‘A series of broken promises’: How the Spokane VA became testing ground for new health record system

Mann-Grandstaff VA Medical Center is pictured. (COLIN MULVANY/THE SPOKESMAN-REVIEW)Buy a print of this photo

In October 2018, the new head of the Department of Veterans Affairs told a crowd at Fairchild Air Force Base that Washington state would play an important role in the future of veterans’ health care.

Because of the state’s “perfect mix of active duty, technical infrastructure, rural components and a large number of veterans,” then-VA Secretary Robert Wilkie said, VA hospitals in Spokane, Seattle and American Lake near Tacoma would be the pilot sites for a new electronic health record system, software health care workers use to coordinate care and track patients’ medical histories, test results, medications and other information.

“We are going to test it here in Spokane,” Wilkie said. “That will be the template for the entire country.”

More than a year after that test began in October 2020, a Spokesman-Review investigation found problems with the system continue to threaten patient safety and have left employees at Mann-Grandstaff VA Medical Center in Spokane exhausted and demoralized with nearly two-thirds saying in a recent internal survey it has made them consider quitting.

While VA leaders say they remain committed to the program to replace their existing system with one developed by Cerner Corp. under a $10 billion contract, two former senior VA officials say the effort is likely to end in failure – or, at best, massive cost overruns and a system that hampers health care workers.

Facing rising cases of COVID-19 in the summer of 2020, VA’s Puget Sound facilities opted out of testing the Cerner system, which then-President Donald Trump promised in June 2017 would mean “faster, better and far better quality care” for the 28,000 veterans who rely on Mann-Grandstaff and its outpatient clinics in Coeur d’Alene, Sandpoint, Wenatchee and Libby, Montana.

Despite twice delaying the rollout, VA launched the system in the Inland Northwest just as COVID-19 cases began to increase again at the end of 2020. The result was delayed care, veterans missing important medications and a system that regularly freezes and crashes, according to reports from federal oversight agencies, the results of a “strategic review” VA sent to Congress in July and more than 40 interviews The Spokesman-Review conducted with veterans and current and former Mann-Grandstaff employees.

After pausing the system’s deployment to other sites earlier this year, VA leaders have said rollout will only occur once each new facility is ready and its staff have trained in a simulated “sandbox” environment that doesn’t involve real patients. In response to questions from The Spokesman-Review, VA Press Secretary Terrence Hayes said the department is working with Cerner to resolve the problems but does not plan to have Mann-Grandstaff revert to the old system, which every other VA facility still uses, in the meantime.

The story of the Cerner system, like the stories of the veterans it affects, starts not at VA but in the military.

