Helga Estby’s long, long walk was almost lost to history

The Estbys' family home on Mallon Street, where they moved after losing the farm in Mica Creek, and where Helga wrote her lost memoirs. Photo courtesy of Linda Lawrence Hunt (Colin Mulvany / The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

In the later years of her life, Helga Estby would sit alone in her room and write the story of her long, long walk from Spokane to New York City.

It’s a nearly unbelievable tale, spilling over with adventure, heartbreak and social import, and Helga had hoped to make a book of it.

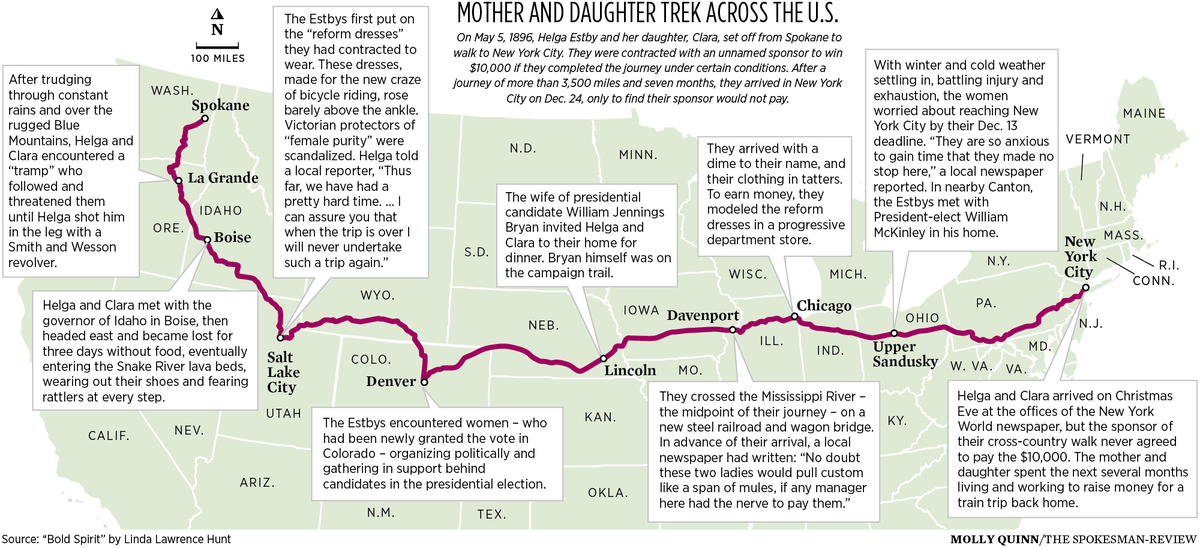

She and her daughter, Clara, walked the breadth of the nation in 1896 to try and save their family farm in Mica Creek – trudging over mountain passes and across lava beds and through deserts, stopping in cities to earn money and talk to newspaper reporters and meet with governors, all on the promise of a $10,000 payment from a sponsor in New York City.

Along the way, newspapers touted their exploits, and they became suffragette symbols of the “new woman.” Against all Victorian expectations and prejudices, Helga and Clara completed the journey of more than 3,500 miles, wearing out 32 pairs of shoes and occasionally wielding a pistol in self-defense.

It was a truly incredible tale, and it would be incredible to have Helga’s version of it now. But her long walk and her politics were unpopular with family members who had suffered through a diphtheria outbreak during her adventure – one that claimed the lives of two of Helga’s children and subjected the others to a brutal quarantine.

So the family banished the subject altogether during the years when Helga was writing her memoirs in an upstairs room of the family home on Mallon Avenue. It simply wasn’t spoken of.

After Helga’s death in 1942, her daughter Ida discovered hundreds of handwritten yellow pages filled with Helga’s story.

She burned them.

‘The devil’s agent’

One hundred and twenty-four years ago this month, Helga and Clara Estby arrived at the offices of The Spokesman-Review to announce that they planned to walk from Spokane to New York City.

An anonymous sponsor affiliated with “eastern parties” was said to have contracted to pay them $10,000 for the feat, which had just been announced in a New York City newspaper. Helga said she was making the journey to prevent the foreclosure of the Mica Creek farm that she and her husband, Ole, owned.

The Estbys were Norwegian immigrants who had first settled in Minnesota, then left to make their way in the rough-and-tumble boomtown of Spokane. But now, in the wake of the Panic of 1893, banks were failing, people were losing homes and families were desperate.

That was the context for Helga’s cross-country walk. From the start, however, her decision to leave Ole and seven children at home was seen by many, including her own family, as irresponsible and improper. Her place was with her children.

Although the journey’s sponsors remain unknown, the project was intended to promote a new vision of womanhood, one that showed women could be stronger and more capable than prevailing presumptions.

