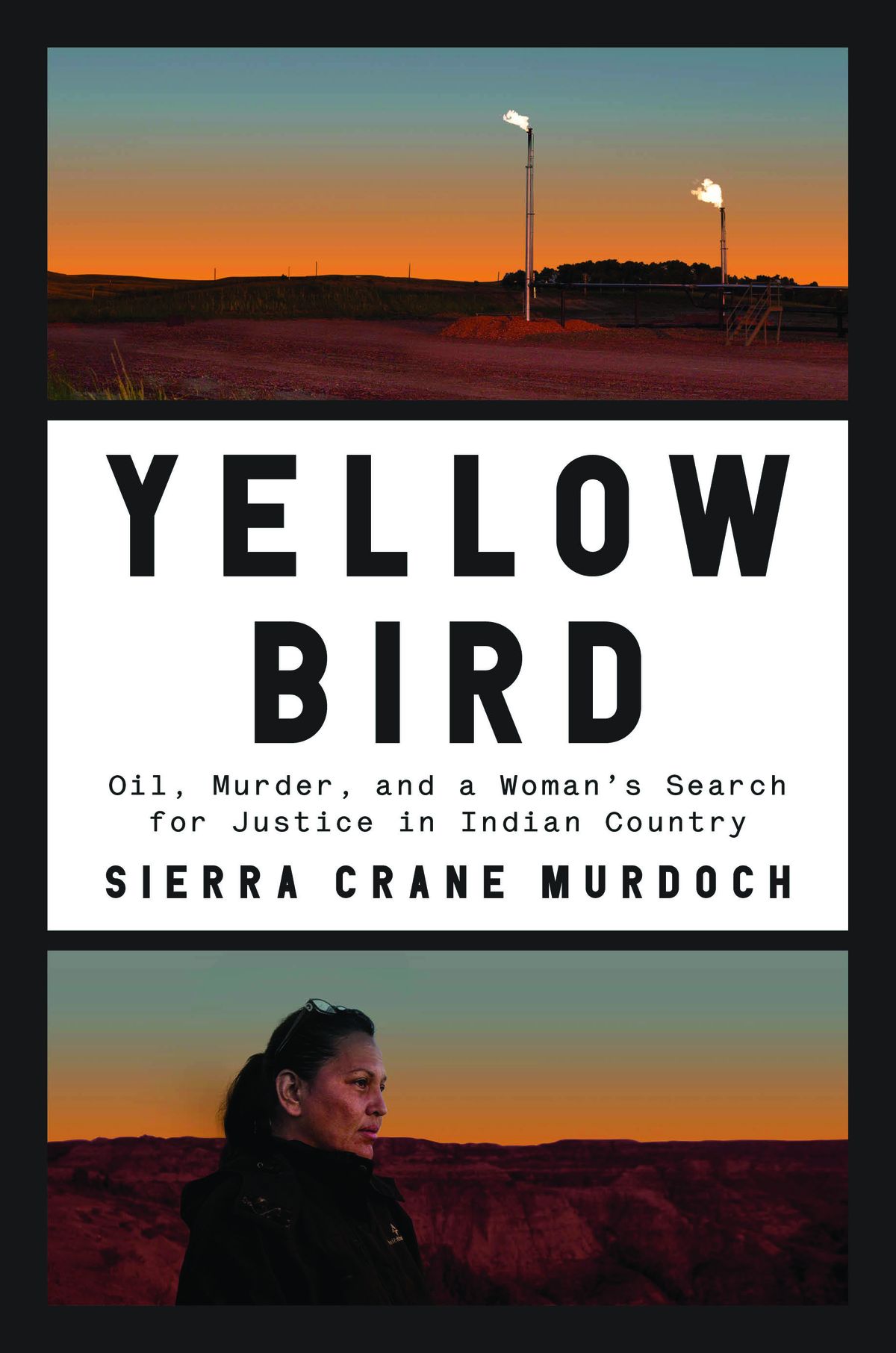

Sierra Crane Murdoch to discuss ‘Yellow Bird: Oil, Murder, and a Woman’s Search for Justice in Indian Country’

For journalist Sierra Crane Murdoch, what started as a magazine article about a tribal election on the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation became the jumping-off point for a novel-length true-crime account when she met Lissa Yellow Bird.

