Native artist Diane Covington’s exhibit at Yes Is a Feeling highlights indigenous works

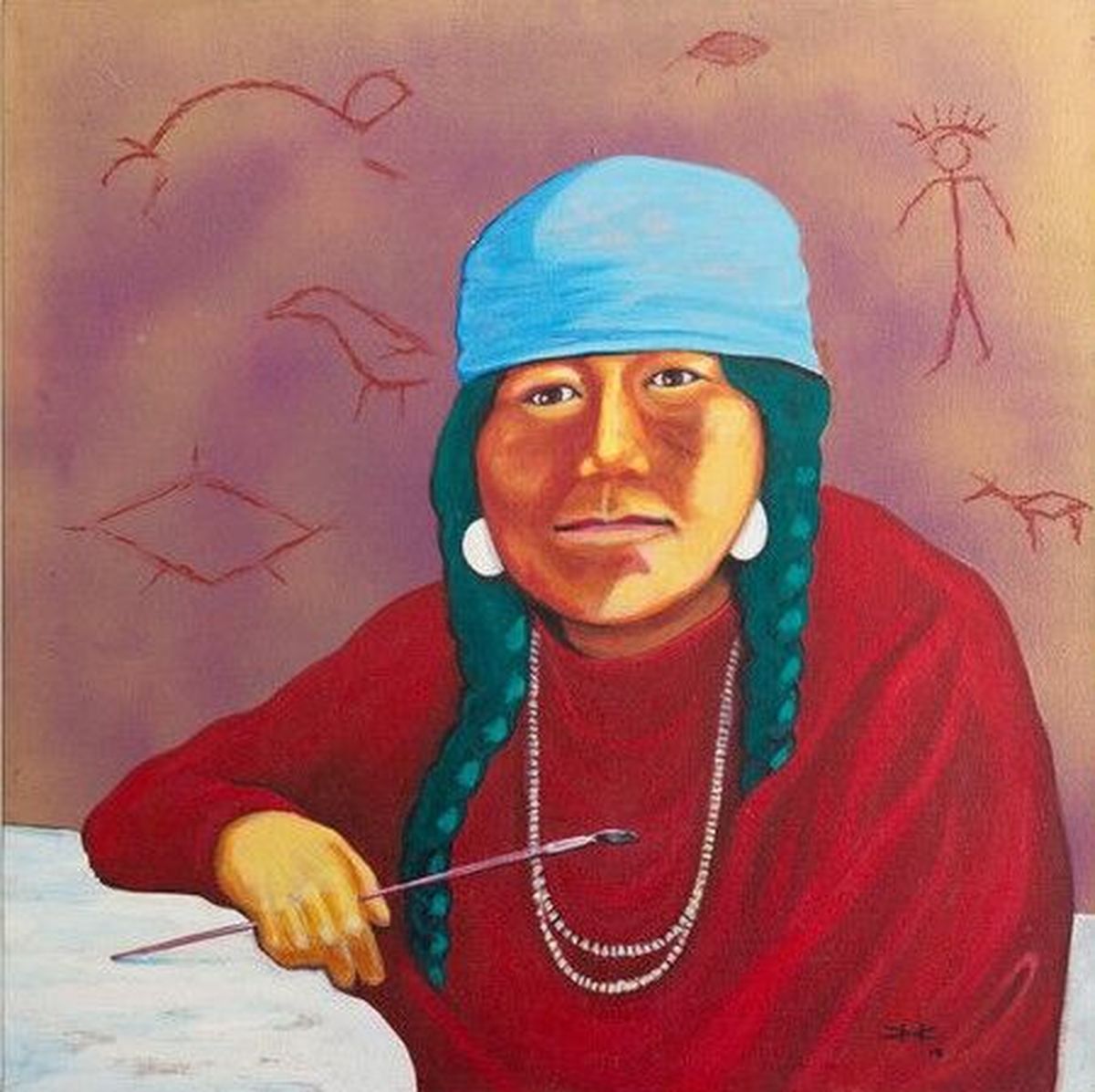

Artists take part in a recent “Eleven Gatherings Plateau Salish Art” workshop at Yes Is a Feeling art gallery in downtown Spokane. (Courtesy)

For local painter Diane Covington, Coyote has always been a trickster. In her world, Coyote is an anthropomorphic man whose antics and schemes often result in him becoming his own worst enemy.

Covington, 58, a member of the Sanpoil Band of Colville Confederate Tribes and Spokane Tribe of Indians, chose to focus on Coyote for a new series of artists’ workshops she launched last February.

Spokane Arts awarded her a grant to host the workshops throughout the year. She called the collaborative art sessions “Eleven Gatherings Plateau Salish Art.” Her goal for the gatherings was to encourage other Native Plateau artists to express themselves creatively.

