‘White Christmas’ was the song America needed to fight fascism

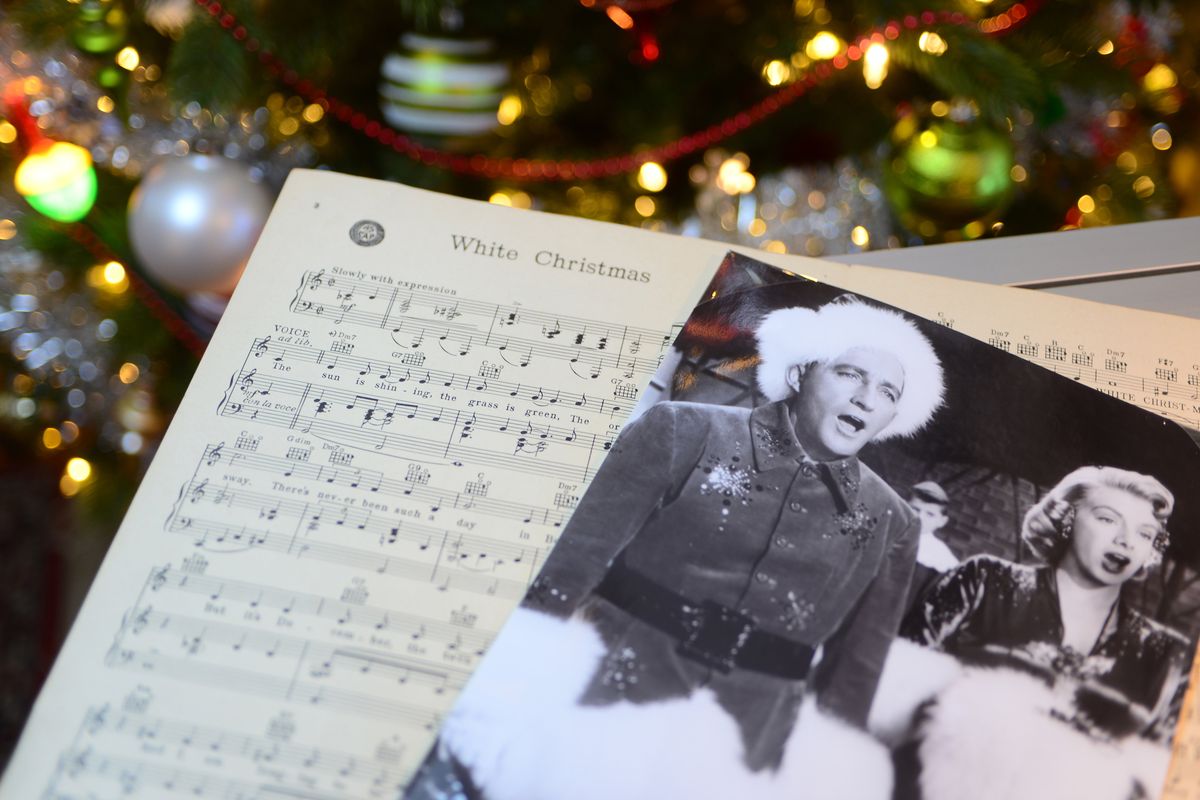

On Christmas Day 1941, crooner Bing Crosby stepped up to the microphone to introduce his new song. He was performing live on his hugely popular national radio show on NBC, “Kraft Music Hall.”

As the orchestra began to play, Crosby’s calming baritone floated over the airwaves: “I’m dreaming of a white Christmas, just like the ones I used to know …”

He ended the wistful song of holidays past, and the audience politely clapped. It was the first time he had sung “White Christmas” – what would become Irving Berlin’s super seasonal classic – but hardly anyone noticed it then.

The United States, still numb from the devastating attack on Pearl Harbor a little more than two weeks earlier, was preparing for a deadly war and had little time for a sentimental song about “sleigh bells in the snow” and “merry and bright” days.

“America was massively distracted,” said James Kaplan, author of “Irving Berlin: New York Genius,” published in 2019. “This was only 17 days after the worst attack on the country ever. There were more pressing concerns at the time.”

Of course, “White Christmas” would become the biggest-selling single of all time. According to Guinness World Records, it has sold some 50 million copies worldwide, with another 50 million in album sales.

So how did “White Christmas” become the megahit it is today?

Oddly, the very circumstances that inhibited its initial success eventually led to its explosion. As young men went off to face fascism and tyranny in faraway killing fields, the song’s touching message would resurface as a symbol of longing for a life that once was.

“White Christmas” was the brainchild of one on America’s greatest songwriters. Born Israel Beilin in western Siberia in 1888, Irving Berlin grew up on the mean streets of the Lower East Side of New York City. As a child, this son of an Orthodox rabbi learned about Christmas from an equally poor Irish Catholic family, the O’Haras. Young Izzy, as his childhood companions called him, was welcomed into their home, where they introduced him to what could best be described as a Charlie Brown tree. It left a lasting impression.

