Holocaust survivors use social media to fight anti-Semitism

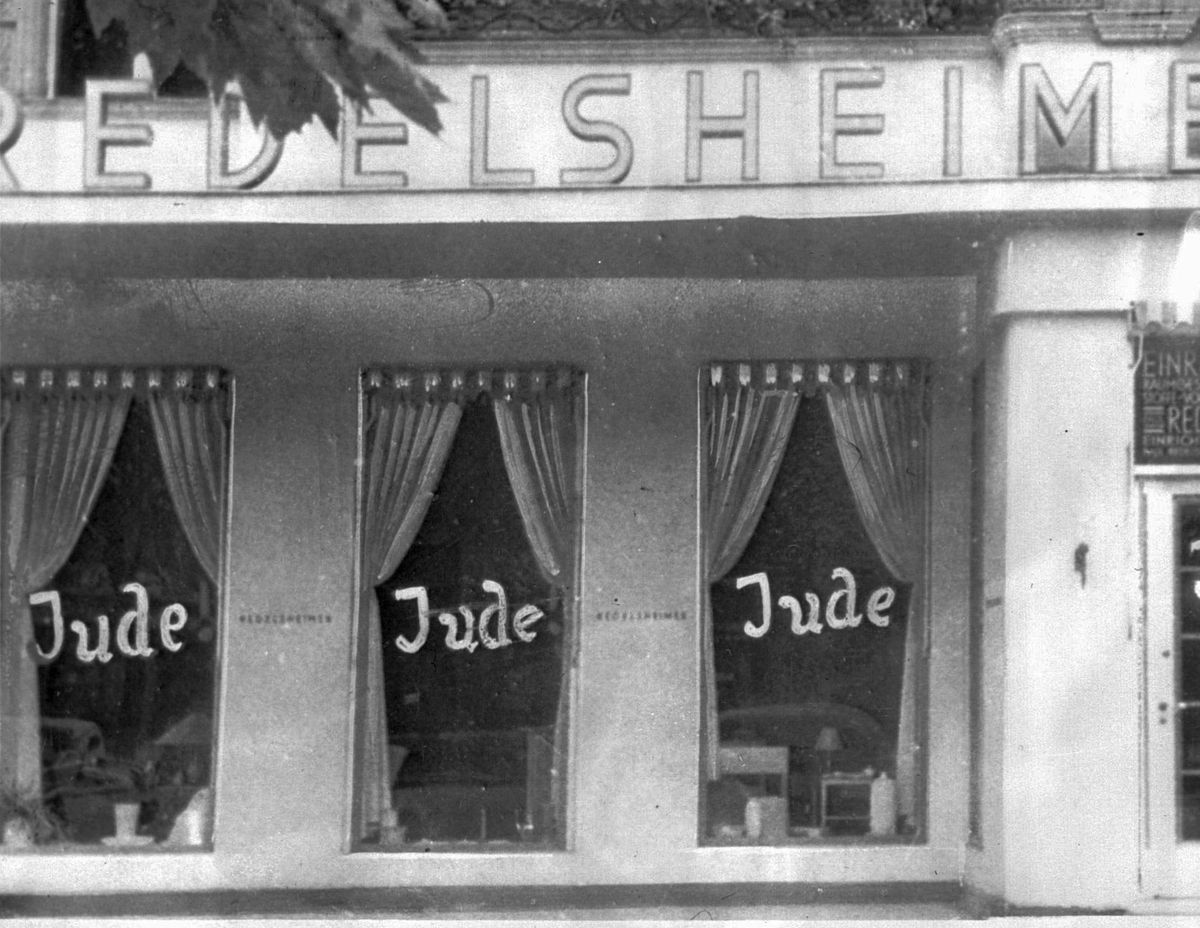

FILE - In this Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2014 file photo, the Yellow Star badge of Heinz-Joachim Aris (Dresden 1941) reading 'Jew' is displayed in a showcase during a press preview in the new special exhibition 'Shoes of the Dead - Dresden and the Shoah' at the Military History Museum in Dresden, Germany. Before local anti-Jewish laws were enacted, before neighborhood shops and synagogues were destroyed, and before Jews were forced into ghettos, cattle cars, and camps, words were used to stoke the fire of hate. 'ItStartedWithWords' is a digital, Holocaust education campaign posting weekly videos of survivors from across the world reflecting on those moments that led up to the Holocaust. (Jens Meyer)

BERLIN – Alarmed by a rise in online anti-Semitism during the pandemic, coupled with studies indicating younger generations lack even basic knowledge of the Nazi genocide, Holocaust survivors are taking to social media to share their experiences of how hate speech paved the way for mass murder.

With short video messages recounting their stories, participants in the #ItStartedWithWords campaign hope to educate people about how the Nazis embarked on an insidious campaign to dehumanize and marginalize Jews – years before death camps were established to carry out murder on an industrial scale.

Six individual videos and a compilation were being released Thursday over Facebook, Instagram and Twitter, followed by one video per week. The posts include a link to a webpage with more testimonies and teaching materials.

“There aren’t too many of us going out and speaking anymore, we’re few in numbers but our voices are heard,” Sidney Zoltak, an 89-year-old survivor from Poland, told the Associated Press in a telephone interview from Montreal.

