Undefeated since 1941: Gonzaga’s football program had its share of success before it was disbanded

You’ve seen the shirts. Maybe you even have one.

“Gonzaga Football,” they read, “Undefeated Since 1941.”

Cheeky, ironic – a welcome touch of self-deprecation at a school not given to it much anymore. The gag being, of course, that Gonzaga University hasn’t fielded a football team since 1941.

It’s also not exclusive apparel. Campus bookstores at Marquette, Long Beach State and Mount St. Mary’s, among others, have sold the same shirt with the logo and year amended appropriately. Gonzaga’s main distinction is that it got out of the football business even earlier than most of the private colleges and universities that were the first to find the going too expensive in the 1940s and ’50s.

Nowadays, of course, the Bulldogs can push the envelope of going unbeaten in a sport they actually play.

But in that respect, the mothballed football program still has bragging rights. Because it did once make it through a full season undefeated, with a team that came to be regarded as the best Gonzaga produced.

It was led by a Hall of Fame coach who helped change the way the sport was played and featured a cast of characters as outsized in the campus consciousness then as the Drew Timmes of today – playing at a grand-for-its-time stadium that served as a Spokane social hub not unlike the basketball arena that now stands a few yards away.

And it all happened a mere 97 years ago.

•••

Football at Gonzaga was never the juggernaut – even on a regional scale – that some of its long-ago alums liked to imagine. While the Bulldogs, as they came to be called, held their own against rivals Idaho and Montana – and fellow Catholic institutions down the coast – they won just six of 44 games over the years against the Northwest foursome now in the Pac-12.

But it was more than a footnote, too.

Twenty Gonzaga players would go on to see action in the National Football League’s first two decades, and two made it to the Pro Football Hall of Fame. The Bulldogs would meet West Virginia in a Christmas Day bowl game in San Diego in 1922, and travel far – to Texas Tech, Detroit, Arizona State and powerful Haskell Institute – chasing their football ambitions.

Indeed, the first football seed in the Inland Northwest was planted on the GU campus, on Thanksgiving Day 1892.

The Spokane Amateur Athletic Club, stocked with some recent graduates of Eastern colleges, formed a team and began practicing for a game, with no specific opponent in sight. A mere suggestion on the sports page of The Spokesman-Review was enough to spur Gonzaga’s tiny student body into being the guinea pigs, with Dr. Henry Luhn – who had captained Notre Dame’s first team in 1887 before coming west to start a medical practice – drafted as coach. He put the students through their first paces on Tuesday, suited up as fullback with them on Thursday and led Gonzaga’s team – outfitted in white painters’ coveralls – to a 4-4 tie.

“The game was noteworthy,” read one newspaper account, “because of the absence of slugging, consequently there were no (disqualifications).”

But momentum was fitful. The sport was discontinued – first intercollegiately, then even as an intramural activity – out of safety concerns near the turn of the century. The advent of the forward pass mitigated those somewhat, and so Gonzaga resumed play in 1907 and hired its first full-time coach, R.E. Harmon, in 1913, though that, too, was short-lived as the school struggled financially.

But finances didn’t seem to be a care in 1920 when graduate manager Eugene Russell – the equivalent of today’s athletic director – hired Charles E. “Gus” Dorais to coach all the school’s athletic teams.

Gonzaga’s stab at big-time football had begun in earnest.

•••

Gus Dorais wasn’t Russell’s first choice. He’d tried to shoot for the moon and offer the job to none other than Jim Thorpe, Olympic decathlon gold medalist and American legend, who at the time was playing for the Canton Bulldogs and doubling as president of the league that would become the NFL.

But if Dorais was No. 2, he had his own cachet, and better coaching credentials. He had been Knute Rockne’s teammate at Notre Dame, the quarterback pitching spirals – as much as those old, fat footballs spiraled – to his roommate and turning the forward pass into the Fighting Irish’s principal offensive weapon.

If he wasn’t the “father of the forward pass,” as was often written – and which he generally dismissed – he at least midwifed the overhand motion, the ball cocked behind his ear.

He’d also already coached for four years at Dubuque College in Iowa before becoming director of sports at Camp McArthur during World War I. Then came a short stint as Rockne’s assistant that led to him accepting a one-year contract from Gonzaga for $3,500, back when the school didn’t guard such details like nuclear launch codes.

