Thanks to effort to vaccinate the homeless in Spokane, one man’s shot will open door to permanent housing

Jerry Thompson has spent the past month in respite care at the House of Charity, recovering from a below-the-knee amputation, his fourth surgery.

The COVID-19 vaccine is the key to his new apartment.

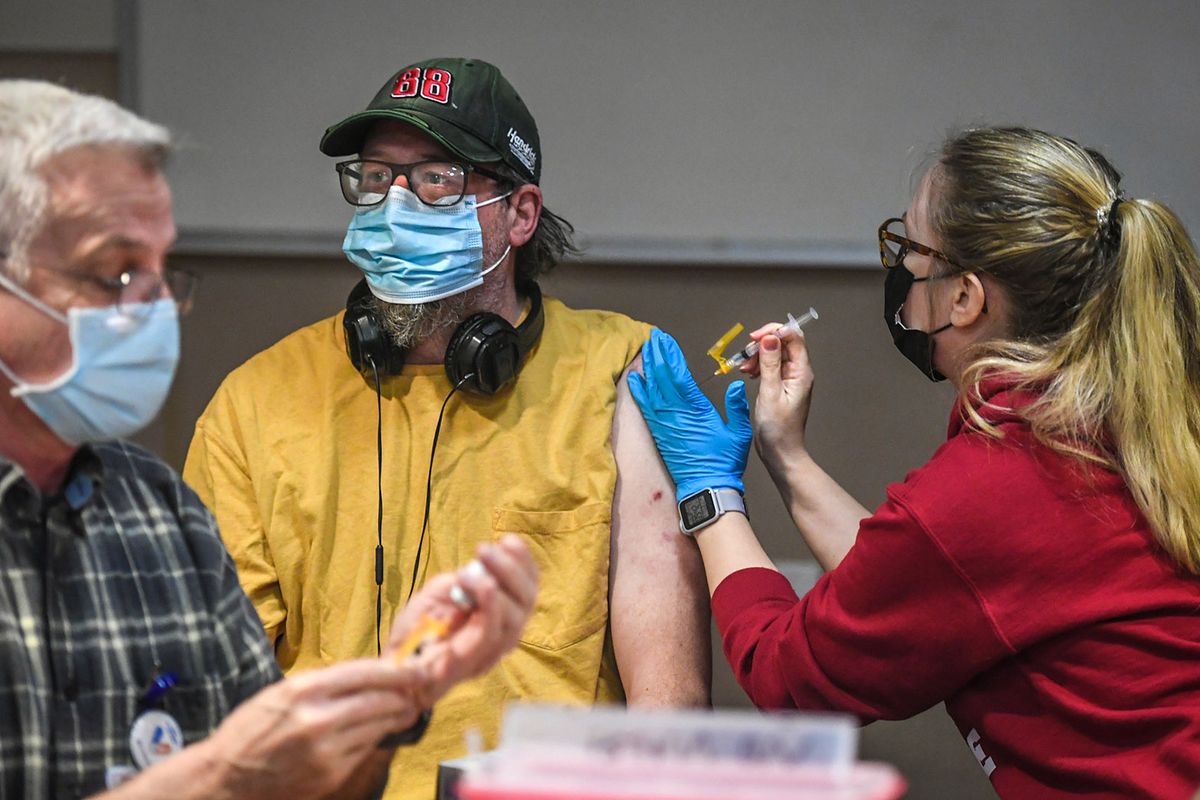

Thompson received his second and final dose of the vaccine during a clinic held at the homeless shelter by the Spokane Regional Health District on Tuesday.

Not only will the vaccine offer him protection from the coronavirus, it’s the last step before he moves into the Rose Pointe assisted living facility in Spokane Valley, which “wanted to wait until after I got vaccinated,” he said.

Now 56 and in a wheelchair, when Thompson moves into Rose Pointe it will be his first stable home since he was 12 years old.

“I’ve already got my stuff packed,” Thompson said.

The health district team wheeled up at the House of Charity on Tuesday with a cart of medical supplies and 70 doses of the COVID-19 vaccine.

It was the second of a three-day mobile vaccination effort the health district held this week at various shelters across Spokane.

The health district has reserved vaccine doses for a targeted effort to reduce the risk of COVID-19 in shelters and protect the community’s most vulnerable residents.