For example, the Estbys were to wear a new style of shorter skirt called a “reform dress” that had a hemline just above the ankle, instead of traditional floor-length Victorian dresses.

The reform dress was designed for riding a bicycle.

“Both the thought of women riding bicycles and daring such a radical change in dress met stiff resistance in some circles,” wrote Linda Lawrence Hunt, the Spokane author of “Bold Spirit: Helga Estby’s Forgotten Walk Across Victorian America.”

“The Rescue League of Washington formed to fight against women riding ‘the devil’s agent’ and wearing bicycle apparel.”

Hunt’s book is among the chief sources for this story, along with articles from Historylink.org, newspapers and magazines, and Helga’s great-granddaughter, Dorothy Bahr.

The uproar over bicycle skirts was but one example of the cultural context in which Helga, 36, and Clara, 18, set off from Spokane on May 5, 1896, intending to follow the rails by foot to New York City.

They carried a revolver, a “pepper gun” filled with cayenne powder, some medical supplies, a map and compass, a curling iron for Clara’s hair, a letter of introduction from the Spokane mayor and little else.

They planned to collect their money and be home by Christmas.

Floods and deserts

First came a May filled with rain, as they trudged through Washington’s wettest spring in 33 years and crossed the rugged Blue Mountains. Near La Grande, Oregon, they encountered a “persistent hobo” – in the words of Historylink.org – and Helga shot him in the leg.

When they came to the Idaho capital 30 days after their departure, they encountered a city desperate to contain the flooding Boise River.

The Idaho Statesman published a story about the women, and the Estbys also met the governor. Both activities would become hallmarks of the trip. Newspapers would write about every stage of their walk, and part of the sponsor’s contract apparently stipulated that the women meet with governors, perhaps as a way of putting reform dresses and reform ideas before key decision-makers.

After Boise, they decided to depart from the rail lines. This proved to be a mistake, as they found themselves lost in the lava plains of southeastern Idaho, dodging rattlesnakes for three days “without a mouthful of food,” Hunt writes in “Bold Spirit.”

Next they made for Salt Lake City and the silver mines outside of Park City. They spent three hungry days crossing the Red Desert of Wyoming and sleeping outdoors, then crossed the Laramie Mountains and walked six miles through a flooded river.

“Outside of Denver, a bold highwayman attempted to rob them,” Hunt writes in “Bold Spirit.” “Undaunted, Clara sprayed him with her pepper gun and ‘rolled him down a hill.’ ”

They often stayed in railroad section houses, though they were sometimes welcomed into people’s homes. In cities, they worked odd jobs, promoted their journey in the newspapers and sold photos of themselves to help pay the way.

Helga wrote letters home that did not survive.

They walked through Nebraska along the Platte River. In Lincoln, they had dinner with the wife of presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan. In Omaha, Clara fell ill and they were waylaid for several days in October – a significant problem, given that they had a Dec. 13 deadline for the $10,000 contract and a long way to go.

They reached the halfway point – the muddy Mississippi River in Davenport, Iowa – in mid-October. They arrived in Chicago, where they modeled reform dresses and met with the mayor, on Nov. 7. On Nov. 29, they met with President-elect William McKinley in Canton, Ohio.

They were rushing now, having covered more than 2,500 miles and with hundreds to go.

‘More villain than heroine’

On Christmas Eve, they finally reached Manhattan and the offices of the New York World newspaper, concerned that they had missed their deadline by nearly two weeks.

The newspaper had been the first to announce the news about their walk, and was perhaps involved in sponsoring the contest. It was common at the time for newspapers to pull various promotional stunts to attract readers.

The triumph of their accomplishment was short-lived.

The sponsor refused to pay the $10,000, or even train fare home, for reasons that may have included the missed deadline but which are unclear. Also, Helga and Clara lost a pocketbook with all their money and Helga’s trip journal.

Even as their arrival was being written up in newspapers all over the country – including back in Spokane, where the papers noted the “female globe-trotters” had left behind a husband to raise the children – it was coming to a ruinous conclusion.

They spent the next few months trying to work and save for a train trip back home.

Back in Spokane, meanwhile, as the one-year anniversary of their departure arrived, the Estby family was confronted with a harsh new challenge: Daughter Bertha came down with diphtheria. After a year of struggling to keep the farm and family afloat, this news was devastating, and it came on the heels of mounting scorn in the community and the family for what Helga had done.

Diphtheria was deadly, particularly in children, and highly contagious. Upon Bertha’s diagnosis, Ole Estby quarantined the other children in a shed. Fearing infection, he wouldn’t even take them blankets from the home.