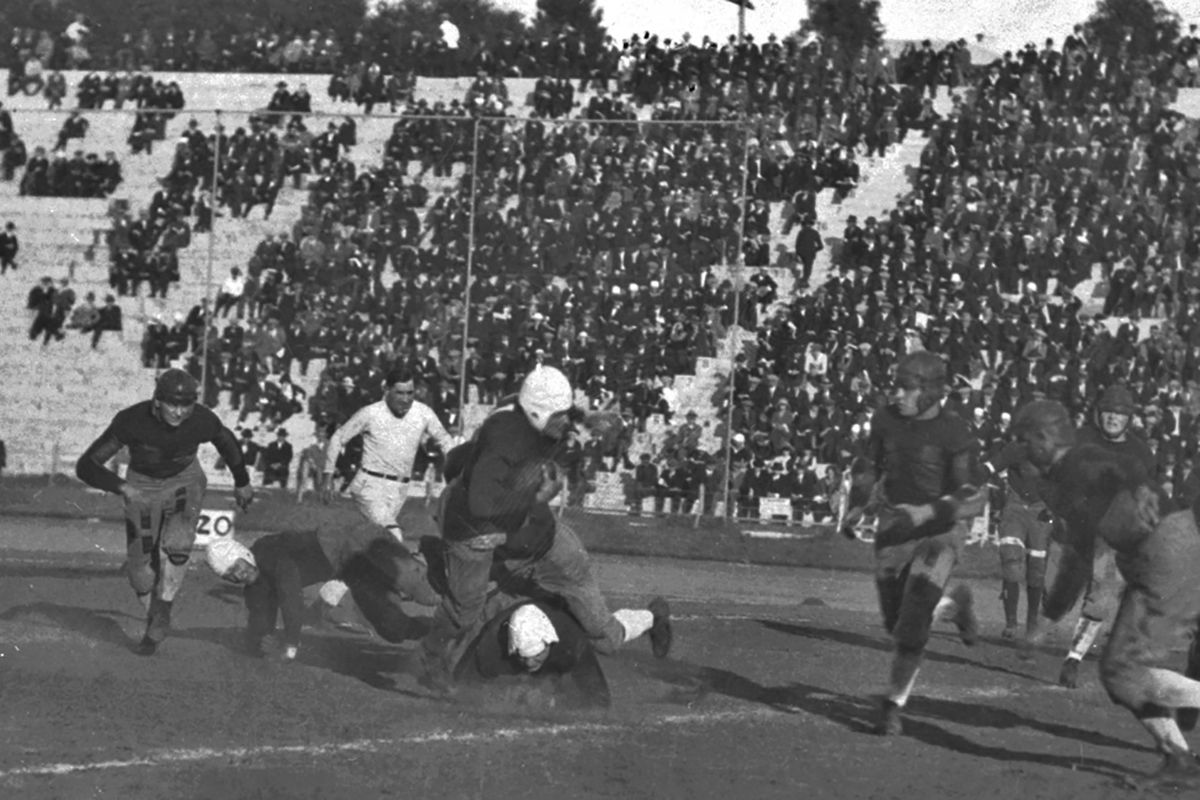

His first two GU teams had indifferent success. But in 1922 the school opened its new 5,000-seat, $100,000 stadium – expansion would eventually take it to 11,000 seats – in a 10-7 loss to Washington State. Four straight victories would follow, including a 77-0 whitewash of Wyoming. A 21-13 loss to West Virginia on Christmas brought the season to a 5-3 finish, but enthusiasm was such back in Spokane that five civic clubs banded together to raise $10,000 and pay off the stadium debt.

The next year, the Bulldogs beat WSU for the first time, 27-14, and by 1924 there was another bonus. After several earlier denials, membership in the Pacific Northwest Intercollegiate Conference was extended, allowing GU to join WSU, Idaho, Montana, the Oregon schools and three other Northwest privates in competing for a championship.

Gonzaga warmed up for conference play with a 27-0 blitz of Cheney Normal – better known today as Eastern Washington – that included a blocked punt for a touchdown by center Arthur Dussault and a 25-yard scoring pass from Houston Stockton to Ray Flaherty.

Now, about those fellows …

•••

One of today’s favorite media time-wasters – and gobbled up by sports consumers – is the Mount Rushmore treatment. Take a pro franchise or a college program and pick four figures whose faces would be chiseled out of an imaginary mountainside as a monument to their roles and legacies. Argue. Repeat.

