Lifelong Spokane Valley resident Bert Porter ‘tried to make a difference’

Spokane Valley lost another piece of its history recently with the death of Bert J. Porter, a lifelong resident raised on his parents’ farm who would spend his later years giving back to the community where he grew up.

Porter died Nov. 4. He was 92.

Longtime friend Jayne Singleton, director of the Spokane Valley Heritage Museum, said Porter was a true farm boy. He was kind, with a generous heart and had good common sense.

“When I say Valley farm boy, that’s a compliment,” she said. “Bert lived the history that I love and we preserve at the museum. To get to know him was a delight.”

Porter was born in 1928 and grew up on a farm at what is now Fourth Avenue and Sullivan Road.

“He was born in a house on Fourth Avenue, which is gone now,” Singleton said. “They grew Hearts of Gold cantaloupe.”

He attended Vera Grade School and graduated from Central Valley High School. He earned a bachelor’s degree in pharmacy from Washington State University in 1950 and joined the U.S. Air Force a few months later. His first assignment was at Fairchild Air Force Base, but he was transferred to the Far East Air Force and served in Japan for several years. One of his jobs was to run the pharmacy specialist program, and he also taught classes.

Porter bought a pharmacy at Fifth Avenue and Thor Street in Spokane in 1958 and named it Porter Drugs. He ran it until 1976 and then again from 1988 to 1994. Along the way he served on boards, was a member of numerous clubs, including the Rotary and the Elks, and was an active member of the WSU Alumni Association. He also served on the board of the Spokane Valley Heritage Museum.

His son, John Soberg, said Porter always wanted to be involved in the community.

“He felt he needed to give something back,” he said. “He did his part and made his contribution. He tried to make a difference.”

Porter also supported a lot of charities, including the Red Cross, the Boy Scouts and the Spokane Humane Society, Soberg said.

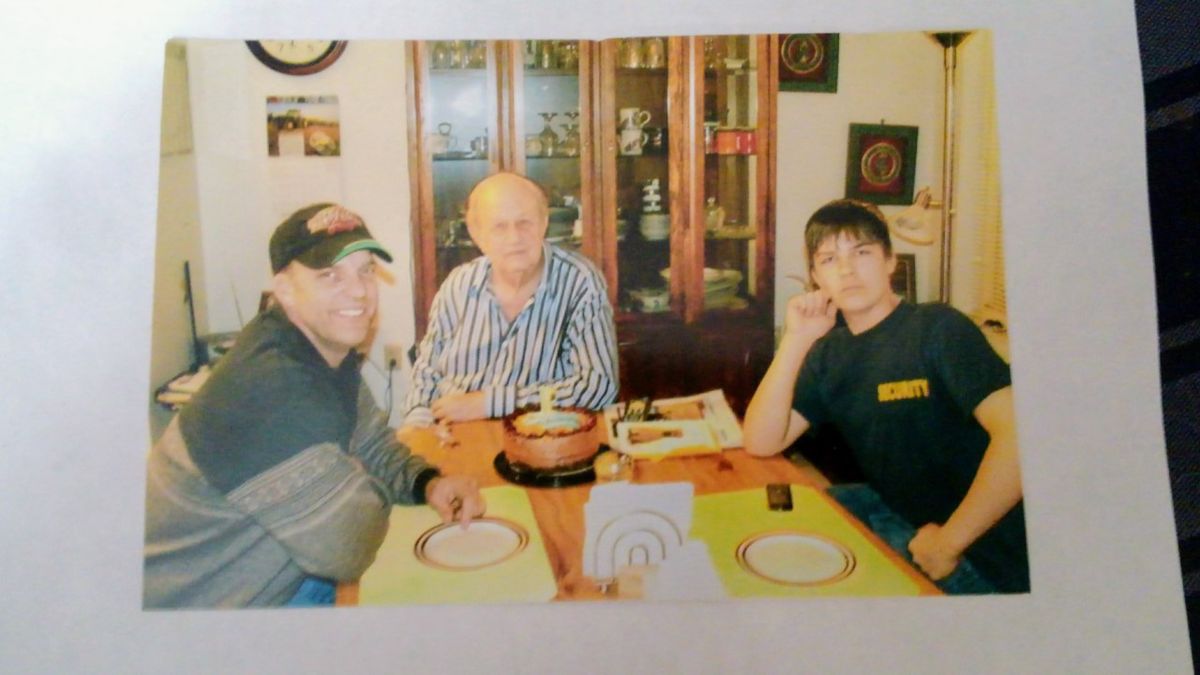

When his father was healthy, Soberg said they would go out to eat three or four nights a week.

“We really enjoyed each other’s company,” he said. “We used to talk a lot while we sat and played cards.”

The two usually talked to each other on the phone once a day. If Soberg didn’t call, his father would call the next day and jokingly inquire if he was OK because he hadn’t heard from him. Soberg said if he ever missed a day, it was usually because he was waiting for his father to call.

Once Porter found something that worked for him, he refused to change it. Soberg said he remembers going fishing with his father in his later years and giving him a flyrod to use.

“I cast his line out for him because he didn’t know how,” he said.

Porter insisted on pulling the line in by hand instead of reeling it in.

“He would pull it hand over hand,” he said. “Pretty soon he’d have a bird’s nest in his lap, nothing but fishing line. He had his own system.”

Singleton said she first met Porter at one of Spokane Valley’s first City Council meetings after the city incorporated. They chatted about the museum she wanted to open to preserve Spokane Valley’s unique history.

“We just kind of got to know each other over time,” she said. “He became involved in getting the museum going and growing.”

Singleton said it’s not uncommon for people to complain about things they didn’t like, but Porter didn’t just complain. He followed up with action. It wasn’t uncommon for him to call governors, senators or even the White House to make his views known, she said.

“He was very much an advocate,” she said.

Porter also loved to travel. “He traveled the world,” Singleton said. “He enjoyed learning about other cultures and other countries,” she said.

Porter was generous and gracious, Singleton said.

“On the personal side, he was like a father to me,” she said. “I was in my early 30s when I lost my dad.”

Singleton said she spent a lot of time with him in the last six months as his health failed.

“I enjoyed hearing his stories about the way Spokane Valley used to be,” she said. “His mind was always sharp.”

Soberg said his father’s health had been declining for a while. He was going to his father’s house daily to help care for him.

“This was a gradual thing,” he said. “He just got to the point where his body stopped working.”

On the day Porter died, he had shortness of breath and an erratic heartbeat. Soberg, not realizing his father was dying, took his father to the emergency room. Because of COVID-19 restrictions, he wasn’t allowed to stay with him. When hospital staff realized his father was dying, they called him and told him to come immediately. Soberg said he arrived 5 minutes after his father died.

He said he wishes he had made it back in time.

“He was dying and we didn’t see it,” he said.

Soberg said he’ll miss the daily phone calls with his father the most.

“I know I am who I am today because of his guidance and advice,” he said. “He made me want to be a better person.”

— Nina Culver can be reached at nculver47@gmail.com