‘Truly a miracle’: Ex-Cougar Dan Doornink’s family grateful after he nearly died from COVID-19 battle

SEATTLE – For the better part of three weeks, ahead of another 14- or 15-hour day sitting inside Yakima Valley Memorial Hospital, Sharon Doornink would wake up early at her Yakima home and pack herself a light lunch – half a peanut butter sandwich and an apple most days.

That was enough to sustain her through the darkest days of her husband’s prolonged fight with COVID-19. That, and prayer.

“Lots and lots of prayer,” Sharon said.

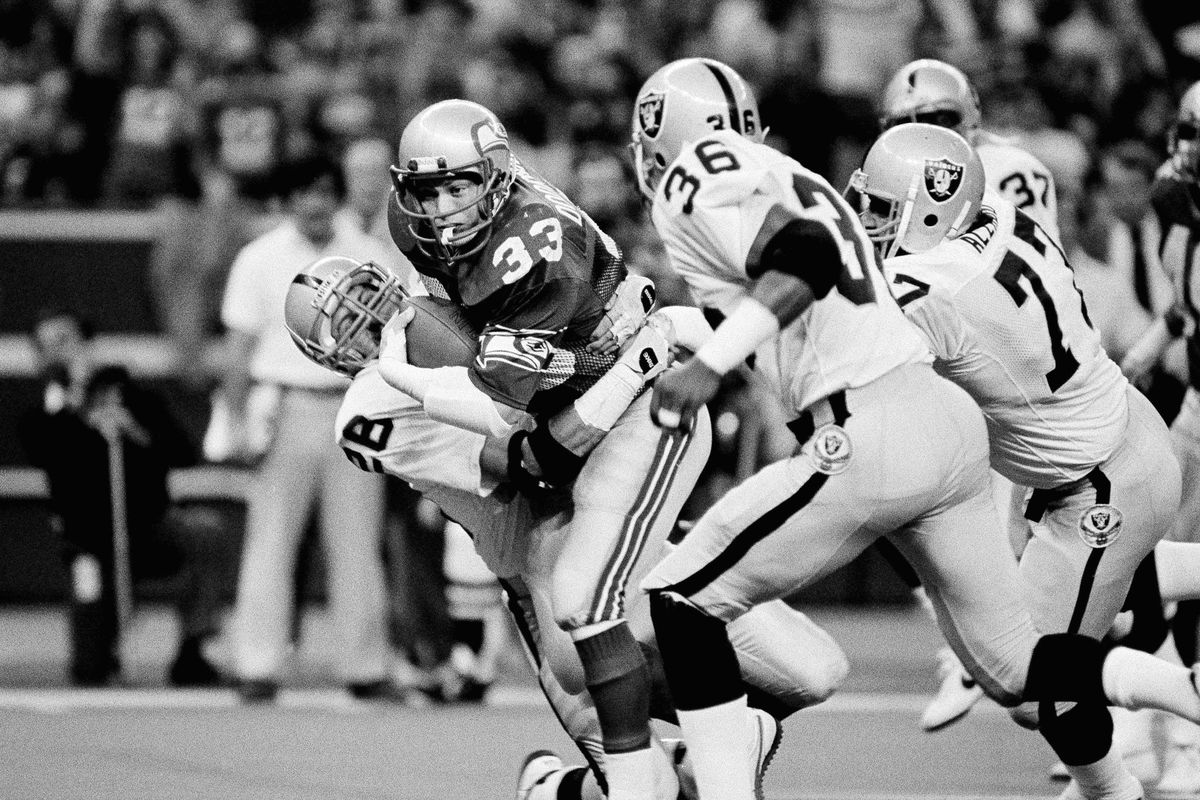

There was one scripture she recited from memory to her husband, Dr. Dan Doornink, the Washington State University Hall of Fame running back and a stalwart Seahawks player in the 1980s, as he lay unconscious in intensive care. The verse, from Proverbs 3 (“Trust in the Lord with all your heart …”), had helped bring the couple together shortly after they met in biology class at Wapato (Washington) High School. Sharon was 14; Dan was 15.

