Bill Watterson, other artists reflect on 1995, the year that comics changed forever

Bill Watterson reflects today and marvels at the perch syndicated strips once held, back when the comics page was part of the nation’s daily cultural conversation. “The reach and impact of newspaper comic strips,” Watterson says by email, “is almost impossible to fathom now.”

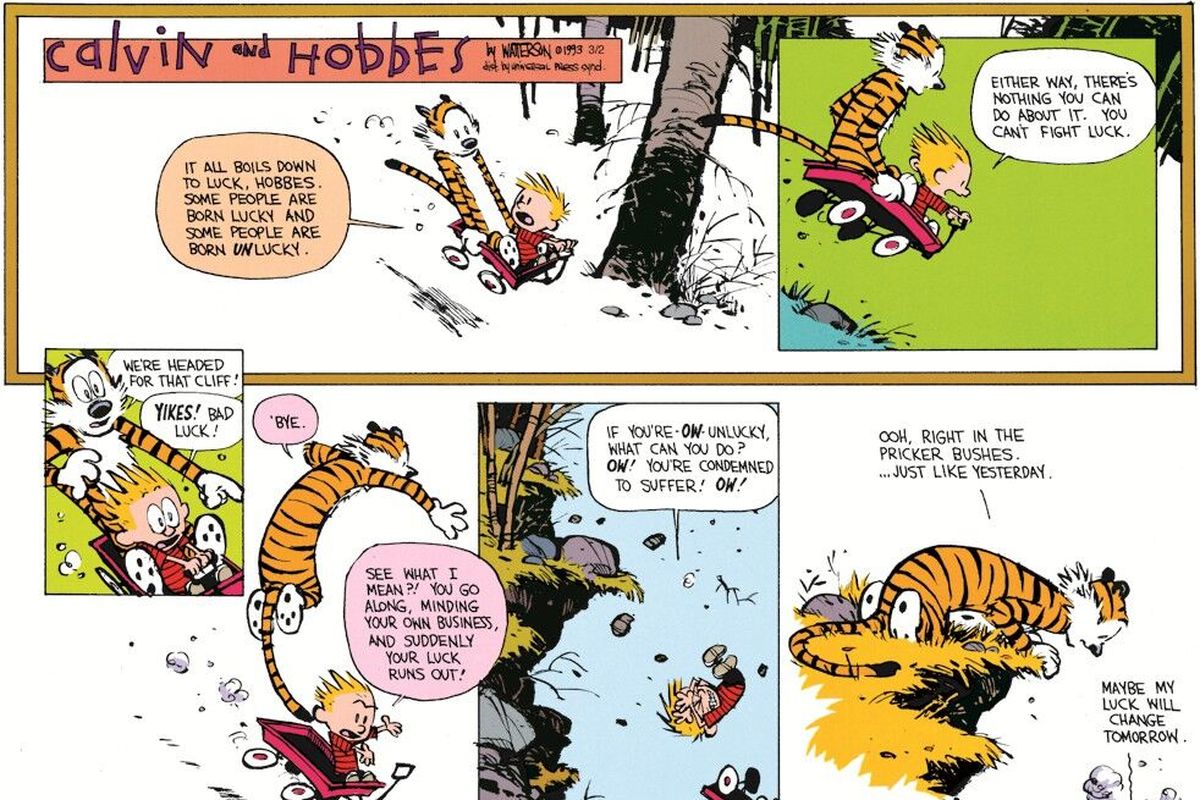

Watterson created “Calvin and Hobbes” for a decade, when the strip was syndicated to 2,000-plus newspapers. When his comic ended its run a quarter-century ago this week – on Dec. 31, 1995 – the departure capped a seismic year of farewells by superstar strips: Gary Larson had retired “The Far Side” that January, and Berkeley Breathed had ended his Sunday-only “Bloom County” spinoff, “Outland,” that March.

“This was three Hall of Famers walking away in their prime,” says Andrew Farago, curator of the Cartoon Art Museum in San Francisco. “I don’t think anything like that had happened before, or has happened since, in comics.”

All three features had been a daily morning must-read for multitudes – exactly a century after Richard Outcault’s “Hogan’s Alley,” featuring the Yellow Kid, first helped spur the rise of Sunday color comics as big audience draws.

“A cartoonist could talk to tens of millions of people, from all walks of life, every single day, year after year,” Watterson says. “Newspaper comics were about as democratic an art as you can get. The mass media had its faults, but I do miss the way it created a shared cultural experience.”

Other stellar strips continued to attract many readers after 1995, and Watterson notes that in the early 2000s, Richard Thompson’s “Cul de Sac” proved that the launch of great new comics was still possible. But that, he says, was during the era when “the internet came and blew apart the newspaper ecosystem.”

“A lot of the technological change has been exciting, but it’s really changed how creative works are valued,” says Watterson, noting that if cartoon art can be digitized, “it’s probably out there, free for the taking. The old business model doesn’t work anymore. It’s hard to compete against instantaneous, plentiful and free.”

Hilary Price, whose syndicated strip “Rhymes With Orange” launched in the summer of 1995, says journalism’s digital transition has affected comics’ visibility for the worse.

“For readers who get their news on a screen, online newspapers bury their comics deep in their websites, if they carry them at all,” Price says. “Sunday funnies don’t ‘wrap’ the Sunday e-editions. So as more people migrate to the screen, the comics are further divorced from the news-reading experience.”

Breathed, who last month celebrated the 40th anniversary of “Bloom County’s” launch, says he has adjusted to the industry’s technological evolution. He revived “Bloom County” in 2015 after ending the Pulitzer Prize-winning strip in 1989.

Today, he values his “immediate relationship” with his online readers – a smaller but more connected audience than in the 1990s. “I knew nothing of, or from, my readers for decades. Now, we’re family,” Breathed says. “Not a family of 70 million anymore, but closer. We hug digitally – far more rewarding.”

The key to adapting to the new ecosystem, he says, is to keep your eyes and insights facing forward: “It’s like divorce and resenting finding your assets halved overnight: The mental Zen trick for survival is pretending that the other half never existed.”

Although the 20th century primacy of the mass-media newspaper comic strip has faded, Watterson is optimistic about the next generation.

“That makes me feel old, but comics are an incredibly versatile, adaptable art,” he says. “They’re such a natural and effective way to communicate ideas that I don’t doubt that new artists will find new ways to find new audiences.

“I have to remind myself that this internet landscape is completely normal to the kids coming up, and their motivations and solutions will not be what mine were,” he notes. “The world moves on.”

Breathed, whose Hollywood credits include adapting his book “A Wish for Wings That Work,” compares the print comic strip with the movie multiplex, believing both are in permanent repose.

“Neither movies nor comic art are disappearing, though,” he says. “That’s the punchline.”