Coyote seemed a good creative prompt with which to begin her first artists’ gathering, especially since it was the end of winter, a time reserved for many tribal members to tell Coyote stories. Little did Covington know that Coyote had more tricks and chaos up his sleeve.

“When we gathered at Yes Is a Feeling (art gallery) to share stories and paint Coyote, we didn’t know that our first in-person workshop would be our last due to COVID,” Covington said. “We didn’t know at the time that this entire year would be a trickster year.”

At 1 p.m. Sunday, Covington will finally show some pieces from that “Eleven Gatherings” workshop she hosted before the pandemic. The exhibition will hang in the Yes gallery in the Steam Plant downtown.

To allow social distance, the five pieces will be visible from the street by looking through the large window at 159 S. Lincoln St. From Nov. 22-28, the gallery will show more works created by Covington and other Native artists during quarantine in the same window in honor of Native American Heritage Month.

In the past seven months, perhaps all of humanity has learned that Coyote can wreak havoc and chaos. But through that upheaval, there are valuable lessons and growth, too. Since her ill-fated workshop launch in February, Covington is among thousands of local artists continuing to create art and discovering new ways to see and be seen.

“It’s been a time of growth, of changing points-of-view, learning how to communicate differently,” Covington said. “But we are still here.”

“We Are Still Here” has been a rallying cry of sorts for Covington since she first burst onto the Spokane art scene five years ago after a 15-year hiatus.

A self-dubbed late bloomer, Covington came up with the name for Spokane’s first “We Are Still Here Native Art Show” in 2015. The exhibit was conceived to highlight works of Native artists from more than a dozen tribes and hosted by Hatch: Creative Business Incubator in Spokane Valley. For Covington, “We Are Still Here” is a reminder, a declaration and an affirmation.

Native Americans are not the mythical “vanishing race” that white America has falsely described in yellowed photographs and feathered cliches. Tribal members, families and neighbors are still here, even thriving, and have new and interesting things to say. Covington’s continuing goal is to help those voices rise and be heard.

Covington grew up in Coeur d’Alene, Missoula and Spokane but moved away as a single mother to Michigan, where she was always the only Native American in the art classes she took there. She was thrilled to return to Spokane and take up painting again a few years ago and started showing her work as a self-described grandma-aged emerging artist.

But as an artist living in Welpinit on the Spokane reservation, she was disturbed to notice that there was little Native art to see in the Spokane area. The Native-themed shows she did find often featured the work of white artists rather than pieces done by Plateau Salish artists.

“I traveled to Seattle and Santa Fe and was thrilled at the indigenous art everywhere,” Covington said. “In stark juxtaposition, Spokane had very little representation from the Plateau Salish artists in the region, (such as) Spokane, Colville, Kalispel, Coeur d’Alene, Salish and Kootenai, and also many non-Salish tribes.

“I wondered why all of our own wonderful work wasn’t being celebrated in the place that we have been for millennia. It didn’t seem right.”

Yes gallery owner Roin Morigeau also noticed how Spokane failed to embrace its indigenous art and artists.

“Think of the cultural relevance that Seattle has to Coast Salish, Haida and various coastal tribal art – it’s everywhere,” Morigeau said. “Go watch any ‘Grey’s Anatomy’ episode. It’s used in nearly every frame to locate the series as being in Seattle.”

“Diane’s work asks the question: ‘Why doesn’t that exist here in Spokane?’ ” said Morigeau, who is a descendant of the Flathead Salish Tribe of Montana.

Morigeau is focused not only on the cultural significance, but also on the revenue lost to Native artists when private corporations co-opt Native designs and representations for non-Native retail shops and brands.

“These traditional designs that Urban Outfitters puts on a throw pillow aren’t merely aesthetic. They are stories and are used in very specific ways,” Morigeau said. “We have a responsibility to not only elevate this work but also to create sanctions to maintain ownership and control of revenue of this work back to the original artists.”

Since 2015, the atmosphere for Indigenous artists and peoples has been improving, not only locally, but all over the world, according to Covington.

“We are no longer waiting to be noticed. We are becoming more proactive,” Covington said. “Native people are learning their languages, their medicine and food ways, and we are expressing our indigenous selves through a variety of traditional and contemporary ways.”

Covington’s work centers around Native people reconnecting and expressing themselves artistically on their traditional homelands, of which the city of Spokane is part. The art that Covington first noticed when growing up in Spokane wasn’t fine art, modern art, renaissance art or the kind of art she studied at Spokane Falls Community College classes.

“The art I knew came from my grandma and other family in the form of beading, buckskin and leather work, feather and regalia work,” Covington said. “It is empowering for us to make and show our own work rather than being shown by others as if we only lived in the past.”

“Diane is pointing the spotlight on local, contemporary Native painters, from novice to working artists,” Morigeau said. “This window display is Diane saying, ‘We’re still here. Here we are.’ ”