He gifted her a Bible and scribbled that verse on the inside cover. They’ve been practically inseparable in the 50 years since.

Now Sharon was repeating the prayer aloud, hoping it might bring Dan some strength in what doctors kept telling her would be their final moments together.

They had been through so much together already, one little miracle after another, as Sharon saw it. She had supported him and raised their four children during his eight-year NFL career. He spent his final few seasons with the Seahawks simultaneously attending medical school at the University of Washington, going to class in the morning, working out with the team in the afternoon and staying up late to study medical texts, asleep at 1 a.m. most nights, up again by 5.

It was never enough for Dan to simply succeed at whatever he was doing.

“He had to crush it,” his son, Tyler, said.

Which is part of what made his dire prognosis in the hospital so hard to fathom for his family. Here was this retired NFL running back, 6-foot-3 and 210 pounds in his playing days, a guy who was squatting 650 pounds in his heyday – he was Superman to his kids – now unable to breathe on his own. He was wilting away over the course of 23 days in intensive care, losing 38 pounds and just about all sense of self.

In August, Dan’s illness brought everyone back home. The couple’s four grown kids and five grandkids huddled at the family home in Yakima. Like his father, his grandfather and uncle before him, Tyler became a physician, and he flew up from Southern California, trading shifts with Sharon at the hospital.

Tyler, at his dad’s request, was mowing the lawn at his parents’ home when Sharon called with news they had been hoping to avoid: Dan needed to be intubated. She gave the phone to Dan so he could say goodbye to his son.

“This is it. I’m going to die,” Tyler remembers his dad telling him.

Although Dan was vaccinated, he had a rare blood disorder that made his treatment for COVID-19 difficult. At various points, his blood platelet level had, in layman’s terms, hit rock bottom, and he was in danger of spontaneously bleeding at any moment.

Doctors told Sharon twice they did not expect Dan to make it through the night. Even Dan’s older brother, Dave, an internist who practiced medicine with Dan for years, looked at the X-ray of his brother’s chest and came to the matter-of-fact conclusion: He’s going to die.

Despite the complications with the blood disorder, Dan did survive after five days on a ventilator. His hands had to be tied to the bed to prevent him from pulling out the tube in his throat, he was sedated much of the time, and there was still concern about his blood clotting. But he had survived the worst of it.

“Truly a miracle,” Sharon said.

•••

Early in 2020, Dr. Dan, as he’s affectionately known around town, had committed to spend his last year before retirement working at the Yakima Valley Farm Workers Clinic. Once the pandemic hit, he met regularly with patients on video calls, and estimates he diagnosed 300 cases of COVID in 10 months, before he retired three days before his 65th birthday on Feb. 1.

The pandemic had rocked the Yakima Valley and its food-processing facilities. By early summer 2020, the per capita COVID cases reached about 1,000 per 100,000 residents in Yakima County, nearly quadruple the statewide average. At one point, Yakima County represented 22% of the state’s hospitalized COVID patients and 24% of all ventilated patients, the highest rate of any county in the state.

“That was a very, very difficult time,” Dan said.

Dan and Sharon contracted the virus in August. How, exactly, they’re not sure, but they had both been vaccinated and said they had been wearing masks in public, knowing Dan’s blood disorder could (and would) complicate things if he got the virus.

Sharon was sick for a few days, but otherwise said she had mild symptoms. Once they realized Dan needed to be admitted to the hospital on Aug. 22, doctors there told Sharon he was the only COVID patient – of the 58 in their care – who had been vaccinated. The hospital was “maxed out” with patients at the time, Sharon was told.

According to Yakima County records, 27 residents died from COVID in August (of 226 reported cases at county hospitals), and 65 died in September (of 240 reported cases), more than any other month this year.

As Dan’s symptoms worsened and his breathing became more difficult, the trick for doctors was managing his blood platelets. That proved troublesome on several fronts, namely because there were no records anywhere of a patient with his blood disease having COVID – meaning there was no blueprint for how to treat him.

Dan also needed a blood transfusion, which introduces new risks for intubated patients, but no match blood could be found in Washington. Eventually, doctors found a match in Portland that was close enough to Dan’s blood type, and he ended up having three transfusions.

