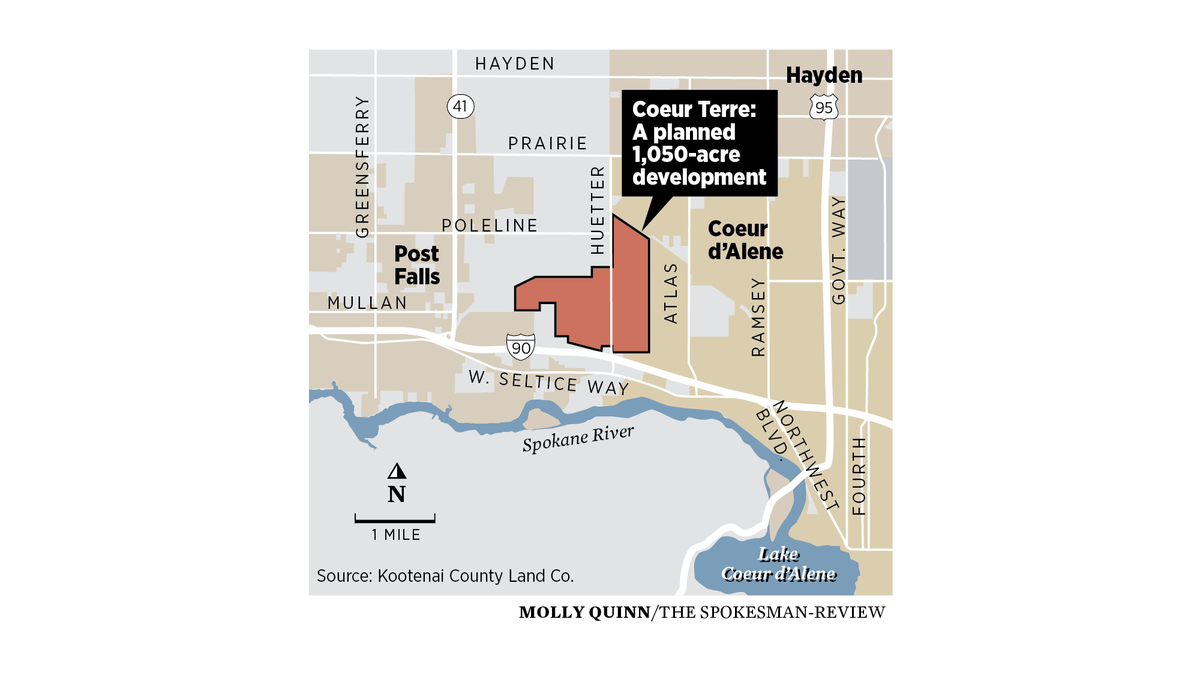

With new 4,500-unit development coming, can Kootenai County harness growth that could put population above 300,000?

A thousand acres of farm land, much of which is seen in this photo looking northwest near Huetter Road and Mullan Road, between Coeur d’Alene and Post Falls, may soon to be developed in Kootenai County. (Jesse Tinsley/The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

The intersection of Huetter and Mullan roads in Kootenai County has all the superficial hallmarks of the rural West: bucolic hayfields with mountains in the distance; a weathered wooden house with boarded-up windows; a dirt lot crowded with tractors, combines and other towering farm implements.

But this literal crossroads may also be a figurative one, a place where long-accumulating growth in the county’s population could begin to move in a different direction.

For one thing, some 1,050 acres of what are now agricultural fields rolling out in all directions from this intersection will soon be one of the largest developments in the county: the estimated 4,500-residence Coeur Terre.

When completed over the next 15 to 20 years, it will be home to some 11,000 people – a significant single contribution to the more than 165,000 new residents the Kootenai Metropolitan Planning Organization expects to flood into the county by 2040, just about doubling the county’s population to some 307,000.

A thousand acres of farm land, seen of which is seen in this photo looking west on Mulland Road near Huetter, between Coeur d’Alene and Post Falls, may soon to be developed in Kootenai County. (Jesse Tinsley/The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

And if voters approve a local vehicle registration fee in next month’s election and the remainder of the project’s $300 million price tag comes through, it may not just be the land on either side of Huetter Road that’s transformed. It may also be the road itself, which KMPO intends to turn into a four-lane freeway that would run in a 16-foot depression from a new interchange on Interstate 90 to the intersection of U.S. Highway 95 and state Highway 53.

The changes taking shape at the Huetter-Mullan intersection are the result of forces that have been building for decades, as the county’s population has grown from about 30,000 in 1960 to 60,000 in 1980 to 109,000 in 2000 to 150,000 in 2017.

