Getting There: Preservationists seek to protect the South Hill ‘s architectural legacy, celebrate its streetcar connection

An STA bus heads west on 14th Avenue past old streetcar rails on Madison Street in Spokane. (DAN PELLE/THE SPOKESMAN-REVIEW)Buy a print of this photo

Before the streetcar, there wasn’t much to Spokane’s South Hill.

While Browne’s Addition boomed, the steep incline of what was called Cannon Hill kept it largely unpopulated. It was just too precipitous for most commuters, especially considering the mode choices of horse and foot. Instead, Seventh Avenue was the tony edge of town, reserved for the city’s elite of bankers, senators, businessmen, doctors and lawyers.

But when the streetcar came, so did the South Hill – as a neighborhood, anyway.

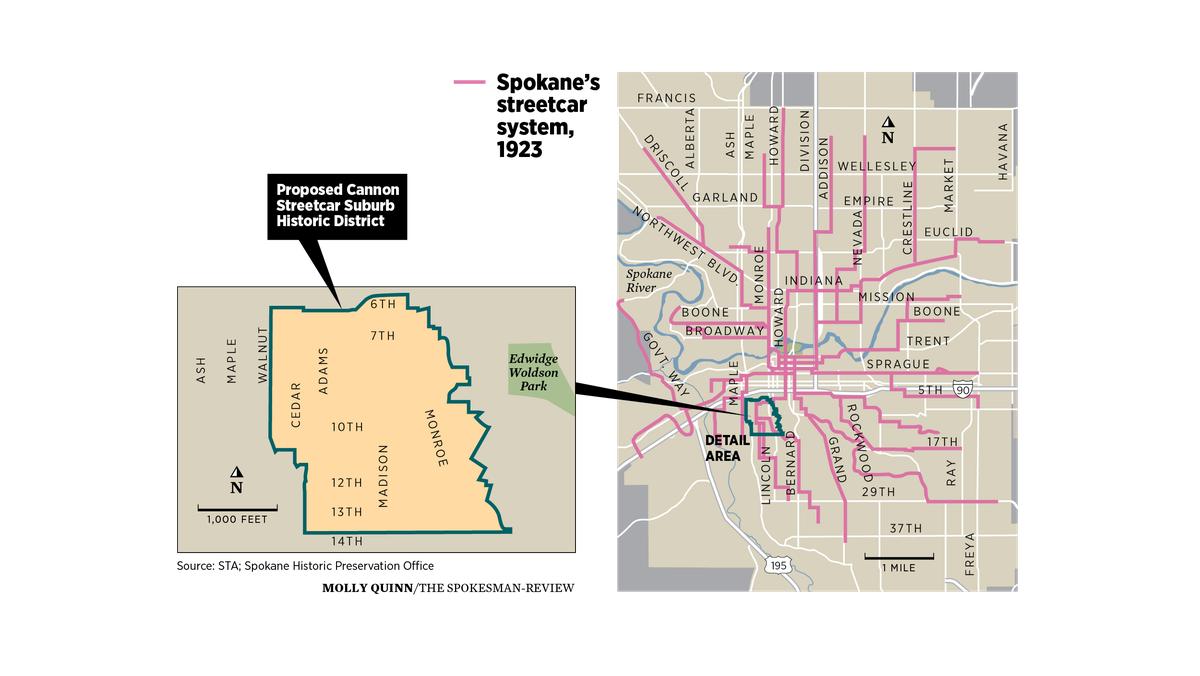

If Spokane is a town built by the electric streetcar – and it is – then the lower South Hill is the prime example of how that particular type of transportation shaped, and continues to shape, our community.

When you drive up the steep face of the Monroe Street hill, thank the short-lived Spokane Cable Railway, which began running the same year Idaho was admitted to the union. When you commute on Maple or Madison or Jefferson or Adams or Ninth or Fifth, keep in mind those roads were originally built for the Spokane Street Railway Company’s Cannon Hill streetcar line. And if you happen to live on the lower South Hill’s 146 acres, chances are you live in a house built by someone who took the streetcar to work, school, shopping or for any other errand of the day. In other words, thank public transportation for the existence of one of Spokane’s defining neighborhoods.

Beginning this month, Spokane’s Historic Preservation Office is holding a series of virtual workshops to discuss a project to protect the architectural history of the neighborhood and celebrate its specific connection to streetcars.

Logan Camporeale, a historian with the preservation office, said before the introduction of electric streetcars, there was no real feasible way up the hill.

“It was a topographical challenge,” he said.

Unlike the Browne’s Addition neighborhood, which had about 90 homes built before 1899, only 22 were constructed on the lower South Hill before 1899. The neighborhood was “sprinkled with houses. Very lightly sprinkled,” Camporeale said.

