After 20 heat-related deaths, some say Spokane region needs better planning for future heat waves

With temperatures well over 100 degrees on June 29, 2021, Spokane firefighter Sean Condon, left and Lt. Gabe Mills, assigned to the Alternative Response Unit of of Station 1, check on the welfare of a man in Mission Park in Spokane. (Colin Mulvany/The Spokesman-Review)

As summer heat began to blanket Spokane, it was more than meals that city of Spokane Meals on Wheels volunteers were delivering to clients.

The nonprofit worked to deliver fans to people who did not have air conditioning and needed fans to stay cool, starting in May.

They didn’t realize how crucial those fans would be come June.

Meals on Wheels Spokane serves about 500 clients who live in the city, and as of last week, volunteers have delivered 260 fans so far this year.

Despite the fan distribution and concerted efforts to keep vulnerable seniors safe, some of the nonprofit’s clients died from the heat when temperatures reached record highs.

“It was so devastating; we did lose clients to the heat wave that were found by welfare checks or went to the hospital,” said Sarah Hall, development director of Meals on Wheels Spokane. “Some had A/C and some didn’t, and it seems like there’s no telling exactly what happened.”

All of the clients served by Meals on Wheels in Spokane are considered homebound, meaning seeking refuge in a cooling center was not an option unless they could find a ride.

Climate scientists and public health experts say that heat-related deaths are preventable, yet 20 people died in Spokane County from causes believed to be related to the heat wave, along with more than 90 people statewide.

After the unprecedented heat wave hit the Pacific Northwest a few weeks ago, some leaders believe they did the best they could to protect and prepare residents in Spokane County, while others say there’s a lot more work to do and are asking two big questions: Why wasn’t the community prepared? And what needs to be done to prepare for next time?

What the health district did

In the past 30 years, heat has killed more people nationally on average than tornadoes, floods or hurricanes, according to the National Weather Service, yet preparedness plans in Spokane County hardly account for this.

Spokane County’s severe weather hazard plans cover tornadoes to volcanoes, but there is no plan for a heat wave.

The Spokane Regional Health District’s emergency response plan lists extreme heat as a hazard, but there are no plans in place to address heat, including completed local studies about who is most vulnerable.

When the National Weather Service forecast the record heat wave, the Spokane Regional Health District began to prepare. Thanks to the pandemic, it didn’t have to pull together the incident command team because they’d already been meeting for a year and a half.

While the health district views itself as a key player in the response to a heat wave, it is not necessarily the designated leader in the county’s response, said spokesperson Kelli Hawkins.