But the area’s infrastructure and planning haven’t always kept up with the influx of new residents, as anyone trying to turn left onto Highway 53 from downtown Rathdrum at rush hour – to take one example of many – can attest .

As the county, its cities and its towns prepare for the next wave of growth, government officials and private developers are implementing and considering new approaches to manage and harness the expected changes.

‘End in mind’

Jason Kindred used to drive combines, cutting hay in what was then the expansive agricultural land of Spokane and Kootenai counties.

But on a recent afternoon, he was with his colleagues from Lakeside Capital Group – a Spokane-based investment firm with agricultural, industrial and real estate subsidiaries – in a sleek Coeur d’Alene conference room, discussing plans to gradually convert what has long been the Armstrong farm into a home for some 4,500 families, complete with a dog park, pickleball courts and casting pond, according to preliminary plans.

With his background working in both agriculture and development in the area, Kindred takes a long view of where the farm’s change fits into the bigger picture.

“This has been going for 20 years,” he said of housing development replacing rural land in his home region. “It’s not new. But we take the responsibility of that land very seriously.”

Kindred is the chief operating officer of Architerra Homes, a Lakeside subsidiary that builds homes for the subdivisions of another Lakeside subsidiary, Kootenai County Land Company.

Kootenai County Land Company has been acquiring land since 2012 and is behind a number of area projects, including the Reserve and the Foxtail Community in Post Falls, and is a “completely vertically integrated” operation, according to President Melissa Wells. That means, in short, that the various Lakeside subsidiaries allow the firm to do everything from surveying the land to building the homes in-house.

Their goal, like all developers, is to “provide homes for those people” who are coming to the area, Wells said.

But in so doing, the company has assumed duties that may seem unlikely for a developer of suburban housing, such as building trails, constructing playing fields and donating land for the new Treaty Rock Elementary School in the Post Falls School District.

Such arrangements are crucial in Kootenai County, where land values are high and no countywide growth management plan exists, making it difficult to acquire and protect land for public uses.

The need to work with private developers to create such public amenities is especially acute when it comes to schools, since no state funding is available to build them.

“So every penny we spend to build a new school would need to come from a local property tax bond measure,” said Scott Maben, director of communications for the Coeur d’Alene School District.

Donated land helps cut the cost for the district, and since new developments amplify the need for new schools, cities can negotiate with developers in the annexation process to include land for schools in their proposals.

Dena Naccarato, superintendent of the Post Falls School District, echoed that point in an email.

“Unlike Washington,” she wrote, “building schools in Idaho is incredibly challenging because it requires a super-majority vote by the community and the taxpayers bear the burden of the construction cost.”

Naccarato said a development as large as Coeur Terre “will most definitely create a need for schools” and that a school site was on a proposal Kootenai Land Company presented to the district last year.

It’s likely, though, that kids in the development would be split between the two districts, as Huetter Road is a “hard boundary” between them and won’t be reconsidered, according to Maben.

Huetter Road is also the boundary for a more fluid designation: the two cities’ areas of city impact.

Area of city impact is a concept enshrined in Idaho state law. It refers to land currently outside a city’s limits “where we expect growth to happen and annexations to happen,” according to Sean Holm, a senior planner with the city of Coeur d’Alene.

Because Coeur Terre sits on county land that’s right where the Post Falls and Coeur d’Alene areas of city impact meet, Kootenai Land Company can request that either city annex it.

Wells and her colleagues at the Kootenai Land Company say no decision has been made. But while Bob Seale, community development director for Post Falls, said the developers have “given us nothing” specific about their plans, Holm said Kootenai Land Company has met with his department to talk “conceptually” about bringing the project into Coeur d’Alene.

Before that can happen, however, the city has to rewrite its comprehensive plan to include the portion of the Coeur Terre site that lies on the west side of Huetter Road and inside Post Falls’ area of city impact. And Kootenai Land Company has agreed to cover the cost of the city conducting that analysis, Holm said.

Both Holm and Seale used the same line – “Development pays for development” – to dispel the idea that either city would attempt to woo the developer with incentives. Instead, they said, the decision would likely come down to which city’s water, sewer and other infrastructure could be tapped into more economically.

Once that choice is made, the chosen city will have to decide whether it can handle the increased demand on its systems – and whether the cost of doing so will be offset by the incumbent increase in property taxes.

The decision about where Coeur Terre will end up – or rather, which city will grow to include it – is unlikely to be made until at least early next year, when Coeur d’Alene is expected to complete the requisite comprehensive plan update.

