David Driskell at the Phillips Collection: An artist and a scholar of African American art history

Washington Post

WASHINGTON – You might expect an exhibition featuring an artist who is better known as a historian to come with an academic bent. And on some level, painter David Driskell’s show at the Phillips Collection, “Icons of Nature and History,” does tell a story with scholarly significance.

Many art movements and influences make appearances here. In a work titled “Our Ancestors, Festival,” the faces of African tribal masks are speckled with Abstract Expressionist brushstrokes and embedded in a geometric composition that suggests hard-edge abstraction. In “Behold Thy Son,” Driskell renders Emmett Till in a byzantine, Christ-like pose, bestowing the Black teenager, lynched in 1955, with a kind of ecclesiastical regard. Engaging a wide range of genres – still lives, portraits, abstraction, landscape – Driskell seems to appear in the show with his academic background on full display.

But Driskell ultimately ditches the textbook, engaging categories to collapse them. When he takes to painting something – fruit in a bowl, an abstracted tree, an African deity – he doesn’t do it pro forma. He brings extra verve, something personal.

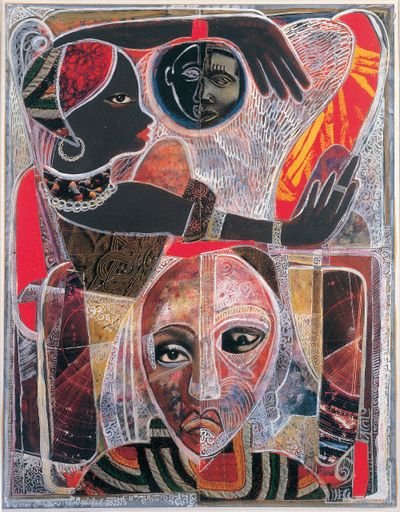

In “Still Life with Sunset,” for instance, a flat horizon line seems to bring its subject (a bowl on a table) impossibly close to a bright red sun, inflecting ordinary household objects with the cosmic, and bringing the divine to the dinner table. His portraits, such as “Self-Portrait as Beni(“I Dream Again of Benin”) ” and “Memories of a Distant Past,” have rifts that divide the faces in half, creating a kind ofdouble portrait with an African masklike visageon one side and a realistic face on the other. It’s as if, in the world of his art, masks and duality are a truth – what appears singular or simple, a lie.

Celebrated for establishing African American art history as a formal field of study, Driskell, who died in 2020, curated the landmark 1976 show “Two Centuries of Black American Art,” at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Chronicling our nation’s overlooked history of Black art from 1750 to 1950, he included work across mediums from such artists as Civil-War era landscape painter Robert S. Duncanson; Harlem Renaissance sculptor Selma Burke; and designer and watercolorist Lois Mailou Jones, who taught Driskell at Howard in the 1950s. Today, a center for the study of African American visual art and culture is named after Driskell at the University of Maryland, where he taught from 1977 to 1998.

Informed by his studies at Skowhegan – the artist retreat in Maine, near where he’d later establish a studio – Driskell explored natural imagery, including the pine tree, a lifelong motif. Trips to Africa fueled his desire to keep African cultural symbols alive in his work, which includes homages to artists Jacob Lawrence and Romare Bearden. This well-studied perspective comes through in such works as “Frost and Ice, Maine,” in which the artist takes on the short, staccato-brushstroke style of Alma Thomas, a friend he met in D.C. (and the subject of her own Philips Collection show “Everything is Beautiful,” on view upstairs through Jan. 23). You can see both the art historian and artist in action – wrapping his head and hand around another’s distinctive style, while simultaneously crafting his own.

In presenting Driskell as an artist, the Phillips Collection foregrounds his range. The first gallery in the show includes a religious painting, an mixed-media assemblage and an abstraction. But there’s more to these works than checking boxes.

Driskell’s late father, a minister who, as Driskell recalled, liked to doodle images of angels, lives on in the sublime, winged figure floating above a church in “Let the Church Roll On.” The assemblage “Gate Leg Table” features a worn piece of wood – part of a chair – that reads like a faded memory of Driskell’s grandfather, a furniture maker. “Young Pines Growing” reflects pine trees native to the artist’s home state of North Carolina, as well as Maine, where he lived part of the year.

If most cubism breaks down an object to its various perspectives, Driskell’s “Young Pines Growing” seems to break down time itself. The green paint blurs, spilling out over long, linear branches, as if we are watching the needles fill in and the tree pass through time – months, years – at the speed of a whizzing car. It’s a symbol he returns to repeatedly, fitfully, restlessly, as if acutely aware of the ever-present, subtle motion of a living thing that stands tall, year-round, defiant of season and struggle.

During Driskell’s career, much of the art world (New York-centric, predominantly White) was resisting figuration and disavowing personal narrative for what was believed, perhaps naively, to be a universal, apolitical language of abstract form.

Driskell’s early paintings, “City Quartet” and “Boy with Birds,” which are poignantly paired in the show, have a vulnerability and a narrative feel. In the latter image, a young Driskell appearsto be almost physically a part of the New York cityscape, conveying a full-body yearning to be one with the place. In his later work, Driskell infused the abstract with quiet sentimentality, evoking his mother, a quilt maker, in strip-quilt canvases with detailed, ornamental patterns. On view in the show’s final gallery, they ring like the subdued high point of a subtle crescendo.

Everything in “Icons,” in some way, feels like a collage – of transcontinental longings, tactile memories and academic insights. Woven together with threads from a childhood surrounded by makers, Driskell’s work reflects a lifetime spent studying artists and more crucially, being one among them.