At Gonzaga, this is a nearly impossible endeavor given that its sporting stature has exploded nationally in the past two decades and is tilted so heavily to basketball – in essence, turning the first 100 years of athletics into an afterthought.

Make it a pre-World War II Mount Rushmore, however, and there would be little argument. Certainly a case could be made for Tony Canadeo, the Green Bay great and future Pro Football Hall of Fame inductee, but he left Gonzaga in 1941 as football was lurching to its end.

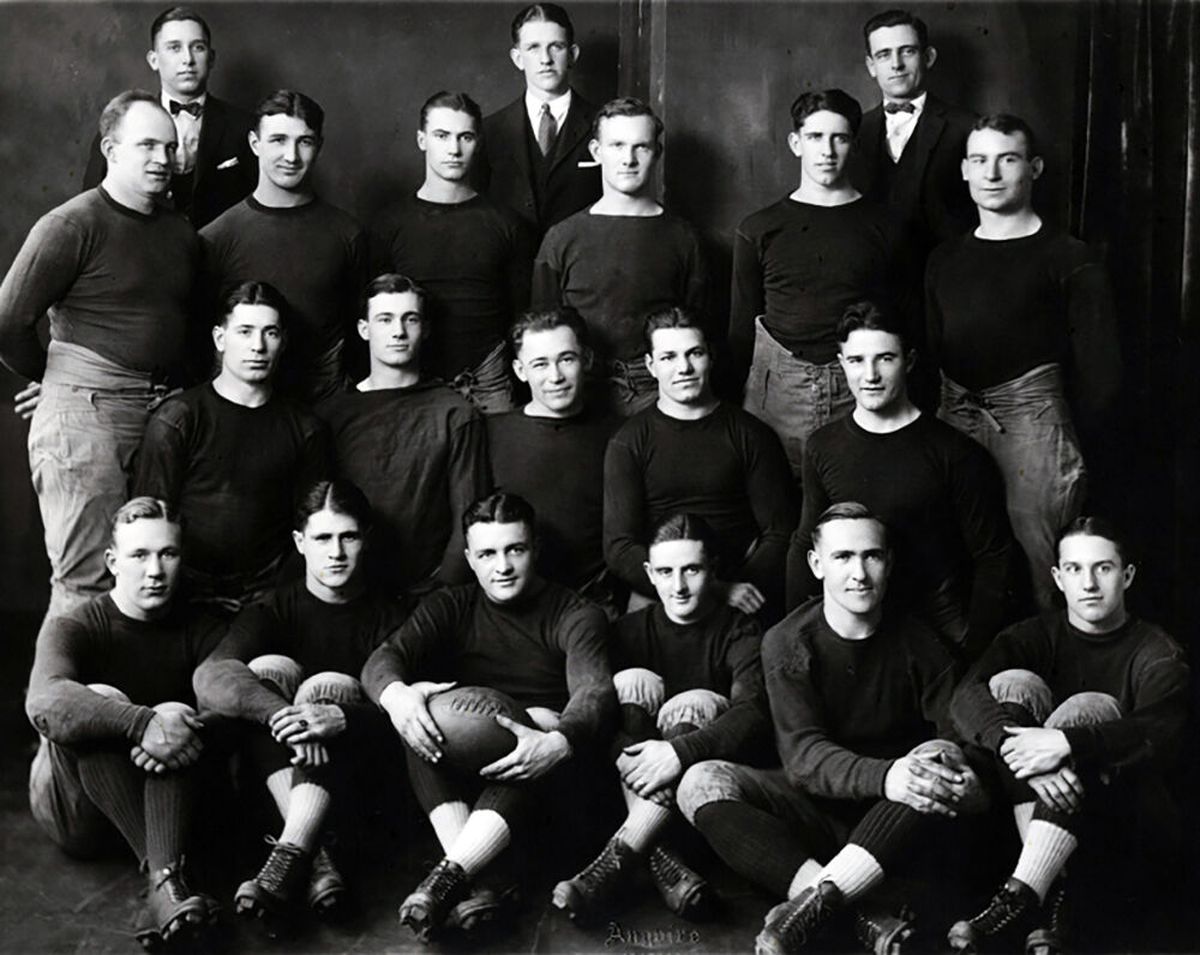

But Gonzaga’s early athletic identity – and some of its enduring identity, as well – was embodied in Dorais, Dussault, Flaherty and Stockton.