And details about what exactly the development will look like remain in flux. Even as Kindred, Wells and their colleagues showed off conceptual drawings of the development’s preliminary layout earlier this month, they insisted the project would remain open to changes that may occur over the perhaps two-decade timeline until completion.

Despite that commitment to adapt to changes in the housing market, they also argue the project’s strength lies in the coordinated, planned vision that will guide its construction.

As the project gradually takes shape over the years, Kindred said the company’s planners will be able to make decisions “with the end in mind” and will aim to end up with a coherent community.

Glenn Miles, executive director of the Kootenai Metropolitan Planning Organization, said he agrees that Coeur Terre’s large size “may not be necessarily a bad thing.”

Rather than the 1,050-acre farm being divided and developed as a series of “small, incremental chunks” by a series of different developers, as so often happens, Miles said “there may actually be a chance” to manage how streets, utilities and other infrastructure are put together at Coeur Terre.

With a process of “slow, incremental growth,” Miles said, “you know what you’re going to get when it comes.”

‘Some level of balance’

“Slow and incremental” is not how most observers would describe growth in Kootenai County, but Dave Callahan is hoping to bring a more deliberate, forward-looking approach to the county’s rapid population expansion.

Callahan is Kootenai County’s director of community development, and the county commissioners recently asked him to pursue a bureaucratic-sounding task that could have major implications on the ground: draft a white paper on growth management.

That report will seek to summarize what approaches to managing growth are available, how they’ve worked elsewhere and how they might be applied in Kootenai County.

Callahan, who is working with others in his department to draft the report, said he’s drawing on an extensive background in land-use planning that goes back to the 1980s. In particular, Callahan said his time working in Boulder, Colorado, has helped inform what he’s preparing for the commissioners.

Boulder County, he notes, has amassed some 100,000 acres of open space, despite its setting outside Denver, in one of the most rapidly growing parts of the country.

While emphasizing Kootenai County is “at a very early stage in these things,” Boulder County’s successful effort to acquire land and preserve it for public use is “one of the possible tools for dealing with growth in this white paper.” And it’s a tool, he said, that “I happen to like.”

He said open space acquisition can work especially well when combined with another planning tool: intergovernmental agreements between the county and its cities that mean “most new development would occur in the cities, where the infrastructure can handle it.”

In Boulder County, Callahan said, “those two things came together in a way that had symbiosis.”

As for Kootenai County, he said it’s “way too early to say what that (approach to growth management) will look like here, if it even gets traction.”

There are signs, though, that concern about the county’s growth is mounting among residents of the famously conservative county, according to Chris Fillios, chairman of the Board of Commissioners.

When the Republican was running in the primary election, his campaign’s Facebook page was getting 10 times as many hits and impressions when he posted on subjects related to growth than when the topic was taxes, Fillios said.

But while interest in the issue is on the rise, Fillios acknowledges there may be resistance among his mostly conservative constituency to the idea of government taking a more active role in land-use decisions.

Because Idaho is “a very strong” property rights state, Fillios said it may be “challenging” to convince people that a county growth management plan is the best approach.

“There are those who believe let the market take care of it,” he said. “There are those who believe we don’t need to plan. … Professional planners would not subscribe to that.”

As the county drafts a white paper and perhaps a growth management plan, Fillios said it will be important that it tries to balance property rights with other issues, such as infrastructure, development and the environment.

“It’s a question of how do we achieve some level of balance so that we can preserve a decent quality of life,” he said.

To achieve that balance, Fillios said, the county will have to look ahead, rather than simply responding in real-time to a rapidly changing landscape.

“If corporations can plan, if families can plan, why can’t government plan?” he asked. “If we don’t do something, (growth is) going to be haphazard. And if it’s haphazard it’s going to degrade the quality of life. … The time is now. It should’ve been done years ago, but we need to look at it now.”

Miles, of the Kootenai Metropolitan Planning Organization, said the same is true of the county’s transportation network: there’s a long list of work to be done not only to prepare for coming growth but also to catch up with decades of growth that has already occurred.

That’s why he supports the local vehicle registration fee on the November ballot, which would cost $25 a year for motorcycles and $50 for cars and trucks and which would be collected starting New Year’s Day through 2041.

The money would help fund a dozen projects, including the Huetter Bypass, a widening of I-90 to six lanes and improvements to numerous area roads. Those projects could cost an estimated $1.8 billion, and the fee would cover about 30% of the tab. That’s the threshold for the local funding required for KMPO to pursue many state and federal grants that could pay the rest.

Miles said the projects would address “what’s occurred since 1970, when the last improvements” were made to the local road system – and what’s expected over the next 20 years.