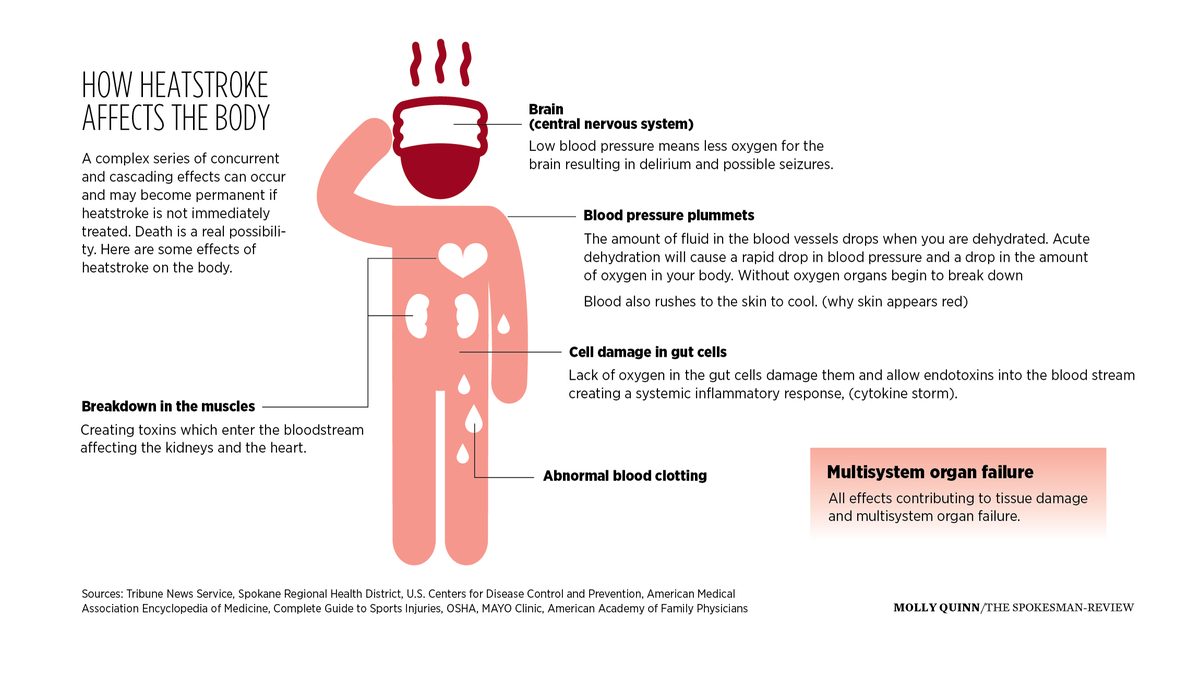

A large part of the public health response to the heat wave was ensuring that the information disseminated to partners and the media was accurate and comprehensive, so people knew what symptoms to look for and where to go to stay cool.

The health officer also has the ability to declare a public health emergency, but Turner said the threshold for such a declaration is usually when the district has exceeded its resources and capacity to respond to the situation.

“I don’t know that we felt that need (during the heat wave) because we did everything we as public health could as an agency to communicate to reach out to those marginalized communities,” said Tiffany Turner, the district’s preparedness response manager .

The health district sent out a news release ahead of the heat wave on June 25 outlining the symptoms of heat stroke and exhaustion as well as a list of cooling centers in Spokane and Spokane Valley. There were also district teams on the ground during the heat wave disseminating information and water to those who needed it.

Hawkins and district leaders reached out to partners, including the city of Spokane and Avista, with whom they shared a list of people and facilities with health needs that are dependent on electricity, in order to ensure group homes and adult family homes retained power or got it back quickly.

“(The heat wave) was something our county has never experienced to this extent before so maybe it is something we need to look at from a community response,” Turner said. “How do we go about that next time?”

Turner said the health district will likely update its hazard planning around extreme heat following this year’s heat wave, and she said planning ahead for the next one is a part of that reflection.

“Now we’ve been through it and now we know we need to have a more robust response or preparation for that, because it may happen this season, next season or in 20 years,” she said.

What the city did

Spokane Mayor Nadine Woodward has vigorously defended the city’s rapidly conceived response to the heat wave but also pledged to improve in future weather emergencies.

The city opened the Looff Carrousel in Riverfront Park as a cooling center, with two nearby buildings serving as a backup. It then added hours at Spokane Public Library branches to offer neighborhood-based cool spaces.

Altogether, the maximum capacity was about 1,000 people, according to city officials.

The Looff Carousel was used by 731 people over the heat wave, with no more than 33 people inside at any one time.

The city’s communication efforts to alert people about warming centers included an online newsletter, traditional media outlets, social media, and even paper flyers distributed by outreach teams working with the homeless population, said city spokesman Brian Coddington.

There is no book or plan in City Hall that specifically calls for the Looff Carousel and library branches to be used as cooling centers. The system was erected on the spot as the heat approached, based in part on the city’s experience providing emergency shelter during last summer’s wildfires.

She criticized the Spokane City Council’s emergency ordinance, adopted last week, that lowered the temperature threshold to open cooling centers. The new law also demands the administration devise a comprehensive sheltering plan for weather emergencies. It could quadruple the number of times the city has to open cooling centers in a given year, Coddington said.

