New website imagines the Snake River without dams

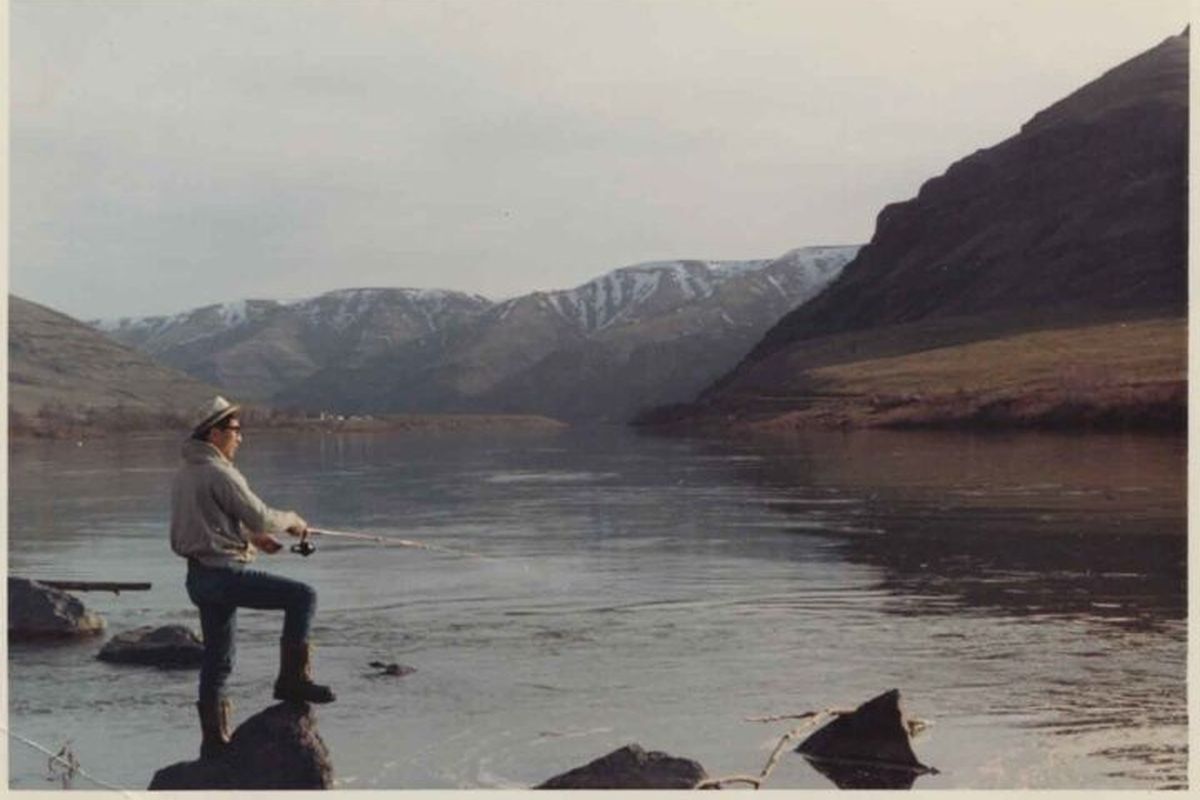

A photo of Granite Point, pre-dam from Washington State University. (Courtesy of the Laughlin Collection, WSU)

An advocacy group angling for a free-flowing Snake River has released a detailed multimedia website envisioning what the removal of four dams could mean for the region.

“We’re hoping that interactive map is a tool to show people what was there,” said Sam Mace, the Inland Northwest Director of Save Our Wild Salmon.

“The recreation values it had. The fishing opportunity. And to start that community conversation of, ‘Well if the dams come out, what could we have there again? How could a restored river best benefit Eastern Washington’s communities and its economies?’ ”

Ice Harbor Dam opened in 1962, followed by Lower Monumental Dam in 1969 and Little Goose Dam in 1970. As the water pooled behind each successive structure, it flooded 14,400 acres, washed away ancient Native American gathering sites, burial grounds, fishing holes and more towns. The dams also generated cheap electric power, allowed barges to travel deep into Washington wheat country and provided some irrigation.

The website, developed by Save Our Wild Salmon, tries to visualize what the 144-mile river looked like before all that.

It incorporates historic photos, oral and written records from people who remember the Snake River before the dam and designs from Washington State University landscape architecture students imagining what Lewiston and Clarkston’s waterfront areas could look like.

It also includes memories from folks who saw the Snake before the dam.

“There was about a period of three or four years where we quit hunting down there and I went back and the dams had been built in that meantime, and suddenly everything changed and it was just a real shock to see everything change in such a short period of time,” said Harvey Morrison, the president of Spokane Falls Chapter of Trout Unlimited in a video. “It was a phenomenal habitat for game birds and deer. They have estimates of tens of thousands of birds that we lost because of the inundation of the reservoirs.”

While there is no ignoring the divisive nature of the issue, the website and associated materials aim to sidestep, at least temporarily, thornier questions of power production, CO2 emissions, spiraling salmon populations and transportation.

“We kind of wanted a tool that wasn’t about arguing over whether the dams should stay or go but asking that ‘what if’ question,” Mace said. “And that’s important regardless of whether someone (believes) the dams should be removed. It’s in all of our best interests to start exploring that question. It’s going to be a regional decision.”

In particular, the website highlights the recreational benefits of a free-flowing Snake.

First would be salmon and steelhead angling, but rafting, kayaking, jet boating and swimming opportunities would all increase. Nearly 50 rapids were flooded between the confluence of the Snake and the Columbia and the Washington/Idaho state line.

Richard Scully, 75, was born in the Lewiston area and has spent most of his life there. He remembers biking to the river before school and dropping lines for steelhead. Now, much of the river bank, particularly around towns and communities, is filled with human-placed rock – known as riprap – to prevent erosion.

Similarly, Bryan Jones, 66, a fourth-generation wheat farmer near Colfax, remembers picking peaches at Penawawa, Washington, a town that was flooded by the rising waters.

Of course, a free-flowing Snake would destroy or greatly reduce some current recreation uses like bass fishing and river cruises. That’s a fact Save Our Wild Salmon acknowledges, although it maintains that overall recreation would increase.

“I think there is a give-and-take there,” said Kurt Miller the executive director of Northwest River Partners, a hydropower advocacy group based in Vancouver, Washington. “There would be winners and losers on the recreation side.”

He questions some studies that have predicted huge economic benefits in the form of increased recreation.

“I think those questions need to be examined more closely,” he said. “Because right now I think those studies make some really bold assumptions.”

Although the visioning project started nearly a decade ago, Mace said, a plan to breach the dams proposed by an Idaho Republican congressman has given the project new urgency.

In February, Rep. Mike Simpson released a $33 billion plan to breach four dams on the lower Snake River, replace the lost hydroelectric energy with other sources and ensure irrigation and livestock protection for agriculture industries affected by the breaches. The fate of that effort is unsure, with resistance coming from farmers, hydropower operators and others.

Either way, the website provides a glimpse into the past, and some hope, the future.

“There are old-timers who remember hunting and fishing down there, but a lot of people in the region don’t have those memories,” Mace said.