400-acre Kaiser property in Mead, near former smelter site, slated for 1,400-residence mixed-use development

The Kaiser Aluminum smelter in Mead, shown in this March 6, 1972 photo, operated for decades in rural Spokane County before being shuttered and demolished. A new plan would lead to construction of a 400-acre mixed-use development on Kaiser property just north of the smelter. (Jack Cunningham/Spokesman-Review archives)

The developer who transformed an old industrial site near downtown Spokane into the thriving mixed-use Kendall Yards development believes he can do the same thing on a 400-acre Kaiser Aluminum site north of the city limits in Mead.

Jim Frank’s Greenstone Corp. has purchased 300 acres of the parcel and entered into a development agreement with Kaiser, which will retain ownership of the other 100 acres, to construct a walkable community that will include some 1,450 residences as well as about 1.2 million square feet of commercial space.

The development has tentatively been named Mead Works, Frank said, in “reference to the history of the site.”

That history stretches back to World War II, when the federal government opened an aluminum smelter on about 180 acres of land in what was then a rural part of Spokane County. Kaiser Aluminum and Chemical Corp. purchased the plant in 1946, and a decade or so later the company bought another 400 acres just to the north.

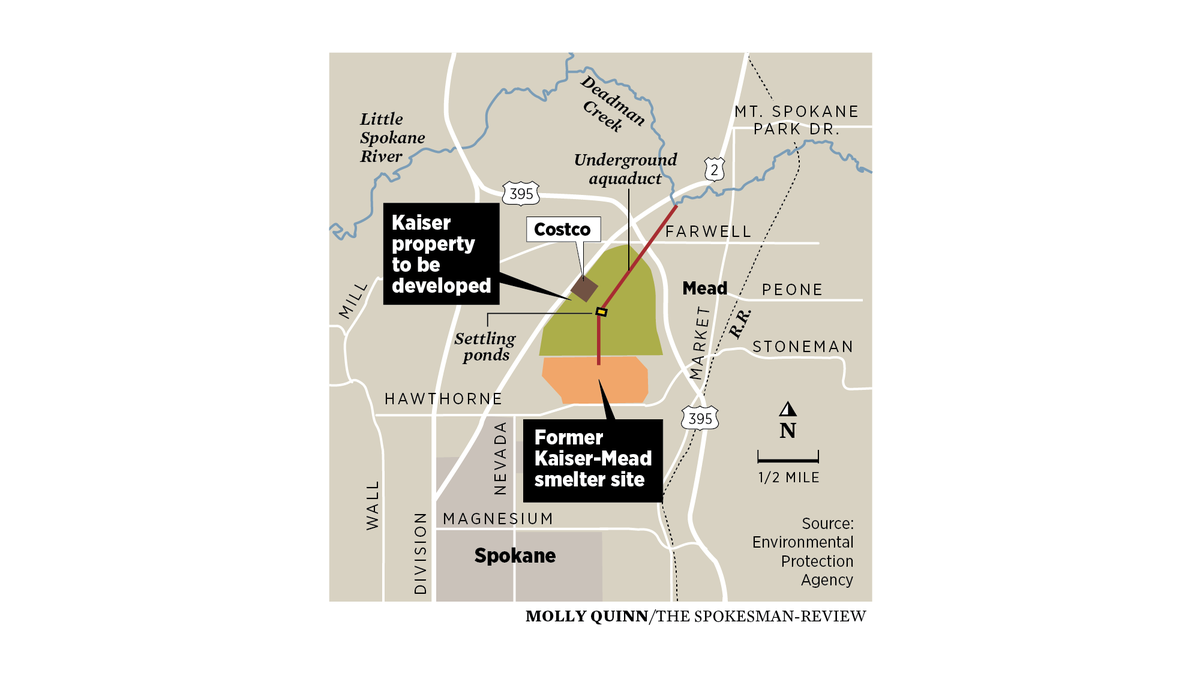

While Kaiser didn’t extensively develop that additional parcel, it did funnel heavily contaminated stormwater from the smelter site across the land, on its way to Deadman Creek. En route, however, the stormwater collected in a pair of settling ponds located near the center of the property. What settled in those ponds were, to a large degree, carcinogenic toxins known as PCBs.

This past summer, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency began working with Kaiser on a ”time-critical” cleanup of the ponds. It was a daunting job.

“There were enough PCBs in those ponds to contaminate a lake the size of Lake Coeur d’Alene times 30,” said Brooks Stanfield, an on-scene coordinator with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

And during the cleanup process, Stanfield said, crews excavating sediment from the main, lower pond discovered a potentially complicating issue: a handful of holes in the liner designed to contain the toxins.

