This column reflects the opinion of the writer. Learn about the differences between a news story and an opinion column.

Getting There: Can Spokane’s light rail effort be revived?

Phyllis Holmes, left, Molly Jakubczak, K.C. Traver and Dick Raymond, members of the Inland Empire Rail Transit Association, break out in laughter Friday as Jakubczak says, “When we started this project, none of us had gray hair.” (DAN PELLE/THE SPOKESMAN-REVIEW)Buy a print of this photo

When Dick Raymond walked into the first meeting about the possibility of light rail in Spokane, he was, like many, more than a little skeptical.

“I literally asked, ‘Why are we doing this?’ ” he said on Friday. “Because I thought it was a –”

Raymond was searching for a word, and his fellow members of the Inland Empire Rail Transit Association were happy to help him out.

“Boondoggle,” they agreed.

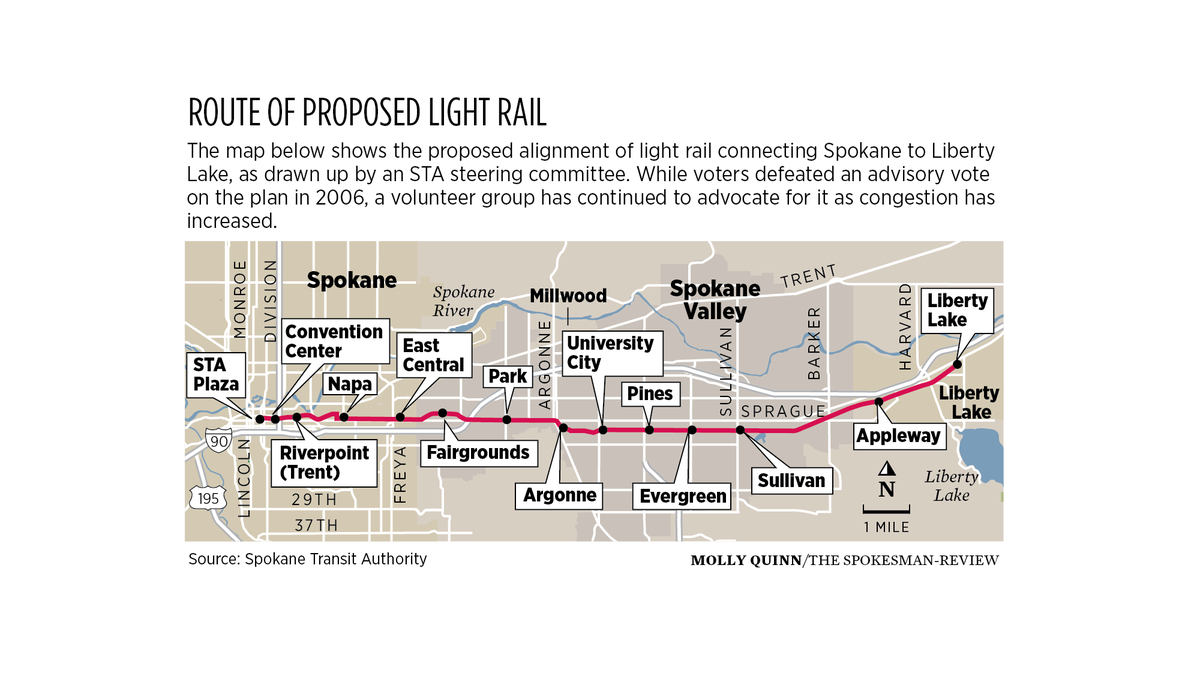

But that was more than two decades ago, in 2000, soon after the Spokane Transit Authority and the Spokane Regional Transportation Council created a light rail steering committee. That panel began considering the design and feasibility of a form of transit that was already well established in Portland and taking shape in Seattle.

At the time, Raymond was the city of Spokane’s principal engineer for capital projects. So he knew a thing or two about large-scale infrastructure work. Or thought he did.

As he gathered more information, Raymond said, his attitude flipped 180 degrees.

“My thoughts morphed over the months to ‘this makes a lot of sense,’ ” said Raymond, who became one of the proposal’s biggest boosters.

What made sense, he said, was not so much the relationship between light rail’s upfront costs and its projected ridership right out of the gate, which the implementation plan predicted would number just 3,500 daily boardings by 2025. Rather, Raymond said, it was the long-range potential to reduce congestion, boost economic development and guide the future of the region’s growth.

Advocates of light rail did their best to make more believers like Raymond.

“We did literally hundreds of presentations,” said Molly Jakubczak, a former STA communications manager and longtime member of the Inland Empire Rail Transit Association.

She also took officials, politicians and regular citizens to Portland to take light rail for a ride and to learn about its benefits.

In an effort to sway those concerned about cost, members of the steering committee also downgraded their vision over time.

They began with the “biggest, the brightest and the most expensive” vision, one that conceived of high-frequency electric trains coming and going on elevated tracks from the airport to Liberty Lake.

But over time the effort to reduce cost led to a preliminary design that included a single track, a shorter route, less frequency and a plan to use biofuels instead of electricity for power.

The fact that light rail’s potential in Spokane was so extensively studied and planned, with the aid of some $9 million in grant funding, at the turn of the 21st century has largely been lost to the mists of time.

And many of those who do remember the effort recall not the fact that it got far enough for an implementation plan to be drawn up, but rather that it was the subject of a pair of unsuccessful advisory votes in 2006.

“You’re up against, ‘Wasn’t there a vote on that? And didn’t you lose?’ ” said K.C. Traver, a member of the Inland Empire Rail Transit Association who helped analyze the possibility of light rail for the Spokane Transit Authority’s now-defunct light rail steering committee.