Rather than have the City Council dictate the parameters for emergency shelter, Woodward said she wants to bring together providers such as Volunteers of America and Catholic Charities to gather input on future plans.

Woodward said city residents also have to ask “what are we doing as a community to look after each other?”

Spokane City Council President Breean Beggs drafted the amendments to an existing law that requires the city to provide shelter during extreme heat, smoke and cold. In part, this ordinance was a reaction to the city’s initial plan, which offered just 30 spots at the Looff Carrousel.

“In the past we could get by without a plan and now with this summer we’ve learned we can’t if we want to prevent deaths and ER visits and all the expenses of that,” Beggs said.

The ordinance requires the city to publish a plan for emergency warming, cooling and safe air centers by Sept. 30 each year.

The City Council expanded the ordinance to include not just people experiencing homelessness but also those who are vulnerable in heat waves. There is no data readily available that shows how many households in the city or county are without air conditioning.

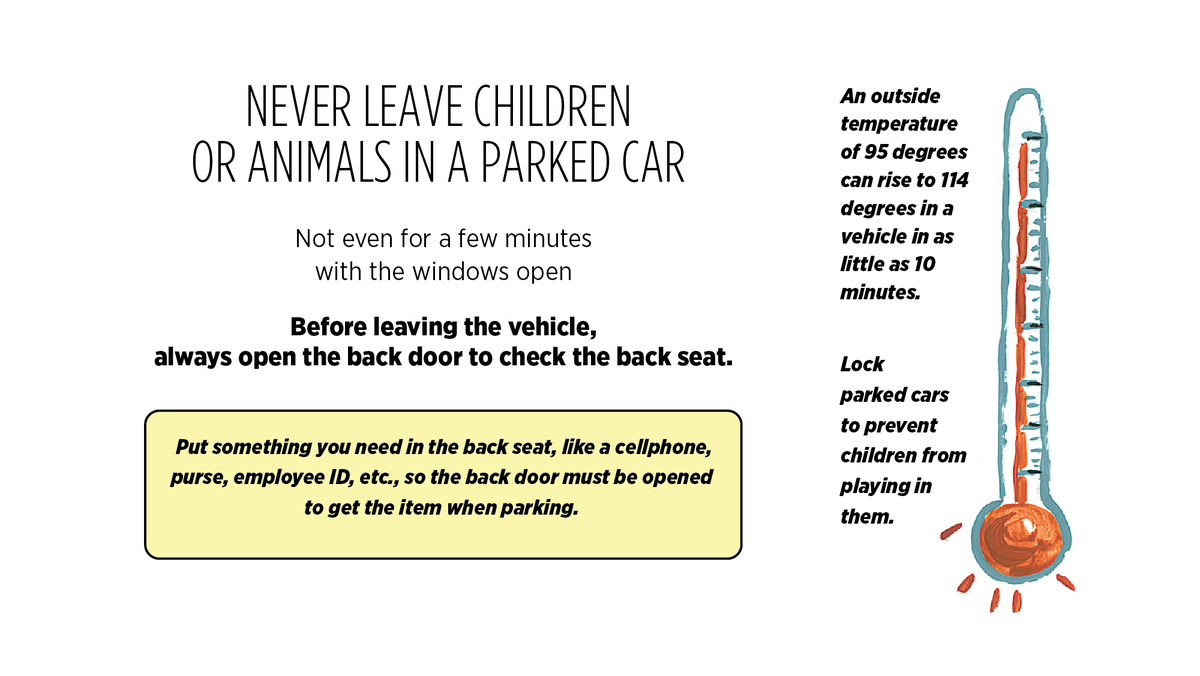

Of the 20 people who died during the heat wave, the majority of them were at home without air conditioning, according to the medical examiner. Just one of that group was a person without housing.

Beggs hopes the updated weather shelter ordinance will provide a direction for the city to plan for in the coming months.