Meanwhile, the Idaho Transportation Department has begun work on a suite of projects on its system in the county, including creating a new interchange at state Highway 53 and U.S. Highway 95, which is on the brink of being complete; rebuilding state Highway 41, which is underway; and reconstructing the interchange connecting I-90 and Highway 41 a few years out.

As the county braces for the next burst in what has been a long cycle of growth, Callahan says it’s these kinds of forward-thinking changes that have the best chance of preserving the characteristics that draw so many to Kootenai County.

“Completely unchecked, completely unregulated growth tends to overwhelm the community,” Callahan said. “And the thing that brings people there is no longer there.”

What brings them to the county, said Seale, the Post Falls community development director and a North Idaho native, are things like clean air, clean water, proximity to nature and lighter traffic than the even more populated areas many of them come from.

As county planners work to retain those advantages, Callahan said his aim is not to “impose my own ideology anywhere … because I don’t really see this as much as an overarching government issue or planning issue as much as” an effort at “finding common ground.”

“The only question in my mind is, given what is,” Callahan said, “what might there be?”

‘The impact’

Jon Mueller tried to answer Callahan’s rhetorical question in the 2000s, when the now-retired landscape architect was serving his nine-year tenure on the Kootenai County Planning Commission, including four years as chairman.

At the time, he said, development was consuming about 1,000 acres of land a year.

“It wasn’t going to be long from where we were headed ‘til there wasn’t going to be any land left,” Mueller said.

Such concerns led to discussions “about ways to preserve land on the (Rathdrum) prairie” and to “create the means by which we could maintain the separation between cities” in order to preserve some of the rural character outside the cities “as well as an identity for those cities,” Mueller said.

The discussions led to progress in developing what was known as the Rathdrum Prairie Open Space Plan, which identified existing open space that could be targeted for preservation. The aim, Mueller said, was “maintain some semblance” of the county’s rural identity and to preserve rural values, “which I happen to think are important.”

That initiative fizzled, however, when the Great Recession hit in 2008 and “slammed the breaks on development,” along with the effort to manage it.

“Now, we’re seeing this accelerated growth again,” Mueller said, as well as a new effort to harness it, which he supports, despite his doubts about its odds of success.

“Do I think it’s important that we look somehow to preservation of open space? Absolutely,” Mueller said.

But does he think it will happen?

“Probably not.”

His pessimism is a result, in large part, of “the politics of the state,” where some 70% of the land is owned in some fashion by the public and the setting aside of additional lands “is a really tough thing to sell and to overcome, especially here in northern Idaho, which is very conservative,” he said.

Pointing to Boise and Missoula, however, he said efforts to conserve land have been “fairly significant” and have helped “mitigate the larger effects of growth” without stopping it.

The experiences of those cities show, he said, that “mechanisms are in place” to preserve growth, though he believes “we don’t have the matching political will to do it” in Kootenai County.

But it’s not only up to government, according to Mueller. He said developments like Coeur Terre that set aside land for parks, trails and other kinds of open space “give me hope.” Smaller developments that lack the resources and space to set aside land are tantamount to “death by a thousand cuts,” Mueller said, “because we don’t get a lot of collective set aside with smaller developments.”

Without action, concerns about the county’s ability to stave off congestion and preserve its quality of life are bound to continue to mount – as are concerns about the effect of growth on the environment.

The fate of the massive Rathdrum Prairie Aquifer, which spans some 370 square miles beneath North Idaho and Eastern Washington, has been of source of particular worry.

But Rob Lindsay, Spokane County’s water programs manager, says he’s worried less about the 10-trillion-gallon aquifer’s capacity and more about what development will do to the Spokane River, which is “intimately connected to the aquifer.”

“Where we’re going to see the impact,” he said, “is in reduced river flows and in particular in the late season, in August and September.”

That’s when Coeur d’Alene Lake is being held at its summer levels by the dam at Post Falls, when people are watering their lawns and when “water use in this area goes up by a factor of three or four.”

While that water is being pumped from the aquifer, he said studies and modeling suggest the river is constantly replenishing it.

“It’s thought that about half of the water in the aquifer comes from what infiltrates under the Spokane River between Post Falls and about Sullivan Road,” Lindsay said.

The effect is, as a result, more pronounced in Washington, where habitat for fish and other species can be harmed, where recreational opportunities may be diminished and where regulators have stopped issuing any new water rights on the river due to low flows. In Idaho, meanwhile, the Idaho Department of Water Resources is “ready, willing and able to continue issuing water rights for those uses,” Lindsay said.

“Two separate states, two separate regulatory structures,” he said. “And they’re not complementary in their approach. As a matter of fact, they couldn’t be much more opposite in their management philosophy.”