Murdoch will discuss her book, “Yellow Bird: Oil, Murder, and a Woman’s Search for Justice in Indian Country,” with The Spokesman-Review’s Shawn Vestal in a virtual event hosted by Auntie’s Bookstore at 7 p.m. Saturday.

Yellow Bird is a member of the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation, and also is, to an extent she can hardly explain herself, an amateur detective. After her 2009 release from prison, Yellow Bird returned to her home on the reservation.

In her absence, the cultural and economical fallout brought on by the Bakken oil boom was still seeping into the land. Outside corporate interests had begun corrupting tribal government while violence and addiction burned their way through the community.

In 2012, a young white oil field worker named Kristopher Clarke went missing without a trace. Clarke disappeared from his worksite after a conversation with his then-boss, James Henrikson.

“It’s not a crime to go missing,” was a common refrain. But, something about the case and Henrikson’s involvement gnawed at Yellow Bird. So, with the same obsessive dedication she was prone to in other areas of her life, she spent the next several years searching for a man she had never met.

The case took a turn to Spokane in 2013 when South Hill businessman Doug Carlile was shot and killed in his home. After Carlile’s death, evidence overlapping with that of the Clarke case came to light, and detectives were finally able to bring in Henrikson.

“Yellow Bird: Oil, Murder, and a Woman’s Search for Justice in Indian Country” follows Yellow Bird’s investigation as she navigates between the world of her tribe, transfigured by oil money, and the world of the non-Native, less-than-fortunate men flocking to the oil fields for a chance at striking rich in perhaps the only way left to them.

Throughout the writing process, Murdoch – who has written for the Atlantic, the New Yorker online, Virginia Quarterly Review, Orion and High Country News – was conscious that she was a white journalist telling a Native woman’s story. But she also was the only outsider journalist who had spent the necessary time in the community.

And, by the time Clarke disappeared, Murdoch had already spent years reporting on the reservation.

“I had already spent a lot of time there and kind of understood the ways that certain storylines connected,” Murdoch said. “I knew a lot of the people who were involved in the crime, (and) I already had a sense for the political, social and economic dynamics of the reservation where this played out.”

Still, she spent a great deal of time asking herself whether it was a story she had any right to tell.

“It’s not mine, it’s Lissa’s,” she said.

Yellow Bird is a member of a Native American tribe, and she also is an American citizen. This dual identity was something Murdoch had to work to understand as she came to know Yellow Bird and her family. Even after the book’s publication, they have remained close. At the time of this interview, Murdoch was just finishing her first visit with the Yellow Birds since the pandemic began in February.

“I believe in the practice of journalism, in writing stories about people and communities that are not our own, and I think that practice is essential,” Murdoch said. “At the same time, throughout this process as I began to understand my own role in this story, I really came to feel that journalists also have a responsibility to think about their place in the story, (that) our biases may cloud and even falsify other people’s truths.”

To this end, Murdoch made an extra effort to include Yellow Bird in the project, allowing her to read drafts and make editing requests – an uncommon practice, she said.

“I felt an obligation, but I also felt a desire for her to really participate in that process to a degree that I would not have asked of someone otherwise,” Murdoch said, recalling moments where Yellow Bird would encourage her to double down on the more difficult aspects of her story. “She’s … so unashamed of her own story.”

Murdoch hopes that readers come away with a new sense of the interconnectivity between communities on and off reservation land.

“A lot of non-Native Americans think of reservations as being these isolated places that operate in isolation from the rest of America,” she said. “And that’s simply not true. We are living out the legacy of our violence, and that violence is continuing to happen on the margins of Native and non-Native communities around … access to Native American land and indigenous resources.”

For more information about the event, visit auntiesbooks.com. A Zoom link will be posted.