We the People civics lesson: Why did the United States enter World War I?

Each week, The Spokesman-Review examines one question from the Naturalization Test immigrants must pass to become United States citizens.

Today’s question: Why did the U.S. enter World War I?

One hundred and four years ago, President Woodrow Wilson committed the United States to what was then the “world war.” The “why” of this decision, like the war itself, defies simple explanation. But it is an important question. The decision for war became a defining moment in the outcome of the conflict and in America’s role in the world.

When war loomed in Europe in 1914, newspaper editors like Edwin B. Aldrich of Pendleton’s East Oregonian began educating American readers about the gathering storm. Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s assassination, Aldrich explained, came of a longstanding dispute between Serbia and Austria-Hungary. He outlined the competing alliances – France, Russia and Great Britain on one side, Germany and Austria-Hungary on the other. After Austria-Hungary’s declaration of war on Serbia activated those alliances, Aldrich foresaw the conflict becoming a “bloody whirlpool.” Indeed, it sucked in six continents and its first major battle resulted in 400,000 casualties.

Appalled by reports of brutal bloodletting, most Americans opposed intervention. Wilson urged them to remain neutral in their thoughts, for sound reasons. The U.S. had citizens with ties to all the warring nations. Nonintervention would position the country perfectly to broker a positive peace. Standing aside also promised to be profitable, as orders for war material and supplies poured in from the combatants. But there was a catch. In August 1914, the British Navy blockaded German ports. Henceforth, the U.S. would be supplying only Britain and France. Thus, U.S. neutrality had a tilt from the beginning.

Despite Americans’ best intentions, remaining above the fray proved problematic. Those convinced that the oceans protected them were sobered to see the Atlantic itself become a theater of war. By early 1915, Germany had countered the British blockade by establishing a war zone around the British Isles and unleashing its submarines to sink ships without warning. On May 7, 1915, the conflict hit home: 128 Americans numbered among the victims when a submarine lurking off southern Ireland torpedoed the passenger liner Lusitania. Despite several additional incidents, Wilson remained determined to avoid war. In the Sussex Pledge of May 1916, he successfully pressured Germany, whose leaders did not then want a break with the U.S., to renounce sink-on-sight operations.

Throughout 1915-16, the U.S. faced domestic challenges to its non-interventionism. Former President Theodore Roosevelt loudly and publicly inveighed against Wilson for failing to stand up to German aggression and championed the “Preparedness” movement, which aimed to ready American youth to respond when, not if, war came. Meanwhile, the country was rattled by several sensational crimes suggesting German saboteurs at work.

On July 3, 1915, German-born professor Frank Holt tried to kill prominent banker J.P. Morgan, protesting Morgan’s role in financing the French and British war effort. Holt was later tied to a bomb plot at the U.S. Capitol. Two million pounds of Britain-bound munitions in Jersey City, New Jersey, ignited in a spectacular explosion on July 30, 1916. Authorities suspected, but could not then prove, German involvement. Even these dramatic events failed to move Wilson, who narrowly won re-election under the banner “he kept us out of war.”

This claim proved short-lived.

As 1917 dawned, the German government faced a stalemate on the battlefield and severe blockade privations at home. It decided on a go-for-broke strategy, reauthorizing its submarines to sink ships on sight. This risked war with the U.S., but officials now believed they could knock Britain out of the war before the U.S. could mobilize. Besides, in their view, the U.S.’s ‘tilted’ neutrality had made the country a de facto enemy combatant.

Wilson still hoped for a diplomatic solution – until British intelligence shared a decoded telegram from German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmermann to the Mexican government. Zimmermann offered the return of territory lost in the 1846-48 Mexican-American war in exchange for an alliance with Germany. This trespass on American sovereignty finally convinced the president that no peaceful resolution was possible.