“This was my first sight of a Christmas tree,” Berlin told the Washington Post in 1954. “The O’Haras were very poor and later, as I grew used to their annual tree, I realized they had to buy one with broken branches and small height, but to me that first tree seemed to tower to heaven.”

Later, after incredible success as a writer of the American songbook, Berlin turned his attention back to those days to compose “White Christmas.” According to Kaplan, he probably tinkered with the idea for years before inspiration struck in early January 1940, when he said to his secretary, “I want you to take down a song I wrote over the weekend. Not only is it the best song I ever wrote, it’s the best song anybody ever wrote.”

Berlin later said he intended to use “White Christmas” in a revue he planned to produce, but then decided to hold it for the movie “Holiday Inn,” which starred Crosby and Fred Astaire. That film, about a couple of country inn owners who put on musicals for each holiday, spawned several Berlin hits, including “Easter Parade,” “Happy Holiday” and “Be Careful, It’s My Heart.”

Production for “Holiday Inn” was underway in 1941 when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. Backed up by the Music Maids, Crosby introduced “White Christmas” on his national radio show on Christmas Day, but it barely made a dent in the public consciousness at the time.

In July 1942, the crooner recorded the song with an orchestra and his trademark whistling accompaniment. The movie was released the following month, and all of a sudden, the world took notice. “White Christmas” reached No. 1 on the charts in October 1942 and stayed there for 11 weeks.

For the many young men away at war, the song hit home. The early days of World War II were not good for the United States. Beginning with Pearl Harbor, the country suffered a string of defeats in the first few months of combat. Morale was low, and people needed something to hold onto. “White Christmas” and “Holiday Inn” became a lifeline for many Americans – especially overseas servicemen who heard it played on the Armed Services Radio Network.

Kaplan compared the power of the song and movie to another major media event that took the world by storm: the appearance of the Beatles on the Ed Sullivan Show in February 1964 – less than three months after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

“The country was plunged into darkness after JFK’s death, followed by this bolt of sunshine on television,” he said. “There was something about this movie and this song that had a very similar effect on America in 1942.”

The Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Carl Sandburg understood what was happening. On the first anniversary of Pearl Harbor in 1942, he wrote about “White Christmas” in the Chicago Times:

“Away down under, this latest hit of Irving Berlin catches us where we love peace. The Nazi theory and doctrine that man in his blood is naturally warlike, so much so that he should call war a blessing, we don’t like it. … The hopes and prayers are that we will see the beginnings of a hundred years of white Christmases – with no blood-spots of needless agony and death on the snow.”

When the Armed Forces Radio Network began playing “White Christmas” in 1942, servicemen couldn’t get enough of it. The military’s broadcast service was flooded with requests to play the song. The image of snow making “treetops glisten” comforted those homesick young men as they fought and died in the deserts of North Africa and the jungles of the South Pacific.

In November 1942, Time Magazine reported that “White Christmas” had sold an astounding 600,000 records in just 10 weeks. It would also be played overseas on tens of thousands of V-discs – the small metal “victory” records listened to by troops as they ducked shells and bullets in their shelters on the front lines.

“White Christmas” became an essential part of Crosby’s repertoire. He sang it often, including when entertaining the troops on USO shows in Europe and the Pacific. Later in the war, though, the crooner tried to eliminate it from the lineup – not because he didn’t like it but because he thought it sad for servicemen to hear so far from home.

Howard Crosby, the singer’s nephew, spoke with his uncle about the song’s impact, especially with the troops. In 2016, he told The Spokesman-Review:

“In December 1944, he was in a USO show with Bob Hope and the Andrews Sisters in northern France. … He had to stand there and sing ‘White Christmas’ with 100,000 G.I.s in tears without breaking down himself. Of course, a lot of those boys were killed in the Battle of the Bulge a few days later.”

Crosby’s 1942 recording of “White Christmas” has stood the test of time. Not only did it become a hit again in 1954 with the movie of the same name – starring the crooner alongside Danny Kaye, Rosemary Clooney and Vera-Ellen – it still survives today as a staple on holiday playlists for radio stations, cable music channels and satellite services.

According to Kaplan, “White Christmas” has a potency that allows it to be enjoyed by succeeding generations and even among people of different faiths. The lyrics are powerful enough to convey strong feelings of home and family, yet simple enough so everyone – Christians, Jews, atheists and others – can believe in this vision of life and longing.

“’White Christmas’ appeals universally,” Kaplan said. “It is a great and timeless song. There is something so enigmatic and withheld about it that makes it one of the great works of popular art. Ultimately, ‘White Christmas’ is a dream. This is not reality he is positing on. He’s dreaming of a white Christmas. The images are very vivid and dreamlike.”

And it was just what the United States needed in the depth of war in 1942.