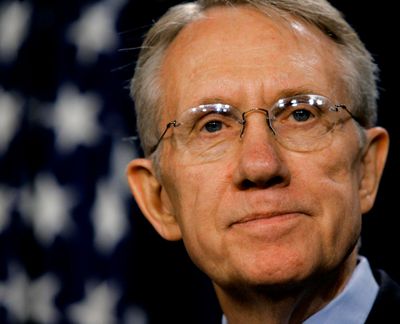

Harry Reid, former Senate majority leader, dies at 82

LAS VEGAS – Harry Reid, the former Senate majority leader and Nevada’s longest-serving member of Congress, has died. He was 82.

Reid died Tuesday, “peacefully” and surrounded by friends “following a courageous, four-year battle with pancreatic cancer,” Landra Reid said of her husband in a statement.

“Harry was a devout family man and deeply loyal friend,” she said. “We greatly appreciate the outpouring of support from so many over these past few years. We are especially grateful for the doctors and nurses that cared for him. Please know that meant the world to him.”

Funeral arrangements would be announced in coming days, she said.

The combative former boxer-turned-lawyer was widely-acknowledged as one of the toughest dealmakers in Congress, a conservative Democrat in an increasingly polarized chamber who vexed lawmakers of both parties with a brusque manner and this motto:

“I would rather dance than fight, but I know how to fight.”

Over a 34-year career in Washington, Reid thrived on behind-the-scenes wrangling and kept the Senate controlled by his party through two presidents – Republican George W. Bush and Democrat Barack Obama – a crippling recession and the Republican takeover of the House after the 2010 elections.

He retired in 2016 after an accident left him blind in one eye.

Reid in May 2018 revealed he’d been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and was undergoing treatment.

Less than two weeks ago, officials and one of his sons, Rory Reid, marked the renaming of the busy Las Vegas airport as Harry Reid International Airport. Rory Reid is a former Clark County Commission chairman and Democratic Nevada gubernatorial candidate.

Neither Harry nor Landra Reid attended the Dec. 14 ceremony held at the facility that had been known since 1948 as McCarran International Airport, after a former U.S. senator from Nevada, Pat McCarran, and today ranks as one of the 10 busiest airports in the U.S.

He was known in Washington for his abrupt style, typified by his habit of unceremoniously hanging up the phone without saying goodbye.

“Even when I was president, he would hang up on me,” Obama said in a 2019 tribute video to Reid.

He was frequently underestimated, most recently in the 2010 elections when he looked like the underdog to tea party favorite Sharron Angle. Ambitious Democrats, assuming his defeat, began angling for his leadership post. But Reid defeated Angle, 50% to 45%, and returned to the pinnacle of his power. For Reid, it was legacy time.

“I don’t have people saying ‘he’s the greatest speaker,’ ‘he’s handsome,’ ‘he’s a man about town,’ ” Reid told the New York Times in December that year. “But I don’t really care. I feel very comfortable with my place in history.”

Born in Searchlight, Nevada, to an alcoholic father who killed himself at 58 and a mother who served as a laundress in a bordello, Reid grew up in a small cabin without indoor plumbing and swam with other children at a pool at a local brothel. He hitchhiked to Basic High School in Henderson, Nevada, 40 miles from home, where he met the wife he would marry in 1959, Landra Gould. At Utah State University, the couple became members of The Church of Latter-day Saints.

The future senator put himself through George Washington University law school by working nights as a U.S. Capitol police officer.

At age 28, Reid was elected to the Nevada Assembly and at age 30 became the youngest lieutenant governor in Nevada history as Gov. Mike O’Callaghan’s running mate in 1970.

Elected to the U.S. House in 1982, Reid served in Congress longer than anyone else in Nevada history. He narrowly avoided defeat in a 1998 Senate race when he held off Republican John Ensign, then a House member, by 428 votes in a recount that stretched into January.

After his election as Senate majority leader in 2007, he was credited with putting Nevada on the political map by pushing to move the state’s caucuses to February, at the start of presidential nominating season. That forced each national party to pour resources into a state which, while home to the country’s fastest growth over the past two decades, still only had six votes in the Electoral College. Reid’s extensive network of campaign workers and volunteers twice helped deliver the state for Obama.

Obama in 2016 lauded Reid for his work in the Senate, declaring, “I could not have accomplished what I accomplished without him being at my side.”

The most influential politician in Nevada for more than a decade, Reid steered hundreds of millions of dollars to the state and was credited with almost single-handedly blocking construction of a nuclear waste storage facility at Yucca Mountain outside Las Vegas. He often went out of his way to defend social programs that make easy political targets, calling Social Security “one of the great government programs in history.

Reid championed suicide prevention, often telling the story of his father, a hard-rock miner who took his own life. He stirred controversy in 2010 when he said in a speech on the floor of the Nevada legislature it was time to end legal prostitution in the state.

Reid’s political moderation meant he was never politically secure in his home state, or entirely trusted in the increasingly polarized Senate. Democrats grumbled about his votes for a ban on so-called partial-birth abortion and the Iraq war resolution in 2002, something Reid later said it was his biggest regret in Congress.

He voted against most gun control bills and in 2013 after the Sandy Hook Elementary School massacre, dropped a proposed ban on assault weapons from the Democrats’ gun control legislation. The package, he said, would not pass with the ban attached.

Reid’s Senate particularly chafed members of the House, both Republicans and Democrats. When then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, a Democrat, muscled Obama’s health care overhaul through the House in 2009, a different version passed the Senate and the reconciliation process floundered long enough for Republicans to turn it into an election-year weapon they used to demonize the California Democrat and cast the legislation as a big-government power grab. Obama signed the measure into law in March 2010. But angered by the recession and inspired by the small-government tea party, voters the next year swept Democrats from the House majority.

Reid handpicked a Democratic candidate who won the election to replace him in 2016, former Nevada Attorney General Catherine Cortez Masto, and built a political machine in the state that helped Democrats win a series of key elections in 2016 and 2018.

On his way out of office, he repeatedly lambasted Donald Trump, calling him at one point “a sociopath” and “a sexual predator who lost the popular vote and fueled his campaign with bigotry and hate.”

Reid, after all, had faced one of those before he ever got to Washington. Then head of the Nevada Gaming Commission investigating organized crime, Reid became the target of a car bomb in 1980. Police called it an attempted homicide. Reid blamed Jack Gordon, who went to prison for trying to bribe him in a sting operation Reid participated in over illegal efforts to bring new games to casinos in 1978.

Following Reid’s lengthy farewell address on the Senate floor in 2016, his Nevada colleague Republican Dean Heller declared: “It’s been said that it’s better to be feared than loved, if you cannot be both. And as me and my colleagues here today and those in the gallery probably agree with me, no individual in American politics embodies that sentiment today more than my colleague from Nevada, Harry Mason Reid.”