But he, like his fellow association members, argues that vote was a flawed mechanism for deciding whether to move forward with the project.

Phyllis Holmes, who served on Spokane City Council for eight years and on the boards of STA and SRTC, said the advisory vote was “very deceptive.” Despite that, she says the votes were close.

A vote on whether to pursue funding failed 54% to 46%, and a vote on whether to use STA funds for engineering, design and environmental analysis lost 52% to 48%.

While advocates rallied to form the Inland Empire Rail Transit Association and their campaign persisted despite the defeat, their momentum was largely lost.

In the years since, STA has shifted its focus from light rail to bus rapid transit and other high frequency forms of bus service.

That transition has led to the City Line, which is under construction and expected to open early next year, and to planning for a second line along Division Street.

While the rail association’s members support those projects, they argue bus rapid transit lacks some of light rail’s advantages, especially its power to help corral the forces of growth and development.

“Buses follow development,” Holmes said, “but development follows rail.”

There’s also the simple allure of rail, Traver said.

“More people will get on a train because it’s a more pleasurable, predictable way of getting around,” he said.

While it’s impossible to deny rail’s appeal, STA is building permanent stations for the City Line, using a “proof-of-payment” system and promoting transit-oriented development along its route, all features that appear likely to at least close the gap with what light rail may have offered.

And there’s also the advantage of cost.

Construction of the City Line will cost an estimated $92.2 million, while the recommended light rail alternative was estimated to cost $263 million in 2006 dollars.

Those costs would undoubtedly be far higher now, which only exacerbates the scale of the missed opportunity in the eyes of light rail’s advocates. Had everything gone according to plan, construction could have started as early as 2008 and light rail could have begun operating in 2012.

“I think 20 years from now, we’re going to think, ‘We could’ve paid for that for chump change,’ ” Traver said.

There’s also the comparative cost of increased traffic to consider.

With Idaho moving forward on a project to widen a 15-mile stretch of the interstate at an estimated cost of $425 million, the price of light rail looks more reasonable. And with smoke darkening the summer sky, the payoff in the form of reduced emissions is more appealing too.

“We predicted what’s happening today,” Holmes said. “We saw it coming.”

And she said light rail still offers a way out of a future with ever larger and crowded highways.

“We don’t have to keep adding to the freeway, because it doesn’t do anything,” Holmes said.

While light rail remains a possibility in STA’s long-range plan, Karl Otterstrom, the agency’s director of planning and development, said the pattern of where and how the federal government is investing in transit makes it unlikely such a project will come to the I-90 corridor in the next 10 to 15 years.

But that doesn’t mean money won’t come to boost public transit along the freeway, he said.

The STA Moving Forward plan, which levied a small sales tax to fund a slate of projects for the agency to implement over a 10-year time frame, included a two-year pilot project that would aim to establish frequent high-performance transit along I-90 between Spokane, Post Falls and Coeur d’Alene by 2025.

The plan also features a slate of other projects designed to boost service and amenities between Spokane and the Idaho state line, including express routes to and from Liberty Lake, a new transit center at Mirabeau Point in Spokane Valley and an expanded Liberty Lake park-and-ride.

All of that said, Otterstrom said light rail could figure in the region’s long-term transit picture.

“Rail is a very effective way to carry lots of people and to create exclusive rights of way, so I would never exclude the possibility of rail in the future of a regional strategy,” he said.

As for making it more than a possibility, the members of the Inland Empire Rail Transit Association are ready to pass the torch.

“When we all started this project, none of us had gray hair,” Jakubczak said. “It’s time for the next generation to step up.”

If and when they do, Holmes said, they will have a foundation to stand on, in the form of a trove of documents stored on the light rail association’s website, inlandrail.org.

And while Spokane missed its chance at a head start, the challenges light rail advocates hoped to combat, including gridlock and sprawl, aren’t going anywhere, Jakubczak said.

“The rationale for why the project started in the first place is still relevant today, if not more so,” she said.

Passenger rail meetings

Speaking of rail, the passenger rail advocacy group All Aboard Washington will be hosting meetings in Spokane and Cheney on Thursday and Friday to discuss its vision for improved train service, including new daytime service, new connections to Central and Western Washington via Yakima and Auburn, and connections to Spokane Airport.

The Thursday meeting will begin at 5 p.m. at the Spokane Airport Event Center, 9211 W. McFarlane Road. To register, visit aawa.us/events/2021-train-trek-spokane-area.

The next day, the group will convent at 10 a.m. at the Wren Pierson Community Center, 615 4th St. in Cheney. Register for that meeting at aawa.us/events/2021-train-trek-cheney.

Offer input on Valley streets program

Spokane Valley is seeking input about its pavement management program, which includes both preservation work and maintenance work including snow plowing, pothole patching and sidewalk repair. To learn more and take a survey, visit spokanevalley.org/pmp.

Work to watch for

An arterial chip-seal project will lead to the following issues:

- Post Street between Cleveland and Maxwell Avenue will have lane closures with flaggers Monday.

- Wellesley Avenue between Milton and Ash Street will have lane closures with flaggers on Wednesday.

- Crews will be working at Freya Street between 37th Avenue and Palouse Highway on Thursday.

Traffic-calming and pedestrian-safety work will be underway at the following locations: Nevada Street, from Crown to Sanson Avenue; Cook Street, from Sinto to Nora Avenue; Milton Street, from 16th to 14th Avenue; the intersection of Second Avenue and Oak Street; the intersection of Cedar Street and 14th Avenue; the intersection of 26th Avenue and Bernard Street; Assembly Street, from Sanson to Bismark Avenue; Columbia Avenue, from Alberta to Cochran Street; the intersection of Gordon Avenue and Post Street; and the intersection of Post Street and Waverly Place.