The ordinance sets thresholds at which the city is required to open cooling centers, including both maximum daytime temperatures over 95 degrees for several days in a row as well as night time temperatures that do not get below 70.

Climate and health researchers pinpoint rising nighttime temperatures as an increasingly relevant problem as global warming progresses.

Dr. Ashley Ward, at the Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions at Duke University, has studied climate change, heat and its impact on public health in the Carolinas. She said warming nighttime temperatures, around 75 or higher, paired with daytime highs of 95 or hotter is when people start to get sick.

“When overnight temperatures don’t drop below a certain temperature or degree the body doesn’t have time to recover,” Ward said.

Temperature thresholds could vary for individuals as well as for regions. Older people or those with underlying health conditions, including pregnancy, might be a higher risk for heat-related stroke or illness.

Regardless, “health impacts are happening long before warnings are issued,” Ward said.

Transportation gaps

Before the heat wave, several agencies, including the health district and cities, released the locations and hours of cooling centers in Spokane and Spokane Valley. There were no transportation options listed at the time, however.

Many of the community’s most vulnerable residents would need that transportation to get to a cooling center.

“If we offered them a cooling center, it would fall on deaf ears because almost all of them don’t drive,” said Hall, with Meals on Wheels. “Some of them don’t have families or support systems or they wouldn’t call an Uber.”

With no emergency plan to lean on, some of the services offered in Spokane were hastily assembled as the heat wave approached – or was already in full force.

A four-day partnership between Avista and the Spokane Transit Authority offered free door-to-door van rides to anyone in the region who needed transportation to a cooling center.

The idea came about as Avista implemented rolling blackouts in Spokane in the face of surging demand and searing temperatures. Latisha Hill, Avista’s vice president of community and economic vitality, reached out to her friend Lisa Gardner, the Spokane City Council’s director of communications, to ask how Avista could help.

“I was explaining to her that we really need to figure out how we’re getting people to these cooling centers,” Gardner said.

Avista then offered funding to STA, which hatched a plan.

Brandon Rapez-Betty, STA’s director of communications and community engagement, recalled STA’s program to provide free rides on paratransit vans to vaccination clinics. Using the same model for rides to cooling centers seemed like a no-brainer.

The service was put into action in less than a day.

The STA announced the service along with a phone number for anyone – not just those within areas affected by blackouts – to call for a free trip to a cooling center.

Word spread quickly.

“It was our best performing social media post we’ve ever had,” Rapez-Betty said.

But that didn’t translate into ridership. There were fewer than 10 rides in the four-day period they were available.

The low ridership might reflect the need for a shared, well-understood regional plan in heat emergencies that people understand and know before the high temperatures hit.

“Going forward, there needs to be a plan of action,” Gardner said.

Rapez-Betty said STA already is conceiving a long-term, standard response plan when certain heat thresholds are met.

What constitutes an emergency

During an extreme weather event like a tornado, tsunami or flash flood, the National Weather Service sends out text message alerts to those in the affected regions.

These alerts are not generated at the local level, however, and only certain weather events can trigger such a text alert.

A heat wave is not on the list. This meant that despite the extreme heat dome in the forecast and potential for heat-related illness and death, the local National Weather Service office could not send out emergency text alerts to cellphones .

“We don’t have control at the local level; it’s automated at the national level,” Andy Brown, warning coordination meteorologist at the weather service in Spokane, said.

That meant Brown and his team relied on local partners to disseminate information, take their extreme heat warnings seriously and possibly disseminate their own emergency alerts.

State and county authorities could have sent out alerts about the danger of the heat wave, but none did.

“We knew well in advance that this was coming, so there was no need to do an alert per se, because there was no time sensitivity to it,” said Chandra Fox, deputy director of Spokane County Emergency Management. “Alerts have to do with imminent threat and time sensitivity.”

Emergency alerts are a part of heat action plans that other cities, such as Chicago, have adopted in response to heat waves.

