‘Decades ahead’: Berg’s niece explores the city’s history as a heart attack trailblazer in new book on the ‘Spokane Experience’

A radical idea 50 years ago to do bypass surgery on a person in the midst of a heart attack happened in Spokane for a reason.

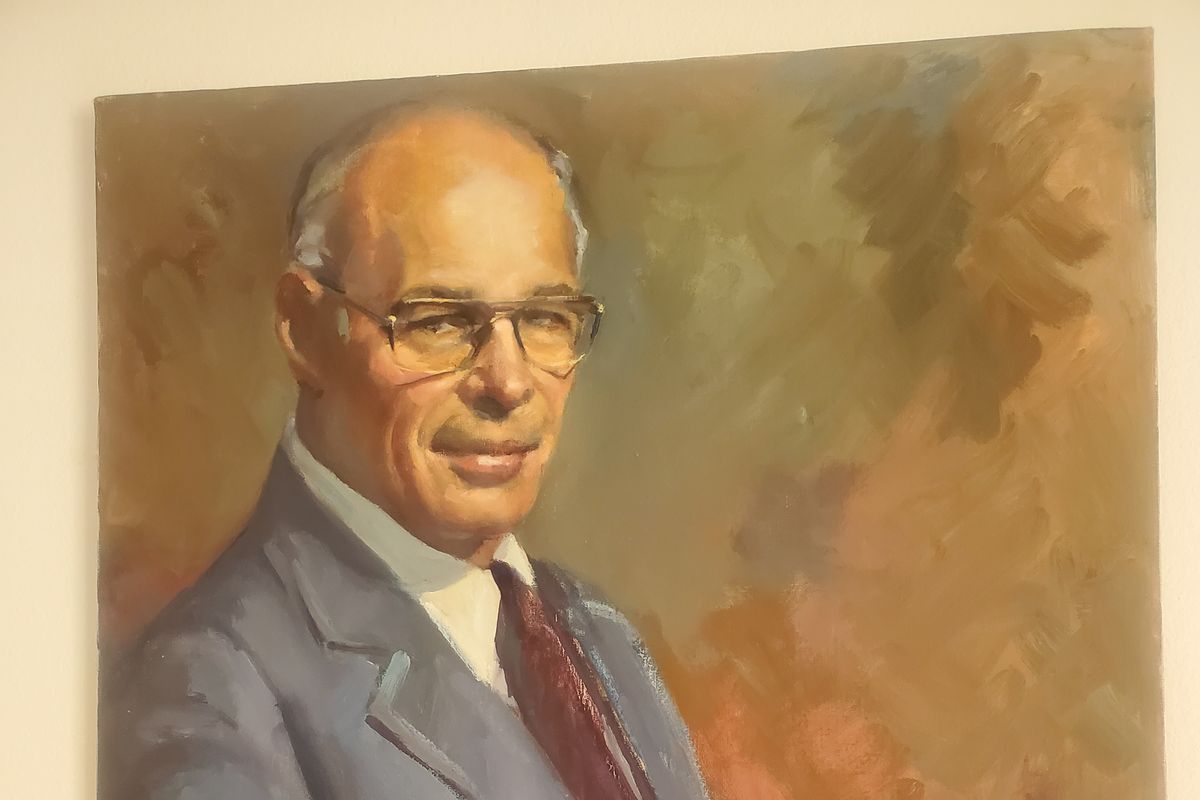

The milestone has its roots in 1952, when Dr. Ralph Berg and a team began researching new ways to treat heart problems. They developed groundbreaking cardiac care approaches, which by the 1970s drew criticism for the private doctors’ aggressive treatment of heart attacks against the then-standard drug intervention and bed rest.

In 1971, the coronary revascularization – or bypass surgery – became a foundation of the “Spokane Experience.” The 1970s were a decade when Spokane heart doctors continued the emergency surgeries despite peer rejection. It took a landmark 1980 New England Journal of Medicine paper, with their body of work collected, to usher in what became common practices for heart attacks, said Spokane resident Dr. Tracy Berg, a general surgeon and niece of the late trailblazing heart surgeon.

“It was a snapshot in time, a 10-year period when Spokane was basically decades ahead of everybody else in terms of what a heart attack was, how to treat a heart attack and doing it with a very difficult procedure,” she said. “After 1980, it was spread more widely.”

“The 1980 paper sort of embodies the term, the Spokane Experience, the definitive paper about how to treat a heart attack, what is a heart attack, and in Spokane between 1970 and 1980, they did that work using open-heart surgical procedure in an emergency situation at a level of surgical skill that I can guarantee you does not exist anywhere else on earth today.”

