Through poetry, images and conversation: Poet and playwright Claudia Rankine to deliver Gonzaga’s Race and Racism Lecture

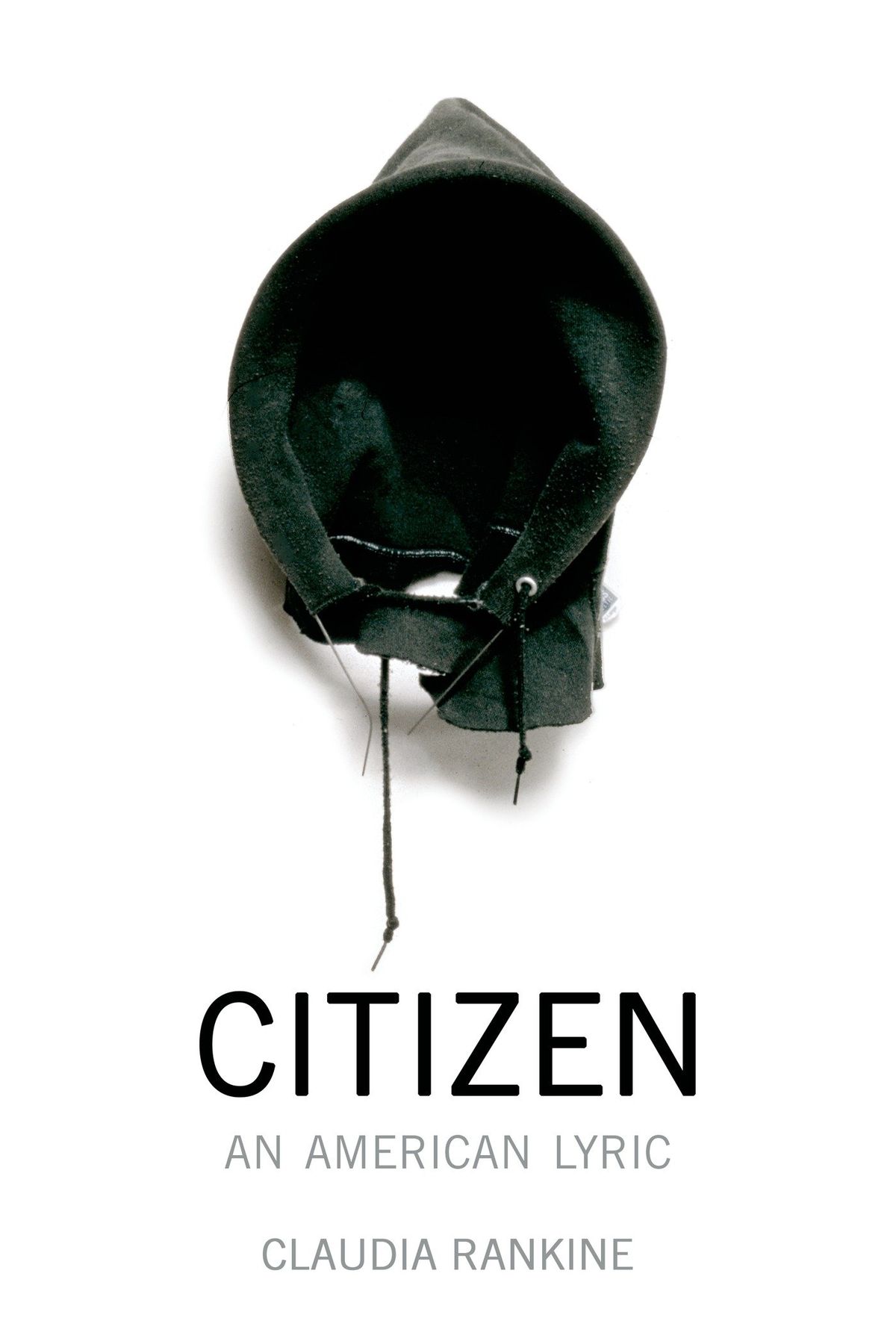

Claudia Rankine is a poet, playwright and author of “Citizen: An American Lyric.” (Courtesy)

In recent weeks, professors and students at Gonzaga University have teamed up with teachers and students in Spokane high schools to have conversations about race and racism aided by poet and playwright Claudia Rankine’s “Citizen: An American Lyric.”

Gonzaga purchased 700 copies of the book and sent a majority to area high schools.

“The high school teachers will direct the conversations to ensure the subject matter addresses their own curriculum,” Professor Brian Cooney, director of Gonzaga’s Center for Public Humanities, said in a news release.

“Each class or club is very different. One class is Advanced Placement Literature, another is African American Literature. The Rogers High School Black Student Union and North Central Creative Writing Clubs will welcome our faculty, with each section likely examining the book from a different perspective.”

These conversations will culminate with a virtual presentation by Rankine on Wednesday at 6 p.m. as part of Gonzaga’s Race and Racism Lecture.

Registration for the event is available through bit.ly/2LUofBD. Gonzaga sponsors for Rankine’s lecture include the Center for Public Humanities, Center for Civil and Human Rights at Gonzaga Law, Visiting Writers Series, the Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, the Powers Chair of Humanities, Unit Multicultural Education Center, Black Student Union and the Office of the President.

