Death of a fly-fishing hero: John Maclean writes the history behind ‘A River Runs Through It’

”After you have finished your true stories sometime, why don’t you make up a story and the people to go with it? Only then will you understand what happened and why. It is those we live with and love and should know who elude us.” – “A River Runs Through It and Other Stories,” by Norman Maclean

BILLINGS – Almost salmon-like in its brawny proportions, the 7- to 8-pound rainbow trout John Maclean reeled in while fishing the Blackfoot River left him awestruck.

“I’d never seen a Blackfoot rainbow that big before, never,” he wrote of the catch-and-release experience for a magazine article.

The story was read by an editor for HarperCollins Publishers who contacted Maclean and asked if he would consider expanding the article into a book about his well-known family and its ties to Montana.

“The book just grew from no initial plan to what it eventually became,” the 78-year-old author said in a recent telephone interview. “I call it a chronicle.”

New book

Recently released, “Home Waters, A Chronicle of Family and a River” delves into the background of what is the most famous Montana fishing story written – “A River Runs Through It and Other Stories,” published in 1976. Written by Maclean’s father, University of Chicago English professor Norman Maclean, “A River Runs Through It” has attained cult status.

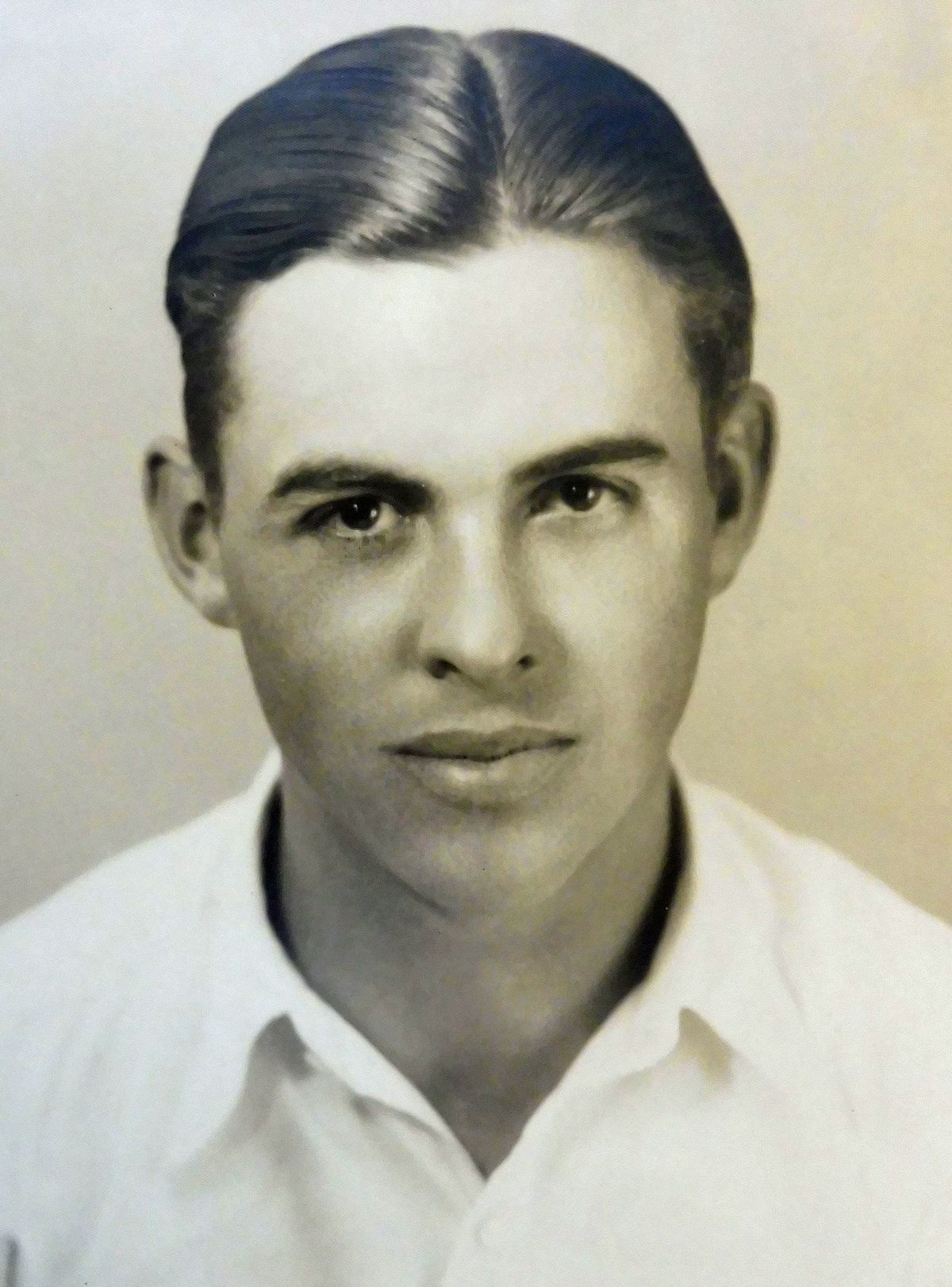

The 1992 movie of the book, directed by Robert Redford and starring Brad Pitt, popularized fly fishing and Montana to a degree unimaginable, driving hordes of neophytes into fly shops and onto streams across the country. Thanks to the book and movie, Pitt’s character – based on Norman’s brother Paul Maclean – has become mythological in his fly-fishing abilities, as well as shrouded in mystery for his unsolved murder. Paul was killed in 1938 at age 32 while working as a University of Chicago publicity writer. Norman fictionalized his brother’s death in “A River Runs Through It.”

