesses and victims unwilling to come forward, as they fear retaliation or they wish to take care of these issues themselves.

“The chief and I both know that’s rough because there’s a certain amount of risk in stepping forward. That could be your door the next round comes through,” Knezovich said. “But how many of your kids are you going to let die before we put an end to this?”

‘They don’t care about killing people’

To illustrate their concerns, Knezovich and Meidl highlighted criminal activity between Jan. 1, 2020, and Feb, 27, 2021, involving 64 known gang members. Knezovich said there are gang connections in the area linked with groups from California – Stockton and Long Beach, in particular.

Of the 35 murders and manslaughters recorded throughout the county during that period, four (12.9%) were linked with juvenile gang activity. Of the 64 referenced individuals, 75% of them are under 21 years old.

Knezovich said the activity is not confined to one particular area.

“We’ve talked with some of the older gang members. They have made it very clear that these younger gang members are not playing by any kind of understanding or, let’s say there is such a thing, rules associated with this lifestyle,” he said. “They don’t care about killing people, and that is the bottom line.”

Many children have spent more time out of school and learning from home virtually over the past year since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Knezovich and Meidl, however, said they are unsure whether the rise in activity is related.

“I don’t know if having everybody back in school changes that dynamic,” Knezovich said, noting that other cities across the Pacific Northwest are having similar issues. “What happens on the street sooner or later shows up in school.”

Breaking the cycle

Calling on the community to break the cycle, Knezovich said the criminal justice system has to work better to intervene with juvenile perpetrators “before they commit the serious crime.”

“Maybe then we’ll have a chance,” the sheriff said, “but you can’t do that with a criminal justice system that does nothing other than let them back out on the street to repeat the crime with no accountability.”

While noting that programs – such as apprenticeships and other business partnerships – exist that can help get juveniles away from the gang lifestyle, Knezovich said more people from at-risk communities need to “join in.”

“We can create every program in the world,” he said, “but if you’re not getting your kids to those programs, nothing changes.”

Meidl encouraged parents who know or suspect that their child is hanging around bad crowds to steer them in the right direction – or ask for help from members of their community, such as church leaders, to get that message across.

Asked how parents can monitor their children’s online activity, Meidl suggested asking their children for the passwords to their online accounts. Citing studies involving teenage brain development, Meidl said “you can respect their privacy when they’re 18.”

“I can’t go to talk to a lot of these kids. I’m a white male police officer. I can’t talk with them, but there are people in that community who can,” Meidl said. “And it’s not just the minister. It’s other members of churches as well. We need them to come out of the woodwork and say, ‘What can I do to help?’ ”