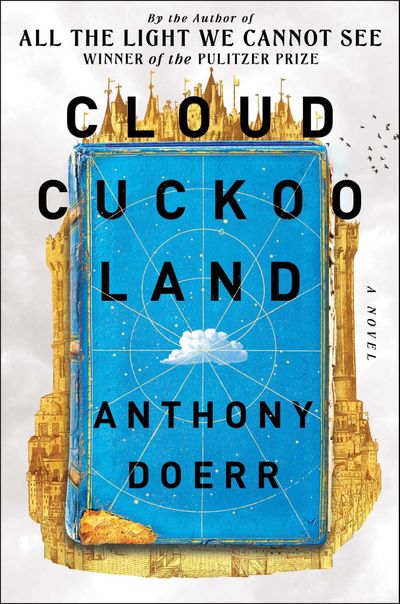

Review: Anthony Doerr’s ‘Cloud Cuckoo Land’ requires work, but the payoff is worth it

With a melding of historical fiction, social commentary, fairy tale and science fiction, Anthony Doerr delivers a deft and intricately woven tale that makes “Cloud Cuckoo Land” one of the most memorable books of the year.

The novel challenges the reader with five characters spanning five centuries in the past and one into the future amid an unspoken promise that all will wind up together in the end. Doerr delivers on that promise amid colorful details and a rhythmic writing style that keeps the story moving toward the reader’s final reward.

But it’s a payoff that requires work. I found myself starting and stopping the novel several times. Still, all that’s really required is to form an early attachment to at least one of the characters. It’s like the multiple jigsaw puzzles that one character struggles with in the novel, ending up with pieces strewn across the floor and under furniture.

Yet Doerr, Pulitzer Prize winner for “All the Light We Cannot See,” doesn’t let the reader wander too far without offering a spark in each chapter that suggests somehow this will all make sense.

The thread winding together the fabric of the tale is the fictional story of the title, a mythical book from real-life lost author and philosopher Antonius Diogenes. “Cloud Cuckoo Land” is told in a series of manuscripts that has survived through the centuries by the sheer will of those to whom the story has touched – and which over the centuries ends up being the saving grace for all five characters.

The book opens with Zeno Ninis, an 86-year-old ancient literary enthusiast who has written a play he’s producing with local schoolchildren in the present-day Lakeport, Idaho, library. Outside, however, sits Seymour Stuhlman, packing a gun in his jacket and a bomb in his backpack, disenchanted with the real estate development that threatens the woods and the rural surroundings, his only sanctuary from the noisy world around him.

As an explosive drama unfolds at the library, Doerr transports us to an equally violent world of 1453 as Constantinople prepares to fall to the Ottoman Empire.

Inside the fabled walls of the city works Anna, a 13-year-old seamstress in a sweatshop that weaves intricate robes for priests. Anna, however, learns to read and develops a knack for stealing manuscripts and selling them to Italian scribes trying to save pieces of literature from the trash bin of history.

This is where she discovers the Diogenes book about a shepherd named Aethon, who falls under magical spells and takes the shape of a donkey and a bird in order to find a mythical paradise. It’s a kind of “The Wizard of Oz”-type of tale Anna reads to comfort her dying sister.

Yet as if all that is not complicated enough, outside the walls is Omeir, a farm boy wrangled into the service of the Ottomans.

But wait. Doerr then hurls us into the 22nd century, where another teenage girl, Konstance, lives in the 64th year of a generations-long space voyage. She remains aboard a spaceship hurtling toward another galaxy to a new planet for humanity to colonize, away from a dying Earth they apparently have destroyed.

Bullying, environmental sustainability and the tendency of humans to beat down the weakest links and consume everything around them are the prevailing themes of “Cloud Cuckoo Land.”

Technological achievements, from the Ottoman cannons that can blast through the walls of Constantinople to the artificial intelligence that drives the spaceship Argus, are of questionable value.

The real heroes, however, are not the main characters but rather librarians.

Libraries, and those who run them, contain the answers all the characters seek. The librarians help the struggling souls looking for meaning, and they find their way through the classic stories of Ulysses, Greek tragedies and the myth where redemption always seems possible.

With “Cloud Cuckoo Land,” Doerr reminds us even in a complex and unforgiving world, happy endings are still possible.

But first, we must work toward them.

Ron Sylvester has been a journalist for more than 40 years with publications including the Orange County Register, Las Vegas Sun, Wichita Eagle and USA Today. He currently lives in rural Kansas.