“We are not there to tell them stories that we read or that we heard – we are telling facts, we are telling what happened to us and to our neighbors and to our communities. And I think that this is the strongest possible way.”

Once the Nazi Party came to power in Germany in 1933, its leaders immediately set about making good on their pledges to “Aryanize” the country, segregating and marginalizing the Jewish population.

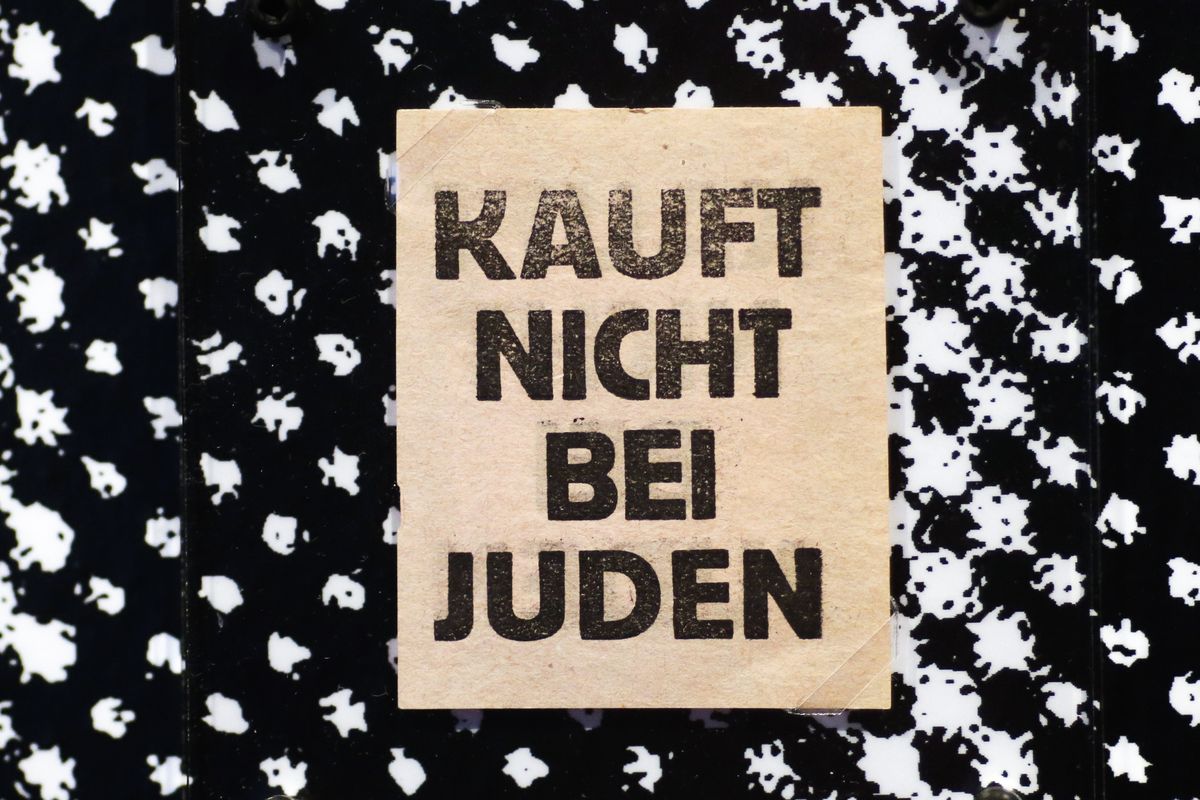

The Nazi government encouraged the boycott of Jewish businesses, which were daubed with the Star of David or the word “Jude” – Jew. Propaganda posters and films suggested Jews were “vermin,” comparing them to rats and insects, while new laws were passed to restrict all aspects of Jews’ lives.

Charlotte Knobloch, who was born in Munich in 1932, recalls in her video message how her neighbors suddenly forbid their children from playing with her or other Jews.

“I was 4 years old,” Knobloch remembered. “I didn’t even know what Jews were.”

The campaign, launched to coincide with Israel’s Holocaust Remembrance Day, was organized by the New York-based Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, which negotiates compensation for victims. It is backed by many organizations, including the United Nations.

It comes as a study released this week by Israeli researchers found that coronavirus lockdowns last year shifted some anti-Semitic hatred online, where conspiracy theories blaming Jews for the pandemic’s medical and economic devastation abounded.

Although the annual report by Tel Aviv University’s researchers on anti-Semitism showed that the social isolation of the pandemic resulted in fewer acts of violence against Jews across 40 countries, Jewish leaders expressed concern that online vitriol could lead to physical attacks when the lockdowns end.

Supporting the new online campaign, the International Auschwitz Committee noted one of the men who stormed the U.S. Capitol in January wore a sweatshirt with the slogan “Camp Auschwitz: Work Brings Freedom.”

“The survivors of Auschwitz experienced first-hand what it is like when words become deeds,” the organization wrote. “Their message to us: do not be indifferent!”

Recent surveys by the Claims Conference in several countries have also revealed a lack of knowledge about the Holocaust among young people, which the organization hopes the campaign will help address.

In a 50-state study of Millennials and Generation Z-age people in the U.S. last year, researchers found that 63% of respondents did not know that 6 million Jews were killed in the Holocaust and 48% could not name a single death camp or concentration camp.