Bertha died April 6, 1897. Ole approached the shed and shouted the heartbreaking information through the walls. Three days later, 9-year-old Johnny died of the disease as well, and Ole delivered the news in the same way.

When Helga learned about Bertha’s death, she made a public appeal for help to get home through the New York newspapers, and returned by train. She likely learned of Johnny’s death upon her arrival.

“She came home to Spokane more as villain than as heroine,” Hunt writes in “Bold Spirit.”

The disease and deaths of her children had hardened the disapproval of what she had done into bitterness that would last a lifetime for her surviving children.

And, after all that, the Estbys lost the farm in 1901. Ole went into construction and built the family a two-story home on Mallon. Helga became active in local politics. In 1913, Ole fell off a roof and died.

Helga’s daughter, Ida, and other family members moved in with her. She set up a room for herself where she began learning to paint, and started to write the story of her long, long walk.

She would later tell her granddaughter, Thelma, what she was writing.

“Take care of this story, honey,” she said.

‘I was electrified’

The silence that surrounded Helga’s story endured for years and years. Virtually everything Helga had that might have documented the walk was destroyed in that burn barrel in 1942 – but for a few newspaper clips that survived.

“We didn’t know about it until 1977,” said Bahr, Helga’s great-granddaughter. “My mother didn’t know about it at all.”

The first crack in the dam came in 1977, when her mother was given some newspaper clippings by an uncle. Those original articles formed the basis for a high-school paper written by Bahr’s daughter, Darillyn.

She got an A.

Seven years later, Dorothy’s son, Doug, wrote an essay about Helga for a state history contest – an essay that would spark the public restoration of Helga’s story.

Jim Hunt, Linda’s husband and then a Whitworth history professor, was a judge for that contest. One night in 1984, he was reading the entries in bed while Linda graded papers from her Whitworth English classes.

“He says, ‘Linda, you’ve got to read this paper,’ ” she said. “I was electrified. I had taught women’s history and I know what people assumed about women and their abilities at that time, and I thought: Who is this woman?”

She spent years and years finding as much of an answer as she could. It began with magazine articles, and became a doctoral project at Gonzaga University, and evolved into “Bold Spirit,” which was published in 2003.

The book represents a gargantuan research effort. The primary source – Helga herself – was missing, of course, and there was almost nothing in the historical record to help.

“To reconstruct any woman’s life from the 1890s is incredibly hard unless she left journals,” Hunt said. “Women’s stories were not valued highly.”

Hunt relied heavily on the many newspaper accounts of the journey, traveling to towns along the route, digging though archives and spooling through microfilm. She traveled to Norway and Minnesota to research the family history. She pulled together everything she could for what she called her “rag-rug history” – in reference to Scandinavian rugs that were made frugally from scraps of cloth.

The book received several awards, including the Washington Book Award, and a lot of attention in the press, from readers and schools, and elsewhere. Initially published by the University of Idaho Press, it was taken over by a Random House imprint, and continues to draw readers and attention.

Since “Bold Spirit” was published, Helga’s story has been written about in newspapers all around the world, including here. Two fictionalized accounts have been published. A graphic-novel-style telling of the story was published in the Inlander in 2015.

When the May 5 anniversary of the cross-country walk arrived this year, it was marked on social media by Historylink.org – the spark that prompted this story.

When Dorothy Bahr heard that a new story was being written about Helga’s once-forgotten adventure, she said, “Helga walks again!”

‘Helga’s eyes’

Helga’s descendants have come to embrace her story, of course. Dorothy and her husband, Daryll, now live in Spokane in a retirement community on the South Hill, where they have gathered clippings, photographs, family records and all manner of other material about Helga into binders several inches thick.

There are photos of a young Dorothy with Helga, on the porch of the home on Mallon, which is now gone – as is the Mica Creek farm. There are many, many family photos, and a wealth of news clippings. There is a copy of Daryllin Bahr’s 1977 history paper (“The big issue at the time was suffrage for women! Helga would march up and down with her little signs fighting for the right to vote.”)

And there is something unique: A first-person account from Helga – a letter, which came to light after “Bold Spirit” was published, that she had written to a Norwegian newspaper from New York. In it, she writes of going to the silver mine near Park City and riding down a crude elevator into the mine shaft with a foreman.

“When I said we were not afraid and were not going to be dizzy, he said that many men get so scared that they held tight; if they stagger to the side it would mean goodbye for them,” she wrote.

These days, Helga’s story is far from silenced, and her human legacy remains threaded throughout Spokane in the form of about a dozen descendants here.

Dorothy has a sister in Spokane, a brother in Grand Coulee, and other siblings around the country. Their son and his family live here, as well. One of their daughters, Katelyn Bahr, a Gonzaga Prep senior, is a Lilac princess.

“And she has Helga’s eyes,” Dorothy said.