Dorais’ Notre Dame pedigree alone gave Gonzaga national credibility. After his first year in Spokane, he rebuffed numerous suitors – Idaho, Marquette, Wisconsin and, for a time, Detroit. But he also endeared himself with his manner.

“He had so much consideration for his players,” Flaherty said when Dorais died in 1954, “that they always gave their best for him.”

Flaherty absorbed those lessons. Raised in Spokane, he was a steady end with speed, and during an eight-year NFL playing career he led the league in all three receiving categories in 1932. But his greatest influence was as a coach, steering Washington to NFL championships in 1937 and 1942 with Sammy Baugh as his quarterback. A number of Gonzaga’s NFL alums – Max Krause, Ed Justice, Ray and Cece Hare – found their way to his Washington rosters and earned rings.

Stockton, too, won an NFL title, in 1926 with the Frankford Yellow Jackets. But his reputation will forever be tied to Gonzaga – as John Stockton’s grandfather, yes, but also as possibly the best football player in the school’s history. A native of Parma, Idaho, he transferred to GU from Saint Mary’s – and left an indelible impression.

“Houston Stockton, as a forward passer, is the best man in the world,” insisted former Idaho – and later Gonzaga – coach Robert Mathews, once Dorais’ Notre Dame teammate. Extolling Stockton’s gifts as a passer, runner and punter to The Spokesman-Review, he concluded, “He comes nearer being a whole team himself than any player I have ever seen.”

And Dussault? Well, he never had a pro career – he passed on a $125 a game salary to coach at Gonzaga High School, which he’d attended after coming from Butte. By 1940, he’d become an ordained Jesuit and remained a fixture on campus until his death in 1991, tending to almost every aspect of Gonzaga life at one time or another – fundraising, recruitment, campus planning. The lake on the campus’ southern border bears his name.

“No one reflected the spirit and character of the place as much as he did,” said the school’s late president, Rev. Bernard Coughlin.

•••

Other notable figures were on that 1924 team. Matt Bross and Hec Cyre both played in the NFL. John “Puggy” Hunton returned as the school’s last football coach in 1939. Mel Ingram earned 15 letters and remains possibly Gonzaga’s best all-around athlete of all time. And before 240-pound Ivan “Tiny” Cahoon went off to play for the Green Bay Packers, he was a forbidding Pontius Pilate in the Gonzaga Dramatic Society’s production of “Golgotha.”

The signature moments of Gonzaga’s best season came during the first two Saturdays of October. The Bulldogs salvaged a 0-0 tie with Idaho in Spokane with a defensive stand on their own 5-yard line. A week later in Pullman, two touchdown passes by Stockton to Flaherty and Spokane’s Don Jones staked Gonzaga to a lead that more defensive grit made stand up for a 14-12 victory.

On a muddy field at Montana, the Grizzlies were spotted two long touchdowns and Dorais was moved to rare moment of sarcasm at halftime – “What a fine bunch of football players!” he snorted.

But Stockton – running for 310 yards – brought the Bulldogs back for a 20-14 victory.

There were also wins over the Multnomah Athletic Club of Portland – which had tried to lure Dorais to play for it fresh out of Notre Dame – and Whitman, and another 0-0 tie in a rematch with WSU in Spokane on Thanksgiving that packed in 8,000 fans and grossed $9,807 in gate receipts, nearly double what the Cougars and Washington made that year in Seattle.

That made the 5-0-2 Bulldogs conference co-champions with Idaho. Today, the “Simple Rating System” used by College Football Reference, ranks them 29th for that 1924 season. Idaho was No. 8 and Stanford – 3-0 winners over Idaho – ninth after losing the Rose Bowl to Rockne’s undisputed national champions, Dorais watching from the sidelines.

But the coach finally succumbed to Detroit’s rather relentless entreaties and announced his departure the following spring, to be succeeded by another Notre Dame alum, Maurice “Clipper” Smith. But even as the winning continued, Gonzaga could never seem to achieve – or afford – the football heights its ardent backers imagined.

World War II gave the school’s fathers reason to shutter the program “for the duration of the war” after the 1941 season. Finances – a UPI story said the program had lost $350,000 the previous decade – gave them reason not to bring it back. The stadium’s razing in 1949 made it final.

And birthed a clothing line: Undefeated Since 1941. Plus that one special year in 1924.