We the People: The president has lofty power when it comes to foreign conflicts, except in one area

Each week, The Spokesman-Review examines one question from the Naturalization Test immigrants must pass to become United States citizens.

Today’s question: Who is the commander in chief of the U.S. military?

President Joe Biden made the final decision to withdraw troops from Afghanistan, a power he was granted by the Constitution. Just like President Donald Trump had the power to start the process of ending the war, President Barrack Obama had the power to spark a surge of troops there and President George W. Bush had the power to send troops to Afghanistan in the first place.

The President of the United States holds the responsibility of leading the military from Article 2, Section 2, Clause 1: “The President shall be commander in chief of the Army and Navy of the United States.”

The drafters of the Constitution felt that one person needed to be the leader of the military to allow for swifter action, according to a Cornell Law School briefing on the topic. They also believed that person should be a political leader.

The president can single-handedly direct and launch operations, launch nuclear weapons, and order the deployment of military troops. However, there is one catch: the Declare War Clause. This clause gives Congress the power to declare war, not the president.

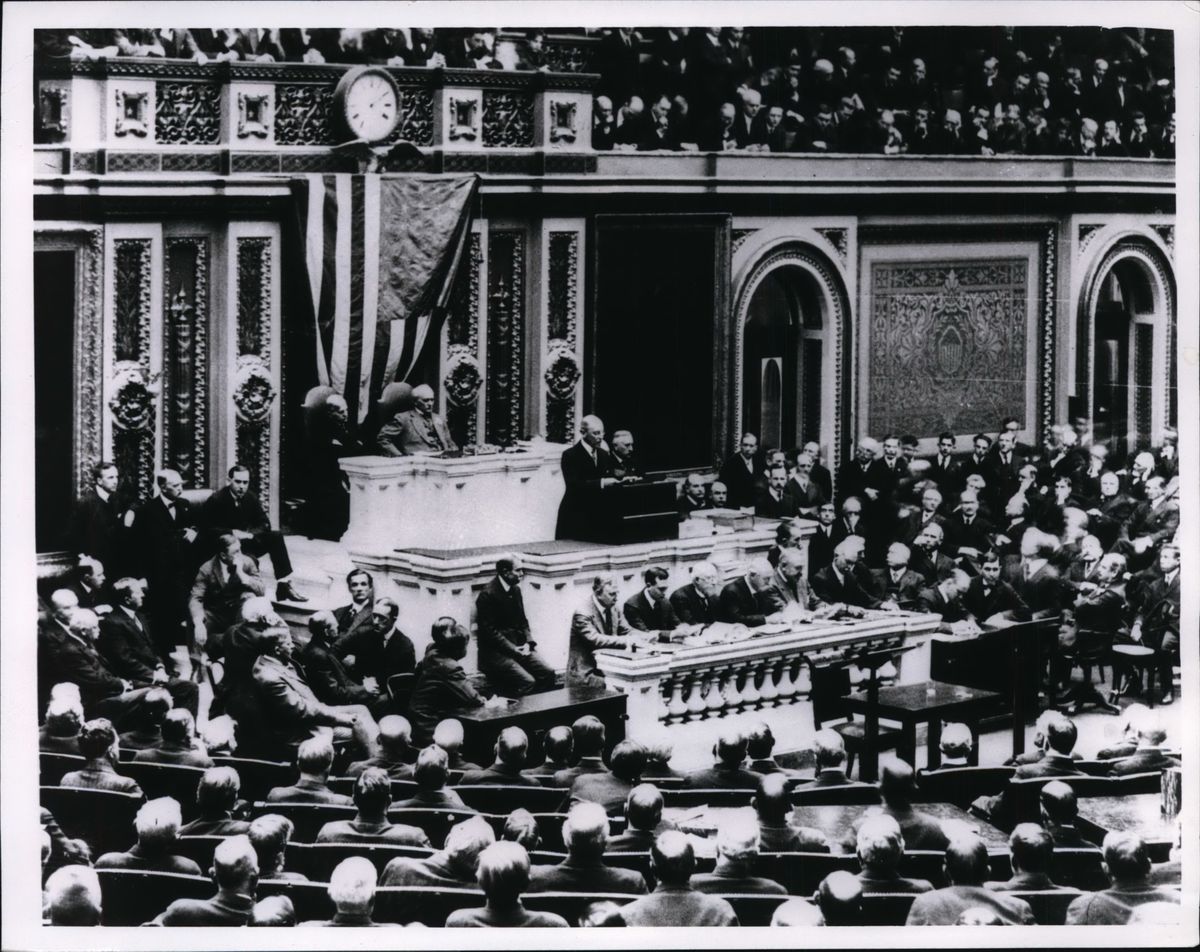

You might have heard on the news that the United States was “at war” in Afghanistan. And although this is true within the modern definition of war, Congress hasn’t technically declared war since World War II in 1942 against Bulgaria, Hungary and Romania (the U.S. declared war in 1941 against Germany, Japan and Italy).

So, if Congress has the sole power to declare war, how is it that the United States has engaged in military action in Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan and multiple other countries without declaring war? The answer is that a president’s power as commander in chief gives the president wide authority to essentially put the nation at war.

“As commander-in-chief of the military, the president can simply order the military without a declaration of war, and virtually every president has taken advantage of this ability,” an article from the National Paralegal College explains.

The amount of authority that the Constitution grants the president has been subject to debate for decades. Mary Pat Treuthart, a Gonzaga University law professor, attempted to explain different viewpoints in regards to the Commander in Chief Clause.

“Some constitutional law scholars believe that the President is granted broad power under the CCC. But even those who subscribe to this expansive view acknowledge that the extent of this power is not well-defined. Scholars who interpret the CCC more narrowly will typically refer to the fact that it is Congress that has the constitutional power to declare war and to support the Army and Navy.”

She said that recent events such as Biden’s troop withdrawals from Afghanistan and Trump’s “possible use of the military to quell domestic disturbances in U.S. cities” prompted debate about the use of this presidential authority in different contexts.

Near the end of the Vietnam War, Congress approved over the veto of President Richard Nixon the War Powers Resolution, which sets restrictions on a president engaging in military conflict. A president must give Congress notice of military action and seek congressional approval within 60 days of a military campaign. Even this, some legal experts have said, has sometimes been ignored by presidents.