Paul

Given this history, it’s no wonder John was initially hesitant to wade into his family’s history to write a book. His father had wanted to name him Paul, and “A River Runs Through It” is filled with Norman’s sorrow over his inability to save his troubled brother.

“I don’t want to knock the guy, but it was kind of a meaningless death,” John said. “I mean, my dad spent his life trying to make something bigger out of it, even if it was only a gambling conspiracy. Anything to elevate it from Paul stumbling around drunk and getting beaten to death. Which is I think what it was.”

In “Home Waters,” John based his recounting of Paul’s death on police records and conversations with his mother and father.

“I think that account in ‘Home Waters,’ nobody is going to get beyond that one,” he said. “One reason I made it so specific and kind of rough is that I don’t like what’s been done … all the falsity about it.

“A certain romanticizing of it in a ‘River Runs Through It,’ I can live with that. But the cult kind of stuff and silliness, and the ‘I’m the one who killed Paul,’ or it was all a great conspiracy by some gambling syndicate, or he was a private investigator for the university and uncovered too much because he was this great investigator and so they caught him and killed him. Crapola.

“The facts, once you know them, tell the story, and you don’t need a lot of gloss.”

Norman

The depth of Norman’s sadness over his brother’s death is further revealed in John’s book where he quotes from a letter his father wrote to Nick Lyons. Lyons had written a favorable 1976 review of “A River Runs Through It” for Fly Fisherman magazine.

“I should like to think that the story, A River Runs Through It, is somewhere near as good as you say it is, not so much for my sake as for the memory of my brother whom I loved and still do not understand, and could not help,” Norman wrote.

“After my father’s death, there was no one – not even my wife – I could talk to about my brother and his death. After my retirement from teaching, I felt that it was imperative I come to some kind of terms with his death as part of trying to do the same with my own. This was the major impulse that started me to write stories at 70, and the first one naturally that I wrote was about him. It was both a moral and artistic failure. It was really not about my brother – it was only about how I and my father and our duck dogs felt about his death. So I put it aside. I wrote the other stories to get more confidence in myself as a story-teller and to talk out loud to myself about him. The story, which now stands as the first one in the book, is actually the last one I wrote. I hope it will be the best one (although not the last one) I ever write, and I thank you again for writing beautifully about it.”

Footsteps

Although Paul has gained literary fame, in real life he was persistently following in his older brother Norman’s footsteps. Like his brother, Paul attended college at Dartmouth. He later landed a job through Norman at The University of Chicago, after being fired from his statehouse political reporter job at the Helena Independent Record.

John attributes his own journalism career at the Chicago Tribune, which began at age 21, in part to Paul. But he winces at his uncle’s elevation to “the god of fishing” in many readers’ or movie-watchers’ minds.

“He’s not here, and he doesn’t have to prove it, so he’s got eternal life,” John said.

In death as in life, Paul managed to cast a long literary shadow across the Maclean family.

“ ‘A River Runs Through It’ would never have been written if Paul hadn’t come to a bad end,” John said. “ ‘Home Waters’ never would have been written if Paul hadn’t come to a bad end. So he has had an afterlife, and I think a positive one.”

His father’s story about Paul resulted in numerous readers reaching out to Norman and recounting their own dealings with troubled siblings they had tried, unsuccessfully, to help.

“I read your book and felt that you understood me,” John said they would write. “Now that’s a pretty good legacy.”

Norman died in 1990. His second book, “Young Men and Fire” – about the deadly 1949 Mann Gulch fire north of Helena – went to press in 1992. John and his sister, Jean Maclean Snyder, completed their father’s book posthumously.

Legacy

Resurrecting his family’s history in “Home Waters,” despite the success of his own five books on wildland firefighting and a 30-year journalism career, was “scary as hell,” John said.

“How would you like to write books that are compared to ‘Young Men and Fire’ and ‘A River Runs Through It?’ ” he asked.

In John’s first book – “Fire on the Mountain: The True Story of the South Canyon Fire” – published in 1999, he decided to actively avoid any comparison to his father’s poetic prose.

“So I wound up, actually, simplifying my writing style a bit, just to keep it away from any kind of an imitation of my dad, and being almost deliberately journalistic about it,” he said. “If I were to do it today, I wouldn’t do it that way. But it was appropriate at the time for me to do it that way because I was trying to establish an independent identity, realizing that I was moving along in my father’s wake.”

As a result of his book’s success, John said he became “the court of last resort” in the wildland firefighting community for writing about and publicizing fatal forest fires. When reports were finalized and family or those involved disagreed, they contacted him in hopes John would investigate and provide greater clarity.

The success of his books has established John’s fame, separate from his father’s. “Fire on the Mountain,” he proudly noted, will be around long after he’s gone.

Unlike his first firefighting book, however, in “Home Waters” John chose to embrace more poetic prose, a less journalistic style and even dip into the realm of holy waters. From the perspective of his age, and with time for reflection, he communicates the enormity of relationships in the context of what is often referred to as a sport, activity or pastime – fishing. He concludes his family chronicle by returning to where the story started – maybe where it has always drifted – by talking about fishing, catching fish and catching big fish.

“Size counts, but in my family, fishing means more than catching fish that can be measured in inches and pounds,” he wrote. “There has to somehow be a link to the past, a present moment of consequence, and God knows what all else to make it complete. We fish as a way to communicate with each other, living and dead. We fish to keep a present hold on Montana and to recall the frontier Eden it once was. We fish to compete against each other – living and dead. We fish because it’s the family legacy, a demanding craft handed down from one generation to the next.”

Now, even when John fishes alone on the Blackfoot River, he is not by himself.

The “presence of the generations of his family” accompanies him. He has become “a thread in a broad fabric long in the making.”

Ghosts haunt the waters, and big fish rise in his memory.