Ward said research shows that early warning systems do work, especially when regions have established plans for how to disseminate information.

What needs to be done

In order to prevent deaths and adequately prepare communities for heat waves, officials must know who’s the most vulnerable in the community. Ward gives the example of a rural mountain town in North Carolina that has an ice storm plan to support its most vulnerable residents when the power goes out.

The volunteer fire department keeps a list of those who are elderly and live alone and makes it a priority to check in with them to ensure they do not freeze to death.

Plans need to be specific to the hazard they are addressing, Ward said.

“Different groups of people are vulnerable to different hazards in different ways,” she said.

During the heat wave, the Spokane Valley Fire Department reached out to the Greater Spokane County Meals on Wheels list to check on vulnerable seniors during the weekend when volunteers weren’t delivering meals.

“We gave them a list of our top-priority people that we’re concerned about already, and they helped us do another check in the heat wave,” said Janet Dixon, director of development at Greater Spokane County Meals on Wheels.

Dixon is aware that they aren’t reaching everyone, however, leaving gaps in who got checked.

“What if you haven’t signed up for Meals on Wheels?” she said. “We have a lot of people who are resistant to sign up, and they think they aren’t in a dire enough situation.”

Heat and drought are harder disasters to prepare the public for because nothing visibly changes outside. Whether emergency alerts would prompt action is questionable.

“A significant piece of this is that personal responsibility and personal choice: that is an issue we struggle with continually because people have the option to ignore the information and they have the option to not take protective steps to help themselves,” said Fox, with Spokane County emergency department.

During the extreme heat, Fox and other public officials urged the public to check on their neighbors and those who live alone or without air conditioning.

Ward said that while urging people to check on their neighbors sounds good, it’s more effective to engage with organizations like Meals on Wheels, which already work with vulnerable or at-risk individuals.

“I think what’s effective is leveraging the networks that already exist in communities to help not only develop a proper response but to develop proper messaging,” Ward said.

Dixon, with Greater Spokane County Meals on Wheels, is unsure that all residents would look for cooling centers even if transportation is available to them. Understanding how to communicate the dangers of heat is a part of what planning should involve.

Ward warned that planning should not be completed by officials isolated from the people most affected by the problem.

What comes next

City law requires that Spokane offers shelter and protection to vulnerable people during heat waves, which is a part of why the city responded with cooling shelter plans.

The state Department of Health, which took the lead on the statewide heat response, emphasized that emergency response starts locally. The state still is working to ensure cooling centers are open and people can find them.

“We have recently added cooling centers to the Washington Tracking Network to make that information more accessible, and people can call 211, the statewide resource for local essential services, to find cooling centers and other help in their area,” said Lauren Jenks, assistant secretary of health.

During emergency events, counties can ask the state for help if they need more support, including water and air conditioners.

Very few counties asked for state support during the heat wave, according to the Washington State Military Emergency Management Division, however – despite the more than 90 deaths reported statewide.

Spokane County Commissioner Mary Kuney has asked for a briefing on the county’s response to the heat wave. The county funds the local emergency department as well as the health district.

Kuney said the response should include not just local government but community organizations and members too.

“Partly, I think it’s going to be how do we inform citizens to know who they call to say they need help?” Kuney said. “If they’re homebound, providing STA bus rides doesn’t help if they can’t get out of their environment.”

In hindsight, Beggs wishes the city had erred on the side of too much preparedness.

“I am hoping by the time we get to 2022 it will be very different,” he said.

Temperatures still are lingering in the mid-90s in the Inland Northwest. Climate change will exacerbate events like this year’s heat dome, making them more frequent and more intense, experts say.

Even if heat waves like the one seen this year don’t roll through in the coming years, global warming will continue to raise baseline temperatures year over year.

“Hopefully this is a lesson learned that is not a lesson forgotten,” said Dr. Bob Lutz, Spokane County’s former health officer who now works for the Department of Health. “We need to be proactive and we need to say we cannot allow this to happen again.”