We the People: Flag Day is this week, and what you know about Betsy Ross is probably not right

Each week, The Spokesman-Review is examining one question from the exam taken by immigrants trying to become United States citizens.

Today’s question: Why does the flag have 13 stripes?

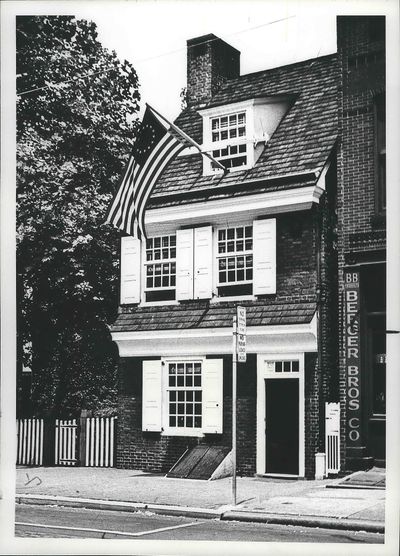

Many remember learning the story of Betsy Ross and the original American flag at some point in their life. Images show Ross, a seamstress from Philadelphia, sewing the original red, white and blue stars and stripes on a flag in her lap.

In this first flag, the 13 red and white stripes and the 13 stars represented the original North American colonies. The flag we know today still has 13 red-and-white stripes to represent the colonies and 50 white stars on a blue square to represent the current number of states.

But the story of the original flag and Ross’s involvement is a bit more complicated than what many might remember learning in grade school.

Marla Miller, director of the public history program at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, decided to study Ross’s life after researching women in the clothing trade and realizing how misunderstood many women were during the 18th and 19th centuries. She then wrote “Betsy Ross and the Making of America,” and found how important Ross’ legacy is to understanding the founding of the country.

Ross’ story has been shared for generations, but it’s often misremembered, Miller said.

Ross never claimed to make the first flag, Miller said, citing affidavits from her family. In Ross’s version of the story, she instead bragged about meeting George Washington and making a small edit to the design of the flag.

The flag design given to Ross originally had a six-point star, but Ross took a piece of fabric and with one cut created a five-point star instead.

The decision to change the type of star is often seen as design-based, but Miller said it was all about meeting production needs. Ross knew the country would need a lot of these flags, and fast, Miller said. Making a five-point star was much easier than a six-point star.

In images of her sewing the flag, Ross is always shown in domestic settings, Miller said, often by a window with children around her.

“It’s very much sentimentalized,” Miller said.

In reality, the flags were likely way too large to be held in one person’s lap, Miller said. They were probably made in trade shops by multiple people.

Ross was more than a domestic seamstress; she was actually a successful tradeswoman and businesswoman.

Ross began working in the upholstery trade as a teenager and she didn’t retire until she was in her 70s.

Much of her later career was spent making flags for various government agencies. There’s ample evidence she went on to become a government contractor, Miller said.

Ross then trained her daughter and founded a multigenerational business.

“I think of her as a resilient and skilled artisan,” Miller said.

The story many know of Ross – a woman playing a large part in the revolution by sewing the first flag – actually served a larger purpose, Miller said.

Ross’s role in the revolution didn’t really come to light until after the Civil War, as the country was heading into its centennial and looking to celebrate those who founded it. During the Women’s Suffrage Movement, when many weren’t yet on board, Ross’s story became an example of how essential women were to the founding of the country, Miller said.