That first bypass followed a theory presented to Berg and his colleagues, she said. Cardiologist Dr. Francis Everhart, attracted here by Spokane’s cardiac work, theorized that a clot in the vessels might be causing harm, rather than a clot occurring after an attack. If so, a clot had to be removed or bypassed quickly to prevent heart muscle damage.

At the time, the prevailing thought was that anything done to the heart during an attack – even a catheterization – would increase the risk of serious rhythm issues.

However, Ralph Berg agreed with Everhart, which meant either he or Berg’s partner, Dr. Robert Kendall, would operate under the right conditions.

Tracy Berg said her uncle agreed because he understood the significance of heart muscle damage from what he knew about “blue babies,” a term for newborns with congenital heart defects. Her uncle worked on congenital heart defects in children, but what many people don’t know is he had a blue baby of his own, Jason Berg, born in 1969 with a complex transposition of the great vessels.

Around that motivation, Tracy Berg has written a book, “Blue Baby and The Spokane Experience.” It is targeted for an August release.

“It’s just such an amazing story, knowing my cousin and uncle, and finally getting the story from my uncle as to why he would agree to such a crazy idea at the time that he did,” Tracy Berg said. “The answer was myocardial preservation. He couldn’t figure out how to develop that blue baby procedure that his son needed to preserve his myocardium, but he could for everyone who was having a heart attack.”

“Myocardial preservation is obviously what Ralph understood very well, and I think that Everhart also understood that. They were worried about having the myocardium not leak the enzymes that you can track on a blood draw, so that it could become healthy again,” she continued. “That’s a lot of what the New England Journal of Medicine article shows, that if you get that clot out, bring blood supply in, those cardiac enzymes drop down to normal, the EKGs come down to normal.”

With Berg’s agreement, Everhart and a handful of cardiologists started doing urgent coronary angiography in patients having heart attacks to view potential blockages. It was done first on five patients, said Dr. Robert Hustrulid, a Spokane internist since 1971 who has written about the first bypass event.

The group learned they could do the heart catheterizations on the acute cases without harm, Hustrulid said, but Berg chose not to operate on the early patients because the anatomy wasn’t ideal for a bypass. The group handled its first emergency coronary artery vein bypass grafting for a 64-year-old man with acute myocardial infarction at Sacred Heart Medical Center, said a 1975 medical paper presented by Ralph Berg.

Hustrulid said Berg was in another surgery when Dr. Kendall got the call to operate on that first patient, who was scheduled for an elective heart catheterization during a morning when he ended up having a heart attack. That was unknown to the cardiologist who proceeded about two and a half hours later and found a critical blockage.

After that successful bypass, the patient left the hospital in good condition. It set a pattern to move ahead, as Berg and colleagues did more bypasses and saw a higher rate of success for heart attack victims than what commonly happened – they died, Tracy Berg said.

That decade in Spokane held other innovations, she said.

When the first U.S. trauma center opened in Baltimore during the early 1970s, she said leaders researched the only three trauma response models then in the nation, one being Spokane because of its pre-hospital care for heart attacks. Its protocols placed medications, oxygen and a radio on ambulances so crews could discuss the case with doctors.

Her cousin’s heart condition remains difficult to treat today, she said, but he had a 1980 procedure by a leading “blue baby” specialist in Alabama that extended his life by a decade. He died in 1991. She said her cousin’s surgery the same year as the scientific paper might explain why its significance isn’t widely known in Spokane. Ralph Berg, who died in 2017, was focused on his son.

Tracy Berg sharpened her book’s focus around 2010, after interviewing someone she described as an early critic of her uncle and the Spokane experience, Dr. K. Alvin Merendino, a former University of Washington chair of surgery and thoracic surgery.

When Tracy Berg told Merendino that her cousin was a blue baby with a complex transposition, she said Merendino broke down in tears.

“He did not know that Ralph Berg had a blue baby himself,” she said. “When he learned that, this was his quote, ‘Ralph Berg stayed in the game for Jason.’ “

“What references the game was the development of direct coronary bypass, which came in ‘68-’69 and was done in Spokane in ‘69 on chronic angina patients, and then Dr. Berg and Dr. Everhart started doing it on acute heart attacks, which was a radical idea at the time.

“If you can understand the pressure from parenting a blue baby with a doomed prognosis, you can understand why Ralph Berg said yes to that. And that launched the huge body of work called the ‘Spokane Experience.’ ”