When things still weren’t getting better, Tyler was able to track down a cellphone number for Dr. David Garcia, an associate director of Anti-Thrombotic Therapy at UW Medical Center. Dr. Garcia, on vacation when Tyler called, recommended that Dan be given his regular blood thinner again and a double dose of steroids. That helped turn the corner.

All the while, in hopes to lifting Dan’s spirits, his kids and grandkids sent regular videos and messages, calling on FaceTime and singing to him some of his favorite songs. While Dan was still intubated, Tyler would call up a recording of the WSU fight song on his phone and hold it up to his dad’s ear.

Between prayers, Sharon would read to him. She would sing to him. She would play him music. “Crazy little things you do when you love somebody,” she said.

After five days on the ventilator, Dan was able to breathe almost completely his own, surprising his doctors with how quickly he was progressing.

“They were amazed. They were in shock, really,” Sharon said.

As word spread about his condition, messages of support poured in from all parts of the country.

“From all over the world,” Sharon said, noting friends from Christian missionaries reached out to offer encouragement.

Former teammates from WSU and the Seahawks that Dan hadn’t heard from in decades called, emailed or sent videos messages. Their encouragement took on the tone of a pregame locker-room speech.

“He would cry watching every one of those videos,” Tyler said.

•••

A few more tears were expected Thursday.

The Doorninks are together again this week, gathered in Spokane to celebrate Christmas – and the wedding of Sharon and Dan’s daughter Danielle.

In his first days out of the hospital, Dan barely had the strength to walk even a few feet on his own. He needed help getting dressed and going to the bathroom.

Three months later, he was eagerly anticipating every father-of-the-bride step down the aisle with Danielle on Thursday.

“And Danielle is very happy to have her daddy walk her down the aisle,” Sharon said. (Danielle, an elementary school teacher in Spokane, is marrying LaPhonso Ellis Jr., the son of longtime NBA player LaPhonso Ellis.

“We’re bringing the NFL and NBA families together,” Sharon said.)

As a physical medicine and rehabilitation physician, Tyler works closely with patients who have recently come off ventilators. He said he’s never “seen anything quite like” the progress his dad has made the past few months. Dan, certainly, has benefited from having a son who specializes in such a recovery, and Tyler said his dad’s vaccination status was a definite factor in his turnaround at the hospital.

But more than anything, Dan’s family points to his relentless work ethic. He’s almost maniacal about exercising. After 104 games in the NFL (and 3,842 yards from scrimmage and 26 touchdowns), he always remained active, racing mountain bikes and lifting weights into his 60s.

It hasn’t been enough for Dan to get back on his feet. He has to crush it.

He’s regained about half the weight he lost in the hospital. He still has some numbness in his thighs, but he never misses a day on his rowing machine, rowing 5,000 meters every evening, plus a workout on his stationary bike. He’s golfing at least once a week, and he’s lifting some, benching only a little more than the 45-pound bar so far (“Oh, I’d be a little embarrassed if anyone saw that,” he said.)

Dan’s cognitive functions are mostly back to normal. He still slurs his speech some, but that’s improved immensely. After weeks of struggling to whistle or sing – his favorite thing – he jubilantly emerged from his room one day singing as loud as he could, much to Sharon’s delight.

“I would listen to music, but I couldn’t make any sound come out,” he said. “Then all of a sudden I woke up – it was a Thursday – and I said, ‘Hey, I can do this!’ ”

“Boy,” Sharon added, “it does affect your brain. It really is a brain disease in a lot of ways.”

Sharon and Dan have resumed leading a youth Bible study group in Wapato, and a major breakthrough for Dan came in early November when he was finally able to ride his Craftsman lawnmower. He’s quite particular about his lawn on their 1.7-acre property, and he likes to mow every four days.

As they begin to plan for what’s next, for what retirement might bring after Dan’s recovery is complete, the Doorninks have considered selling their home and moving to Spokane, to be closer to family.

“So, yes, we are grateful for so much,” Sharon said. “Very grateful.”