The short-lived and financially doomed cable car, which ran from 1890 to 1894, was replaced by the electric Cannon Hill line, reflecting how Spokanites referred to the South Hill at the turn of the century.

“Then it goes really ballistic after that. From 1900 to 1910 , the first 10 years that there’s reliable streetcars, there are 264 homes built that still exist,” Camporeale said. “It goes to show that if you build reliable public transportation, it will lead to a housing boom, at least in this time.”

Any stroll on the lower South Hill gives evidence to what Camporeale and the historic office already have quantified: nearly two-thirds of existing homes were built during the age of the streetcar.

Those homes run the gamut. Mansions sit next to duplexes that abut apartments that are neighbors to bungalows. The proximity to downtown Spokane and the frequency of streetcars made the neighborhood appealing to everyone.

Even wealthy people were excited to live near the line, an idea that might surprise modern commuters. When the Cannon Hill line was finished, an article in the Spokane Chronicle was headlined, “Lawyers Will Stop Walking: The New Cannon Hill Line is Nearly Ready for Use.”

The lots closest to the streetcar line were sold first, and the homes were built to face the streetcar, a sign that the vehicle was embraced, not shunned.

“They were proud of it and excited about it,” Camporeale said.

But it wasn’t just the One Percent. The first duplex in the proposed historic district was built in 1906, and the first apartment complex in 1908. In this time, African American and Jewish Spokanites were among those who made this neighborhood their home.

More than 120 years after the streetcar line began operating, public transportation continues to run similar routes as the streetcar did, something not lost on the neighborhood’s residents.

“People have asked me, ‘Why is the bus going through the neighborhood?’ ” Camporeale said. “Because literally, it always has.”

Of course, the world has experienced a lot of change thanks to the automobile. The advent of the internal combustion engine, not to mention the financial incentives the government supplied for the new form of transportation, led to the streetcar’s demise. Farther- flung homes and highway commuting became commonplace. Tailpipe emissions became the No. 1 culprit for climate change in Washington.

But according to Camporeale, the lower South Hill is the same as it ever was, or at least close. The diverse mix of housing and income levels remain in the neighborhood, as they have since the day of the streetcar.

“When people say this (historic preservation proposal) is anti-development, I disagree,” he said. “There are a lot of apartments. A lot of small bungalows. Yeah, there are some mansions mixed in, but in my mind this is a lot different than trying to preserve homes around a golf course.”

In other words, if the point is to preserve the historic character of the neighborhood, that means preserving the myriad apartments, single-family homes and, yes, mansions.

“A lot of what we’re advocating to protect is multifamily that’s still in use today,” Camporeale said. “This wouldn’t prevent new apartments from being built. Are there places in the neighborhood where a new apartment makes sense? Absolutely there are.”

A simple majority of the neighborhood’s property owners have to approve of the Cannon Streetcar Suburb Historic District. If they do, the preservation office would help guide property owners in keeping historic buildings in use and intact, provide financial incentives to rehabilitate old buildings and review permits for demolition and new construction.

If the South Hill district is approved, it will join the existing Booge’s Addition, Shadle-Comstock and Ninth Avenue historic districts.

A similar historic district was approved by property owners in Spokane’s Browne’s Addition in 2019.

If all this sounds familiar, the preservation office was working on the district early in 2020, but had to set it aside due to the pandemic.

For more information, visit HistoricSpokane.org/Cannon.

Road work

First Avenue, between Howard and Bernard streets, and Washington Street, between Pacific and Sprague avenues, will have lane restrictions on Wednesday.

The northbound curb lane of Wall Street between Country Homes Boulevard and Holland Avenue will reopen this week after a month of closure related to telecommunications work.

Wall Street between Third and Second avenues will be closed on Thursday for Avista work.

Spokane Falls Boulevard will be reduced to one lane between Browne and Bernard Street today through Friday for telecommunications work.

The northbound lane of Bernard Street between 19th and 17th avenues will be closed, with flaggers, in both directions until Jan. 29 for telecommunications work.

Geiger Boulevard has lane restrictions between Soda Road and Spokane city limits as crews work to remove the existing roadway. Motorists should use an alternate route, such as Electric Avenue or Thomas Mallon Road.

The work will be complete this summer.

Editor’s note: This story was corrected on Jan. 11, 2021 to correct a quote that was inaccurately typed into the story. The correct version is: “Then it goes really ballistic after that. From 1900 to 1910, the first 10 years that there’s reliable streetcars, there are 264 homes built that still exist,” said Logan Camporeale, a historian with the Spokane Historic Preservation Office. “It goes to show that if you build reliable public transportation, it will lead to a housing boom, at least in this time.”