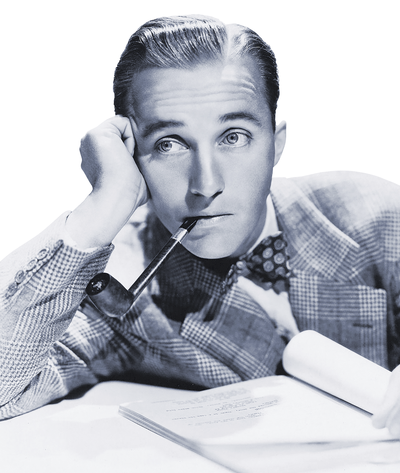

Bing Crosby’s lasting legacy in Spokane

Though he was born in Tacoma and moved to Los Angeles in 1925, Spokane has always been proud to call Bing Crosby one of our own.

Crosby moved to Spokane at the age of 3. He enrolled in Webster Grade School in 1908. Two years later, a neighbor, Valentine Hobart, began calling Crosby, born Harry, Bingo after the lead character in the comic “The Bingville Bugle.” Bingo eventually became Bing, and the name stuck.

Crosby played for the Webster baseball team and, at 13, became an altar boy at St. Aloysius Church.

Though he started performing at a young age, Crosby, after graduating from Gonzaga High School, enrolled in Gonzaga University with his eyes on law school. He did find time to perform in quite a few plays in high school and college and eventually connected with Alton “Al” Rinker, who invited Crosby to join his group, the Musicaladers.

The group proved to be quite popular, performing at Odd Fellows Hall, the Elks Club, the Manito Park Social Club and the Pekin Café. The Musicaladers became so popular, in fact, that Crosby realized he could make more money performing than at a law office. Crosby dropped out of college, and the Musicaladers began performing at Lareida’s Dance Pavilion in Dishman.

By spring 1925, the Musicaladers had broken up, though Crosby and Rinker began performing at the Clemmer Theater, now known as the Bing Crosby Theater. The pair performed for five months before heading to Los Angeles to seek fortune and fame.

Of course, Crosby found just that, but he never forgot about Spokane.

He returned to the city for the first time in 12 years in 1937 to receive an honorary doctoral degree from Gonzaga and the key to the city, participate in a couple of performances, judge a talent contest and attend a Gonzaga football game, during which he presented the team with a $1,000 water cart.

In 1949, Crosby returned to Gonzaga to make a donation to the school’s engineering building. In 1950, he brought his sons with him for a benefit at Gonzaga High School, and in 1951, he was the guest of honor at Gonzaga’s alumni luncheon.

Crosby was in town in 1957 when Gonzaga’s library, which he helped fundraise for, was dedicated to him and his family, and in 1968 when he presented the school with a microfilm research collection and three microfilm machines.

While Crosby died in Spain in 1977, it’s difficult to miss his lasting influence on Spokane.

There’s, of course, the Bing Crosby Theater, which received that name in 2006. There’s also the Bing Crosby Holiday Film Festival presented by the Bing Crosby Advocates.

The Crosby Library is now the Crosby Student Center and features a statue of Crosby in front of the building. Plus, Crosby’s childhood home is located at 508 E. Sharp Ave.

The home, which was built by the singer’s father and two of his uncles, now holds the Bing Crosby House Museum.

The museum is free to visit, though it is currently closed due to the coronavirus pandemic. Once it reopens, visitors can learn about both sides of Crosby.

Half of the museum is dedicated to Crosby as a singer, actor and performer. The walls are lined with gold records, awards and sheet music from Crosby’s films, which he sent to Gonzaga throughout his career. There also is a cardboard cutout of Crosby next to the Oscar he won for playing Father Chuck O’Malley in “Going My Way.”

The other half of the museum is dedicated to Crosby’s life as a husband and father. There are pictures of Crosby with his four sons from his first marriage to actress/singer Dixie Lee and Crosby with his three children from his second marriage to actress Kathryn Grant.

According to a book by Gary Crosby, Crosby’s oldest son, Crosby was mentally and physically abusive, so take those images with a grain of salt. For the record, Crosby’s son Phillip, while not denying that Crosby was strict, called the book a grab for publicity.

Despite what may have happened behind the scenes, Spokane is still fond of Crosby years after his death. When speaking to The Spokesman-Review in 2017, Bing Crosby House Museum docents Judy Boyer and the late Ellen Robey cited Crosby’s music and films, especially his “Road to …” series with Bob Hope, and the singer’s love for his adopted hometown as the reason why.

“Entertainers (from Spokane)? Not so much,” Robey said. “That’s why he stands out.”

“Local boy makes good is what it is,” Boyer added.

And just in time for the first snowfall of autumn 2020 in Spokane and heading toward a white Christmas, Crosby’s 1942 recording of “White Christmas” is one of the biggest selling singles of all time.

For links to more information about Crosby’s relationship with Spokane, visit gonzaga.edu/student-life/arts-culture/crosby-museum.