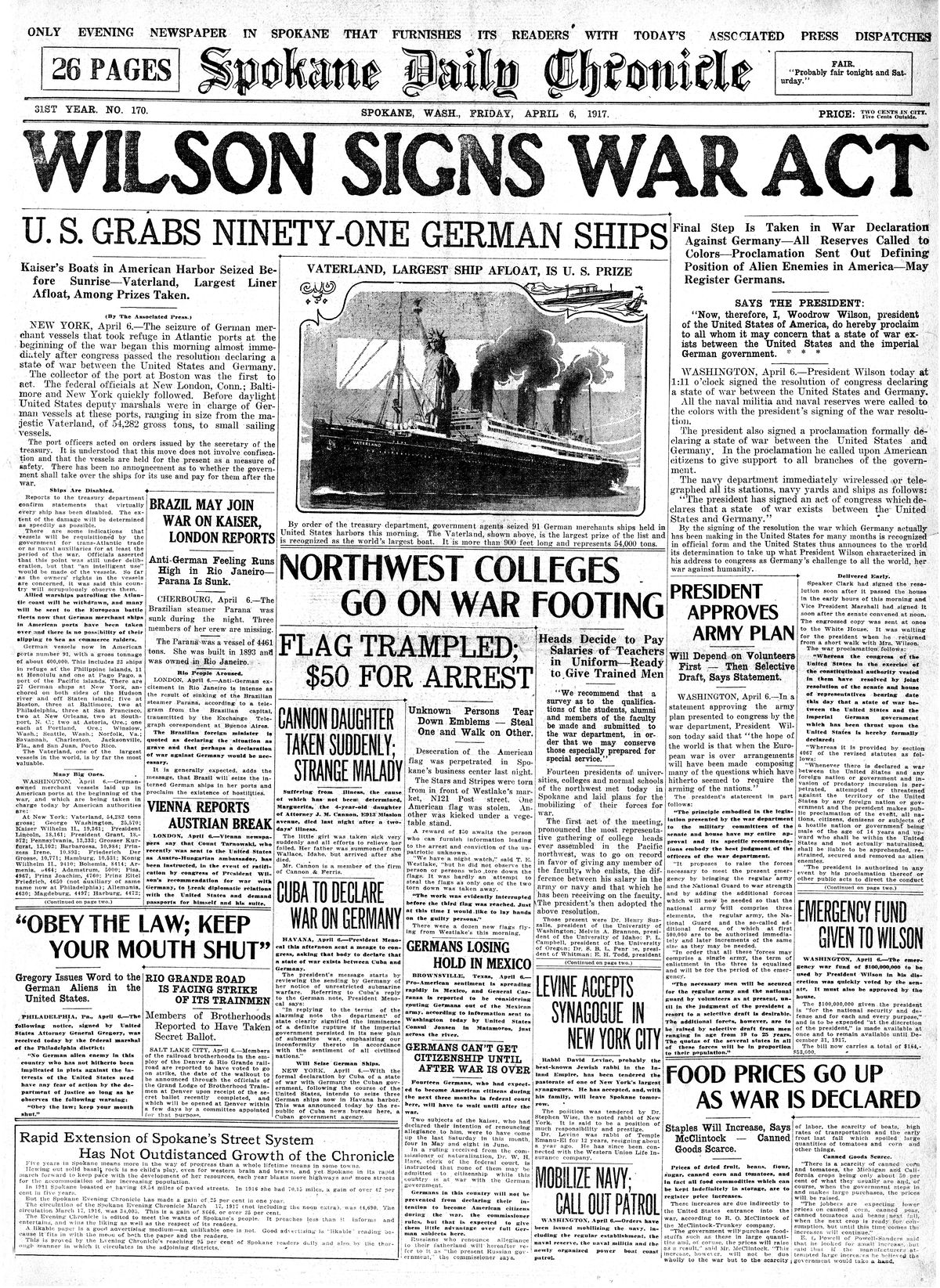

Wilson asked Congress for a declaration of war with Germany on April 2, 1917. Although the U.S. had now formally taken sides, he framed his decision in idealistic terms never before heard in wartime. The U.S. had no territorial pretensions, he declared. It entered the war in hopes of crafting a just and lasting peace, of making the world “safe for democracy.” As the country mobilized, Wilson fleshed out his vision in his 14 points, a blueprint for the peace that included a League of Nations, a deliberative body that would sort quarrels between nations before they morphed into war.

By November 1918, the promise of a generous peace, plus the apparently limitless supply of men and material the U.S. brought to the war, moved the German government to request an armistice.

The ensuing Versailles peace settlements disappointed. Germany alone was blamed for the war, and conflicts of interest among the peacemakers ensured democracy became a reality only in Europe for peoples allied with the victors.

The American people compounded the disappointment when their elected representatives refused to ratify the peace treaty or join the League of Nations. Unprepared for the responsibilities of leadership, the U.S. turned its back on Wilson and the broken world of 1919.

The decision for war in 1917 came primarily from Germany’s refusal to honor the U.S.’s compromised neutrality. The long-term significance of the U.S. entry is profound. It marked America’s debut as a world power and helped end the war. The pro-democracy rhetoric in which Wilson couched his justification became a template for future presidents faced with conflicts hot and cold. It is on display notably in Franklin Roosevelt’s Atlantic Charter, Harry Truman’s ‘containment’ speech, John F. Kennedy’s inaugural address and George W. Bush’s speech announcing war with Iraq.

Moreover, the U.S.’s 1919 rejection of postwar leadership represented an important lesson for its leaders after World War II. They did not walk away from the carnage, instead seizing the moment to create institutions and programs – the World Bank, the United Nations, the Marshall plan – that did not end war, but certainly brought about a safer, more secure world.

Brigit Farley is an associate professor of history at Washington State University in Pullman.

This article is part of a Spokesman-Review partnership with the Foley Institute of Public Policy and Public Service at Washington State University.