A quarter century after its homecoming, a collection of Nez Perce artifacts bears its rightful name

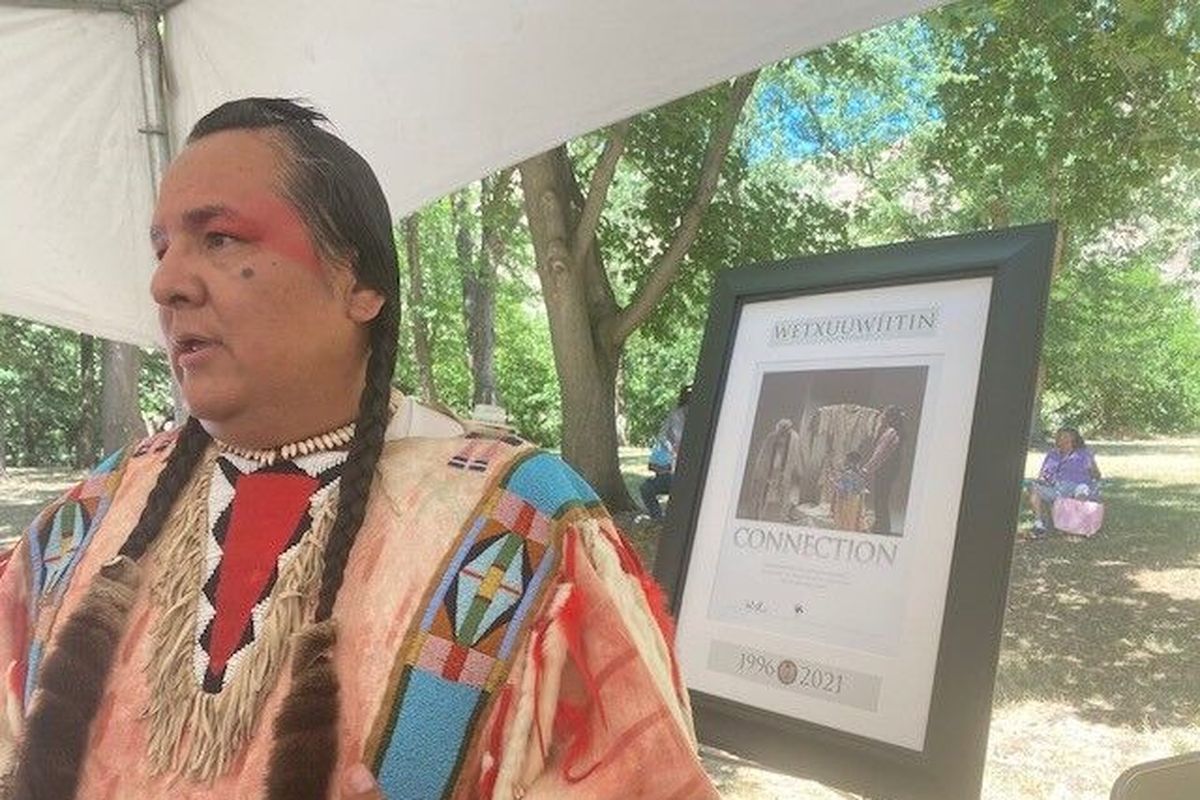

Nakia Williamson speaks about the collection’s significance to the tribe during its renaming celebration at Nez Perce National Historical Park in Spalding, Idaho, on Saturday. The collection of tribal artifacts was returned to the Nez Perce after 185 years away in 1995 and was renamed to reflect its long departure on Saturday. (Riley Haun/For The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

After nearly two centuries, the beadwork embellishing the sleeves and fringes of a woman’s buckskin dress has faded. The cradleboard, which once secured a Nez Perce baby safely to its mother’s back as her horse galloped across a North Idaho prairie, is far too small to hold a modern infant.

The significance of these priceless items to the people whose ancestors created them, though, has never faded. After decades bearing the names of white colonizers who stole them from the Nez Perce Tribe, the collection of horse gear, traditional clothing and everyday tools formerly known as the Spalding-Allen Collection now sits in its rightful place on its homeland and bears its rightful Nez Perce name.

Hundreds of Nez Perce tribal members, leaders, academics and allies gathered at the Nez Perce National Historical Park near Spalding, Idaho, on Saturday to celebrate the collection’s renaming. Its new name, wetxuuwíitin’, means “returned after a period of captivity” in the Nimiipuu language.

Rediscovering lost knowledge

The collection was built starting in the 1840s as Presbyterian missionary Henry Spalding worked to convert the Nez Perce to Christianity. Spalding deemed traditional clothing, regalia and tools incompatible with his goal of assimilating the Indigenous people. He confiscated the items now comprising wetxuuwíitin’ from Nez Perce families throughout his mission work, sending them east to an Ohio sponsor, Dudley Allen, as he went.