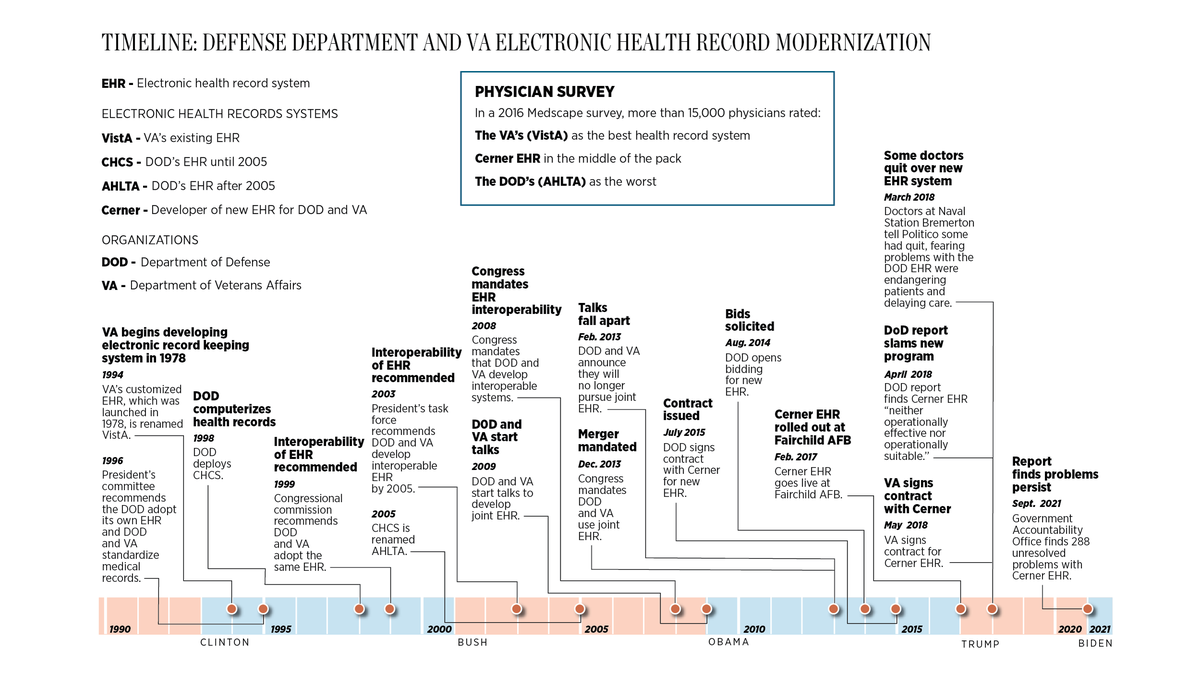

In 1996, an advisory committee set up by President Bill Clinton recommended the Department of Defense develop “a mechanism for computerizing medical data” and said the Pentagon and VA “should adopt standardized record-keeping to ensure continuity.”

At the time, VA was already using an electronic health record system, VistA, it had developed in-house and launched in 1978. Meanwhile, the Defense Department was using a separate system, later renamed AHLTA.

While AHLTA’s users have long derided the system as clunky and unstable, VistA has been customized through decades of feedback from VA employees and remains popular with users. In a 2016 Medscape survey, more than 15,000 physicians rated VistA’s patient record module, CPRS, as the best health record system and AHLTA as the worst, while Cerner’s was in the middle of the pack.

In 2008, Congress mandated that the VA and Defense Department develop health record systems with “full interoperability,” able to exchange information easily, and set up an office to coordinate that effort.

“The goal there was for DOD and VA to agree upon an electronic health record system that they could both run,” said Roger Baker, who served as VA’s chief information officer from 2009 to 2013 and was the department’s point person in the effort to align its system with the Defense Department’s.

“Our view at VA was that because of all the complexities of government medical care, the VistA system was the logical place to end up, and DOD’s view was that VistA was absolutely unacceptable,” Baker said. “We wrestled through that for three years, and that’s why the program failed in the end.”

While VistA is in the public domain and costs nothing to license, the Defense Department opted to buy a commercial health record system. The two departments announced in 2013 they would no longer pursue a shared system. Later that year, an exasperated Congress – whose members control federal spending – mandated that the Defense Department and VA implement systems with an “integrated display of data, or a single electronic health record.”

After an open bidding process, the Pentagon awarded a $4.3 billion contract in 2015 to a group of companies including Cerner, which beat out a bid from the industry’s leading health care software company, Epic Systems.

In a survey of health care providers released in July by KLAS Research, 94% of Epic users said they were satisfied with the system and 63% reported it was highly interoperable with other systems, the Defense Department’s stated top priority. Meanwhile, 62% of Cerner users said they were satisfied, and just 28% reported good interoperability.

But Baker, who served on a Cerner advisory board from 2017 to 2018, emphasized that Cerner has had success in other hospital systems. He said Cerner’s offers improvements over the Pentagon’s existing system: a combination of AHLTA and a separate platform for inpatient care called Essentris.

The Defense Department launched the Cerner system at Fairchild Air Force Base outside Spokane in February 2017, followed by deployments at bases in Western Washington months later. Soon after, reports emerged of the same problems now plaguing Mann-Grandstaff: missing prescriptions, lost referrals, the system frequently crashing and routine processes taking far longer than before.