Stanfield said the holes were relatively small – the size of a basketball or smaller – but that they may have allowed pollution to migrate out of the supposedly secure pond.

Instead of thoroughly investigating whether toxins really did migrate into the soil and the groundwater, officials decided to cover the liner with sand and put in another liner over it before returning the settling pond to use.

So while EPA and Kaiser completed work on the 400 acres now slated for development, work and testing will have to continue before construction at the site can go forward, according to Jeremy Schmidt, engineering site manager with the Washington Department of Ecology.

The first step will entail coming up with an alternative method for capturing the stormwater runoff from the smelter site, so it no longer runs across the future home of Mead Works, no longer settles in the ponds and no longer enters Deadman Creek, Schmidt said.

Once an alternative stormwater system is implemented, Schmidt said, the ponds will be decommissioned and “Kaiser or the buyers will be required to sample beneath those ponds to make sure those contaminants did not” leach through the possibly compromised liners.

The 400-acre parcel also lies just north of a Superfund site that is home to a highly toxic plume of cyanide pollution that is the subject of an ongoing, multimillion-dollar cleanup plan.

Though Frank acknowledged the need to complete the site’s remediation, he expressed confidence the cleanup questions will be overcome.

“Nothing in life is guaranteed, as we’ve found out in the pandemic,” Frank said. “But we have a lot of experience dealing with these kinds of sites.”

Kendall Yards, he noted, required “a lot of remediation” and he and his partners are “dealing with a lot of the same type of issues” at the Mead Works site. And, he added, he and his partners “feel like enough research has been done … to understand the scope of the issues and what the solutions are.”

“We’re confident that all of those will be resolved by the end of the year,” Frank said.

He also pointed to a number of advantages that the site offers, including its location just west of the North Spokane Corridor.

Frank described the project as the “first development facilitated by construction” of the long-awaited interstate-style highway that some state legislators are pushing to fast-track toward completion.

Frank said Mead Works is being “designed to really fully use the North Spokane Corridor” instead of funneling more traffic on overburdened north-south arterials like Division and Nevada streets.

He said the project will also involve the construction of a new frontage road along U.S. Highway 2, extending from Farwell Road to Hawthorne Road. The aim, Frank said, is to “provide better traffic distribution, so we’re not loading up all the traffic” on Highway 2, which forms the property’s western border.

The development, which will surround on three sides a recently constructed Costco, will also be designed to include many of the services people want and need without having to hop in their car and drive elsewhere, Frank said.

“The idea is to do something that’s higher density than your typical residential subdivision and create enough density that you can help support alternative methods of mobility,” he said.

Frank said he and his partners are aiming to create “a small, walkable town-center element” to go along with a mix of single-family homes, townhouses, small multifamily condo structures, large multifamily apartment buildings as well as an age-restricted community for people 55 and older.

“Something that’s always been very important to us is that we have economic diversity and diversity of housing types, so that you get a balanced community in terms of economic opportunity,” Frank said.

He believes demand for this kind of mixed, planned community is high right now.

“I think it’s the right time for mixed-use developments,” Frank said. “I think people really want to see more walkability, they want to see more mixed-use developments. They want to have a diverse range of house.”

Spokane County Commissioner Al French expressed excitement about the project during an unrelated Wednesday meeting, where he said the development has a “similar flavor” to the popular Kendall Yards.

Greenstone, which has also built mixed-use communities in Liberty Lake and Kootenai County, is intent on meeting the anticipated demand for its latest product as quickly as possible.

While the developers are still waiting for Spokane County to approve an amendment to its comprehensive plan that would rezone 81 acres from light industrial to mixed-use, Frank believes work on the project’s infrastructure will begin this year and that residential construction and commercial development could start next year.

When the project is complete on what is now land just north of the Spokane city limits, Frank predicted its value will be staggering.

“The total value 20 years from now of the site development will be $600, $700, $800 million dollars,” he said.

Though the project is bound to accelerate the already brisk pace of development in the area, Frank said the developers “intend on being a good neighbor” and “to communicate with all of those people” who will be affected.

Among those he has reached out to are the Mead School District, where the children of the thousands of new residents would go.

In an emailed statement, Ned Wendle, the district’s executive director of facilities and planning, said, “The school district met with the potential developer and generally discussed their plan last fall. We’ll continue to stay in contact with them as they decide what the unit mix could be so that we can understand what impact that will have on our schools. The developer shared that this project could take years to fully develop, which gives us time to plan for any increase in school age children.”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to correct the timing of Kaiser’s purchase of the aluminum plant from the U.S. government, which occurred in 1946, not in the 1960s.