In 1976, Bill Holm, a curator at the University of Washington, rediscovered the Nez Perce items in the Ohio History Connection’s basement. Upon hearing of the collection’s existence, the tribe arranged to borrow the artifacts from OHC for display in the Nez Perce Historical Park’s visitor center. Starting in the early 1990s, the tribe sought to permanently reacquire the collection – but the OHC declined to donate the collection, and the Nez Perce paid over $600,000 to repatriate the collection in 1995.

Nakia Williamson, now the tribe’s manager of cultural resources, was a young intern at the Historical Park when wetxuuwíitin’ first came home. Without knowing if the pieces would be here to stay, Williamson and other tribal members set to work documenting every minute detail of each artifact in the hopes of preserving old ways for future generations.

“Names and naming ceremonies are vital to our laws and our culture,” Williamson said at the Saturday renaming celebration. “This is a fulfillment of a promise made 25 years ago. We always knew it deserved a different name, but the battle to acquire what was ours took a lot out of us.”

Accompanied by Nez Perce men performing a traditional song, Williamson led a parade of tribal members on horseback to open the renaming ceremony. The Appaloosa horses and their riders in full regalia circled the park grounds three times, a ritual performed in years past to welcome home fishing expeditions or trade parties.

The traditional costume Williamson wore for the parade reflects the premium placed by the tribe on holding old ways close, he said. His regalia, tanned from hides and intricately beaded by hand ages ago, had been passed down in his family for generations.

Though tribal traditions have always evolved to reflect the resources available to the Nez Perce, Williamson said having access to artifacts from so long ago provides a priceless snapshot of the roots of values held by the tribe today.

Now, future Nez Perce craftspeople will have the chance to see how their ancestors created a celebration dress or an everyday pair of fringed leggings centuries ago by browsing the wetxuuwíitin’ collection.

“No written book taught us how to be,” Williamson said. “Things, like clothing or saddles or cradleboards, passed our values down and reflected our relationship with the land.”

Knowledge for the future

On the outskirts of the circle where tribespeople were gathered listening to elders speak, Trina Webb helped children match the Nimipuu name of each piece of wetxuuwíitin’ to its English counterpart. The bracelet made of tiny ivory shells, for example, is wapk’íilk’il.

“Revitalization is part of the goal here, as always,” Webb, who helps run the tribe’s Nez Perce Language Program, said. “Most young people wouldn’t know the words for these old items in Nimiipuu, so part of renaming the collection is bringing those words back into the forefront.”

The name of the collection also serves to honor a similarly named figure in Nez Perce history. The Lewis and Clark expedition owed its survival in large part to a Nimipuu woman named wetxuuwíis, who had been captured by another tribe and taken far from home in her youth. She returned home with the help of white traders after years in captivity, and reciprocated the kindness they had shown her by persuading her people to assist Lewis and Clark’s party when they arrived sickly and starving in the Nez Perce homeland.

Many in the tribe may not know wetxuuwíis’s story, so the collection bearing her name will help tell it for years to come in addition to preserving Nimipuu culture, Webb said. The name and its history serve as a reminder of the long journey the collection took before it returned home.

“Her story and the story of the collection are a beautiful testament to our strength,” Webb said. “It’s not about who took what or about highlighting the negative, it’s about acknowledging that these things which were never meant to return have come home now. It’s about continuing to grow what we lost.”

Gia Paul, a Nez Perce artist, felt the reverberations of ancient traditions when the horses on parade strode proudly by. Her work focuses on clothing that mirrors old tribal methods and motifs while using modern techniques, and the dress she displayed at the renaming celebration was commissioned by the event’s planning committee to honor the collection and its new name.

Paul pored over notes left by Henry Spalding to create a garment that would reflect the value and significance of the dresses and other clothing in the collection. Spalding’s notes indicated that each handworked Nimipuu dress would have cost three horses in trade – an exorbitant price considering the high value placed on horses by the tribe. Paul’s design depicts three horses loping across the skirt’s hem.

“It’s the highest honor to be part of bringing the collection home and being here for its naming,” Paul said. “The history is undeniable and it serves to remind the world and all of us that we’re still here and still standing.”

Paul’s two children played nearby, both wearing buckskin garments appliqued with horse motifs. To Paul, being present for wetxuuwíitin’’s renaming shows the importance of continuing to invest in Nimiipuu culture and involving young members of the tribe.

“The collection’s return proves there is a direct link between us, our past and our future,” Paul said. “It shows how the past can still be a central part of our present world.”