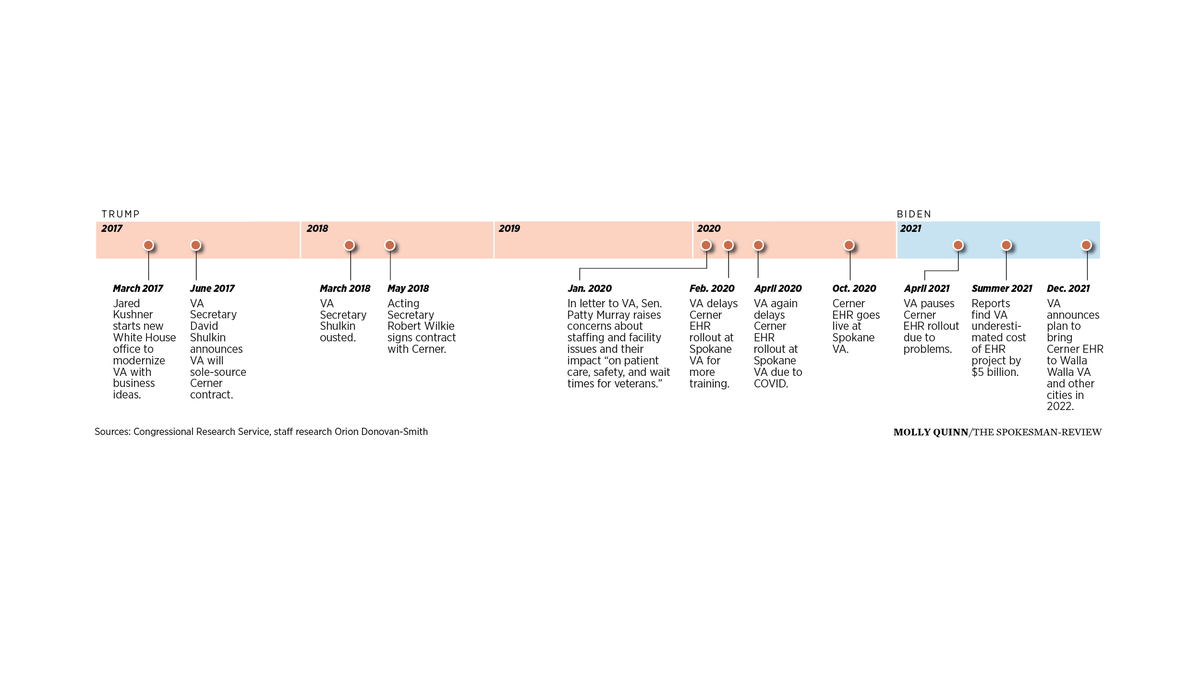

A month after the Cerner launch at Fairchild, Trump put his son-in-law Jared Kushner in charge of a new White House office that aimed to infuse government with business ideas, starting with VA. In audio leaked later that year, Kushner said he had asked Pentagon and VA officials to come up with a solution to long delays in transferring service members’ medical records to the VA when they retire from the military.

The officials, Kushner said in the recording, “came back in two weeks with something that made a lot of sense.” Their solution was to award a contract to Cerner to adopt the same system as the Defense Department, bypassing the usual competitive bidding process on the grounds that VistA was obsolete and the VA and Pentagon systems had to be made by the same company in order to exchange information easily.

Ed Meagher, who served as VA’s deputy chief information officer and chief technology officer between 2001 and 2006, said that justification was baseless.

“There’s two canards here,” Meagher said. “One is that it’s important for DOD and VA to be on the same branded platform. That’s not true. There are much better ways to share data now. That’s a 20-year-old point of view.”

The biggest misconception, he added, is that VistA is broken and needs to be replaced.

“That couldn’t be further from the truth,” Meagher said, pointing to a recent VA pilot program that showed VistA can operate faster and at lower cost through cloud computing.

While there are downsides to VistA, which is built using a relatively old coding language and can be difficult to integrate with modern software, Baker said those issues have been overblown amid VA’s push to adopt the Cerner system.

“In order to sell this massive program, VA had to create a rationale,” Baker said. “VistA has its problems, but if you look at what has been sold to Congress, those problems have been trumped up.”

‘Just deal with it’

The main strength of VA’s homegrown health record system, Baker and Meagher both said, is that health care workers have customized it over the course of decades.

Unlike commercial systems, Meagher added, VistA is built to prioritize providing the best possible care rather than billing insurance companies.

“A lot of the reason that the Cerner record is failing out in Spokane is that, love it or hate it, the VistA system is the highest-rated electronic health record system as far as doctors are concerned,” Baker said. “And if you’re going to replace that system, you’ve got to figure out why do they want it.”

VistA also allows each VA facility to tailor the system to its unique needs, although the department has taken steps in recent years to rein in that customization. Baker said VA’s effort to transition to a single, standardized system has run into a fundamental tension between doctors and nurses who want control over how they care for veterans and leadership in D.C. that wants more central control.

Richard Kline, a Navy veteran and 30-year VA employee, worked his last day as an overnight administrator at Mann-Grandstaff on Oct. 23, 2020, the day before the Cerner system launched. While Kline, 61, had planned to work for two more years, he said the attitude of VA leaders toward concerns he and other employees raised about the Cerner system made him decide to leave early.