The district held clinics at several sites in late January and early February to provide first doses to 184 people. This week’s second-dose clinics were originally scheduled for last week, but wild winter weather across the country disrupted the supply of vaccines.

Although COVID-19 cases among the homeless have not reached the number and severity first feared when the pandemic hit last March, the disease has had an impact on shelters. Family Promise’s Open Doors had to collectively quarantine after an outbreak last year, while Union Gospel Mission’s men’s shelter had to stop accepting new guests after an outbreak earlier this year.

In accordance with state guidelines, vaccines were offered only to shelter residents who are at least 50 , because they effectively live in a multigenerational household. Staff members also were vaccinated if they were at least 65 years old or 50 or older living in a multigenerational household.

The number of people currently eligible in shelters was somewhat small and manageable for health district staff. They kept a spreadsheet of everyone who received a first dose and used it as a reference when making the rounds this week. They’ll know anyone who missed a second dose by the end of the week.

Vaccination efforts at homeless shelters are not new to the health district, which worked in recent years to combat a Hepatitis A outbreak, but the COVID-19 vaccine is unique. Only specific people are currently eligible and every dose has to be accounted for – once the vaccine is thawed, it can’t simply be placed back in cold storage for use another day.

Staffing the clinic on Tuesday were volunteers from the Medical Reserve Corps and the health district’s nursing school interns from Gonzaga University and Washington State University.

Patrick McCurdy is a semiretired physician assistant and Medical Reserve Corps volunteer who estimated he’s given between 300 and 400 doses of the vaccine at various clinics this year.

“Everybody at these vaccination clinics really enjoys it because it’s a small, little part in the big picture of getting past the pandemic,” said McCurdy, who also volunteered during the Hepatitis A vaccine clinics.

Although the logistics of COVID-19 vaccine storage and distribution are more complicated for health district administrators, it’s straightforward for the volunteers on site, McCurdy said. The vulnerable people receiving the doses actually want them, he added, and “you don’t have to convince anybody of its efficacy.”

“All we have to do is get it out, warm it for 10 minutes, and use it,” McCurdy said. “We’re very, very careful not to waste any doses. We want to use every possible dose because it’s so scarce.”

Shelter guests streamed into a small room inside the shelter to receive the vaccine. The process appeared efficient and organized in a way that gave little indication the clinic was set up in just a matter of minutes on Tuesday morning.

Spirits among guests were high.

Brian Washburn felt no ill effects after receiving a dose. He had allergies when he was younger and had to get shots every week.

“I’m used to needles, (but) I don’t like them any better,” Washburn said with a laugh.

Richie Amdal said he wasn’t feeling any immediate effects from the vaccine, but joked that “we won’t know for several months what the reactions are – when you see the horns grow up,” pointing to his forehead.

All kidding aside, Amdal expressed dismay that some are worried about the vaccine’s efficacy.

“What if they felt that way about polio (vaccinations)?” Amdal asked.

The distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine won’t immediately change much about the way shelters operate. Since the start of the pandemic, the health district and shelters have implemented social distancing guidelines and other hygiene protocols that will continue for the foreseeable future.

“We’re looking at it as a pronged approach – this is just one of the tools that providers have – especially because we’re only able to vaccinate a small portion (of the population),” said Kylie Kingsbury, the health district’s homeless outreach coordinator.

On Tuesday, that small portion included Thompson, whose most recent stay at the House of Charity was his second stint in respite care. The amputation was due to frostbite, he said. He’s lived most of his adult life unsheltered, most recently under three wooden pallets covered in a rug downtown.

Most Spokanites likely don’t know Thompson by name, but might recognize him. He used to pull four small trailers behind his wheelchair, often traversing between Mission Park and Coeur d’Alene Park three times a day.

Thompson hasn’t been overly concerned about contracting COVID-19 because he prefers to be by himself, regularly posting up outside in his wheelchair and tuning his radio to the rock’n’roll music of 94.5 FM.

“I sit there and blast my music, and that way I’m alone,” Thompson said.

Obtaining housing is key to Thompson avoiding a fifth surgery and another amputation.

“I can’t get another one because then it’d be up above the knee,” Thompson. “By going to Rose Pointe, I know it won’t happen again.”