Rankine’s presentation follows Race and Racism Lecture speeches by activist, author and academic Angela Davis, critical race theorist and civil rights advocate Kimberlé Crenshaw and co-founder of the Black Lives Matter movement Patrisse Cullors.

Rankine is the author of, among many other works, “Don’t Let Me Be Lonely: An American Lyric,” “Citizen: An American Lyric” and “Just Us: An American Conversation,” a trilogy of works that examine race and racism through poetry, images and conversation.

“No, I didn’t know when I was working on ‘Don’t Let Me Be Lonely’ that I would continue down that road,” Rankine said of her 2004 release. “But, historically, we continued down the road. It was an overarching scan in ‘Don’t Let Me Be Lonely’ of the territory of grief, and I think ‘Citizen’ honed in on anti-Black violence, and ‘Just Us’ is even more honed in on white supremacy and types of that violence. … When I wrote ‘Citizen,’ I didn’t know I would write ‘Just Us.’ They just build.”

“Citizen,” which was released in 2014, won a number of awards, including the 2014 National Book Critics Circle Award for Poetry, the 2015 NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Literary Work in Poetry and the 2015 Forward Prize for Poetry Best Collection. It was nominated for many others, including the 2014 National Book Award in Poetry and the 2014 National Book Critics Circle Award in Criticism and was a New York Times bestseller.

When deciding upon the title “Citizen,” Rankine said she didn’t have a singular interpretation of the word in mind but rather was hoping people would bring to it whatever they identified with the word.

“The question was, for me, really, how do you understand the term?” she said. “Who belongs to this term? Are you a citizen by virtue of being a citizen, and who gets the rights of that, and what does that mean? I wanted the word to accordion out to all those things.”

The seven chapters in “Citizen,” which cover microaggressions Rankine has experienced, self-identity, Hurricane Katrina, stop-and-frisk, the murders of Trayvon Martin and James Craig Anderson and much more, are interspersed with photos, images of paintings and sculptures, screen grabs and other images.

Rankine included these images alongside the text because she wanted “Citizen” to be both a reading and visual experience.

“In part because so much that happens with racism gets activated when a person walks in a room, when that person is being seen,” she said. “There’s a lot of institutional policy and history that just applies to what is possible for Black and brown people and for women, but then there’s a level of regression that is activated when someone notices that you’re a Black person. Much in the same way it can get activated if you’re a woman in a company of men.”

Rankine said many of the images included in “Citizen” came to her as she was writing the book. Even still, she worked to find the line between including images that would help illustrate her point without being harmful to Black readers.

“You want images that will bring the history forward but won’t cause harm again and trigger people back into sorrow beyond what just is there,” she said.

In one image, for instance, a group of white men and women are gathered under a tree from which a lynching victim hangs, only the murdered individual has been edited out of the photo.

“Part of the reason for that was one, not to replicate violence, but also to put the emphasis on white people as the perpetrators of the violence because the spectacle of Black death can distract people from the fact that this is barbarian behavior,” Rankine said.

The final book in Rankine’s trilogy, “Just Us,” was released in September. In the book, Rankine examines the conversations she’s had with, for example, a white man in an airport who thinks his inability to “play the diversity card” is the reason his son wasn’t accepted into Yale and a white friend who remains seated when she and Rankine attend Jackie Sibblies Drury’s “Fairview,” a play during which white audience members are asked to come onstage while Black audience members stay seated.

Each person involved in one of the conversations in the book then responds to Rankine’s writing.

While both “Don’t Let Me Be Lonely” and “Citizen” share the subtitle “An American Lyric,” “Just Us” is billed as “An American Conversation.” Rankine said the decision to change subtitles had to do with the content of the work.

“In ‘Lonely’ and ‘Citizen,’ the point-of-view is really inside the experience of racism for Black and brown people, and the ‘lyric’ is the realm for that point, for that assessment,” she said. ” ‘Just Us’ creates the pedagogy around the conversation, and so I wanted to build the process toward a conversation, which is a little bit different than addressing a feeling. I’m writing it, and I do identify as a poet, so there’s poetry in there, but the structure of the book is the retelling of conversations.”

At a time when face-to-face conversations are even more difficult, Rankine believes there are pros and cons of social media becoming a primary means of discussion. On one hand, she said, it has created community and made people aware of events in a way that one-on-one conversations can’t. On the other, one-on-one conversations have a richness that social media doesn’t.

“We wouldn’t have known about certain things at the lightning speed that we do now without social media, but it still doesn’t mean we don’t wait for the facts that fill out the story and look at the various factors that impact the moment.”

Rankine’s presentation is part of Gonzaga’s Black History Month celebration, which also includes the annual William L. Davis S.J. Lecture at noon on Feb. 17. This year’s speaker is Ariela Gross, J.D., Ph.D., professor of law and history at the University of Southern California.

Gross will discuss her book “Becoming Free, Becoming Black: Race, Freedom and Law in Cuba, Virginia and Louisiana,” which tells of “enslaved and free people of color who used the law to claim freedom and citizenship while challenging slaveholders’ efforts to make Blackness synonymous with slavery,” according to the registration page.

Registration for the event is required through bit.ly/zaglawbecomingfree. Gross’s talk, which is sponsored by Gonzaga’s History Department and the Center for Human and Civil Rights, is free and open to the public.