“From day one, it was just like ‘We’re going to do this. Don’t raise a stink about it. Just deal with it,’” said Kline, who still keeps in touch with his former colleagues. “I think it’s somewhat of a fearful place to work at right now. The stress level is high. People are just putting their heads down and just muddling through this thing.”

Jerry Anderson, a 62-year-old Navy veteran in Spokane, is “not one of these people who thinks change is a bad thing.”

“I’m one of those guys, when I retired from the Navy, I had to basically make a whole copy of my medical records and somehow see if they could translate that into my VA records,” he said. “Not easy.”

But Anderson, who worked in a human resources role at Mann-Grandstaff until 2018, called the Cerner rollout “a typical example of getting rid of one system before the new system is fully tested and vetted and ready to go.”

The main cause of the delay in transferring information to VA, Baker said, is that the Defense Department system still relies largely on paper records, which must be scanned and sent to the VA as PDF documents.

But Kushner’s decision won out, supported by three paying members of Trump’s Mar-a-Lago resort – a doctor, a lawyer and the chairman of Marvel Entertainment – who became de facto bosses at VA despite having no official roles in government, reporting by ProPublica revealed in 2018.

After VA Secretary David Shulkin left the department in March 2018, claiming Trump had ousted him for resisting efforts to privatize the Veterans Health Administration, Trump replaced him with Wilkie, who was then in charge of the Pentagon’s struggling Cerner rollout. Despite an internal report in April 2018 concluding the Cerner system was “neither operationally effective nor operationally suitable,” Wilkie signed a $10 billion contract with Cerner.

That same day, Trump nominated Wilkie, then the VA’s acting secretary, to officially head the department. The Senate confirmed him two months later with every Republican and all but nine Democrats voting in favor. Those voting “Yea” included Washington Sens. Patty Murray and Maria Cantwell.

While the VA moved forward with the Cerner rollout, problems with the system at Fairchild and other Defense Department facilities have persisted.

The Government Accountability Office, another federal watchdog agency, reported in September that 288 “system defects or adverse test findings” were still unresolved, including 61 “critical” incidents that “could result in mission failure” and 81 “major” incidents that “could cause partial failure.”

Despite dramatically speeding up the Cerner rollout at its facilities to meet a 2023 deadline, the report also found the Pentagon did not plan to do additional testing to find other problems.

Hayes, the VA spokesman, confirmed that VA chose to pilot the Cerner system in Washington because the Defense Department had done the same. VA revised its deployment schedule in August 2020, he said, because the pandemic “restricted VA and Cerner’s access to clinicians,” affecting their ability to deploy the new system in “larger and more complex medical centers, such as Puget Sound.”

‘Success is nonnegotiable’

Despite those warning signs and the Biden administration’s efforts to undo Trump-era initiatives in other federal agencies, Secretary Denis McDonough, Deputy Secretary Donald Remy and other VA leaders have maintained the department needs the Cerner system and “lessons learned” from Mann-Grandstaff will help other facilities avoid the same problems.

“I think we will get this effort back on track,” Remy told a House subcommittee in October, adding that the program would succeed “because success is nonnegotiable. It’s a must-do and we’re moving forward.”

While lawmakers have raised concerns about patient safety, staff burnout and the potential cost of the Cerner system, members of the House and Senate VA panels have maintained VistA has to be replaced and none have called for VA to scrap the Cerner program.

“We have a responsibility to our veterans to get the highest-quality care possible, and in this situation it includes a functioning health care record system,” Sen. Patty Murray, a Washington Democrat and member of the Senate VA Committee, said in an interview Tuesday.

After grilling McDonough over problems at Mann-Grandstaff in a July hearing, Sen. Jon Tester, a Montana Democrat who chairs the Senate VA Committee, told The Spokesman-Review, “I actually wish we were rolling out in Montana. I’d like to see this happen sooner, because I just think it’s going to serve the veterans a lot better.”

While the VA clinic in Libby is connected to Mann-Grandstaff, the rest of Montana’s VA facilities are part of a separate administrative region and are not included in the 2022 deployment schedule VA released Wednesday.

Some of the strongest criticism has come from Rep. Matt Rosendale of Montana, the top Republican on the House subcommittee charged with oversight of the Cerner rollout, who said in an April hearing, “The idea that the VA and DOD need the same company’s software to exchange medical records is, frankly, ridiculous.”

The Cerner records system has to be better, not just newer, Rosendale said.

“It’s unacceptable to be risking medical errors while bugs get worked out in a live environment,” he said in that same hearing.

On Wednesday, the VA announced a change to the program’s management structure that will eliminate the Office of Electronic Health Record Modernization in favor of a new “program executive director” position, to be filled by a DOD health official, supervising three new managers.

“I’ve never seen adding new layers of bureaucracy make a program more effective,” Baker said in response to the move.

Meagher said McDonough seems to think that “through heroic management and good speechifying we’re going to convince everybody to take an inferior product to be half as productive.”

Baker said he would like to see McDonough be more transparent about the root causes of the problems at Mann-Grandstaff but conceded the VA chief is likely facing pressure from the Pentagon to move the program forward regardless of the harm it does at VA.

“What VA is apparently doing is, ‘We can’t let this out, because then Congress is going to realize that we’re not doing very well and they’re going to cut our money, and so the last thing we want to do is admit any kind of a mistake,” Baker said.

Congress already has appropriated $6 billion for the Cerner rollout, and the House Appropriations Committee approved another $2.6 billion in June for the effort, despite members of the panel expressing doubts about VA’s ability to stick to the program’s 10-year timeline and $16 billion cost estimate. In reports earlier this year, the VA Office of Inspector General found the department had underestimated the cost of the project by as much as $5.1 billion, raising the likely total cost to at least $21 billion, though not all of that money would go to Cerner.

“We’ve had a long string of leaders at the VA tell us that the intention is to finish in 10 years, the intention is to be transparent, the intention is to not affect patient safety, and none of that ever happens,” Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz, a Florida Democrat who chairs the House subcommittee that controls VA’s funding, said in an October hearing, months after her panel had approved the extra money.

Congress passed a short-term spending bill Thursday to extend government spending at its current levels until Feb. 18. Since VA already got $2.6 billion for the program last year, the Cerner project is on track to receive virtually the same level of funding unless lawmakers change their minds.

Murray, who also sits on the Senate Appropriations Committee, said Tuesday she is not inclined to withhold funding from VA, because “then you don’t allow them to continue to do the work which is necessary, which is to make sure we have really good health care record systems at our VA.”

Baker said the best-case scenario, which he gives a 10% chance of happening, is that VA succeeds in replacing VistA with the Cerner system at a cost of at least $30 billion over 15 to 20 years. The more likely outcome, he said, is that VA brings the Cerner system to more facilities during the Biden administration – risking harm to more veterans – before a future VA secretary scraps the program.

“The biggest problem I believe they have is they think moving forward starts with staying on the same path,” Baker said, “and we’ve already proven this path doesn’t work.”

According to an updated schedule the VA released Wednesday, which it said is still subject to change, it will deploy the Cerner system in Columbus, Ohio, on March 5, followed on March 26 by the Walla Walla VA Medical Center, including its clinics in Lewiston, Richland, Yakima and three more in northeastern Oregon. The next rollouts are slated for Roseburg and White City, Oregon, on June 11, Boise on June 25 and Anchorage, Alaska, on July 16.

VA’s Puget Sound facilities, including its Seattle and American Lake hospitals and eight other facilities that serve about 120,000 veterans, are scheduled to make the switch Aug. 27. The final planned launches of 2022 are in Battle Creek, Saginaw and Ann Arbor, Michigan, on Oct. 8 and in Portland on Nov. 5.

In a hearing Wednesday, Murray told McDonough she didn’t want to see the Cerner system deployed at other sites in Washington “until it’s fixed and it’s ready to go.”

Rep. Mike Bost of Illinois, the top Republican on the House VA Committee, responded to the new schedule by urging McDonough and Remy to “reconsider” the plan to bring the Cerner system to other facilities in just a few months.

“The VA electronic health record modernization effort has become a series of broken promises,” Bost said in a statement. “The serious issues with the new system in Spokane are undeniable. Yet, VA has been unwilling to face the music and make the fundamental changes that are necessary to fix them.”

But Mike Tonkyn, a Marine veteran in Spokane who has seen the Cerner system’s problems firsthand, said lawmakers themselves bear responsibility for the problems.

“Every time I see a problem with the VA, I look at Congress,” Tonkyn said. “They like to blame any bureaucracy for any problem that they have, and there can be a problem in a bureaucracy, but the bureaucracies are owned by the elected officials.”

S-R reporter Arielle Dreher contributed to this report.