Michael Jordan, documentary resonate with local basketball icons

Nineties nostalgia has helped mollify the famine in Hooptown, USA.

Two weekly episodes at a time.

A confluence of the basketball-stopping coronavirus pandemic and recent release of ESPN’s “The Last Dance” documentary has thrust Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls’ dynasty into Spokane’s consciousness.

Jordan – still widely believed to be the most powerful icon in sports – is the central figure in the in-depth series that ends Sunday night.

Its final two installments – Episodes 9 and 10 – will likely touch on the Bulls’ back-to-back finals wins over John Stockton (Gonzaga Prep, Gonzaga University) and the Utah Jazz in 1997 and 1998, the last of Jordan’s six titles.

From its candid interviews, never-before-seen footage, bumping soundtrack and conveyance of the deity-like figure Jordan was in the 1990s, “The Last Dance” has become America’s most-watched docuseries.

For a city that lost both the NCAA men’s and women’s tournaments it was set to host last March, experienced the first postponement of the world’s largest 3-on-3 basketball tournament, Hoopfest, and is void of what currently would be the NBA playoffs, “The Last Dance” has been a welcome distraction.

It has also reminded local basketball figures of their various run-ins with Jordan and the influence he had.

‘Meeting him was surreal’

Before point guard Matt Santangelo helped orchestrate Gonzaga’s program-changing run to the Elite Eight of the 1999 NCAA Tournament, few knew the four-syllable surname that still rings in Spokane.

Santangelo, the president of Hoopfest, was still a burgeoning talent, earning West Coast Conference Freshman of the Year in 1997 – the last time the Bulldogs were denied a postseason invitation.

It was around that time, though, when the Portland native was asked by then-Gonzaga coach Dan Fitzgerald to be a camp counselor alongside a couple of dozen other college hoops standouts across America, including Jason Terry (Arizona) and Shawn Marion (UNLV).

But this wasn’t a quick trip to Seattle or a straight shot to Los Angeles – he was asked to make the trek to Chicago, home of Michael Jordan’s Flight School.

Santangelo didn’t just jump at the opportunity, he leapt from the free-throw line.

“I don’t think you can understate the influence Jordan had on people born from 1975 to about 1985,” Santangelo said. “I still have the ticket stub from the 1991 NBA Finals against Portland. I was way up in the nosebleed section to see him.”

In Chicago, he was up close and personal.

Santangelo and the other college-aged counselors were essentially bodyguards for Jordan, helping clear a path between the youth players and fans and keeping the teens and their parents from surrounding him.

“Moms would literally reach through the tunnel we made to touch him,” Santangelo said.

At night in a tiny, old gym at Moody Bible Institute, Jordan and an assembly of NBA players including Juwan Howard and former Seattle SuperSonics draft pick Sherell Ford played the counselors in a series of pickup games.

Jordan’s crew often handled the five rotating college teams, including the squad that included Santangelo, who was admittedly nervous to be sharing the floor with His Airness.

When the butterflies subsided, Santangelo was able to score a driving layup past Jordan, who was matched up against another player on the near wing.

Jordan may have swiped toward Santangelo’s dribble, he said, but probably not enough to say he scored on arguably the game’s best player at the peak of his career.

“Watching him play up close, I was like a kid in a candy shop,” Santangelo said. “His first step took my breath away, it was so fast. And when he jumped – his head at the rim – he got into the air even faster.”

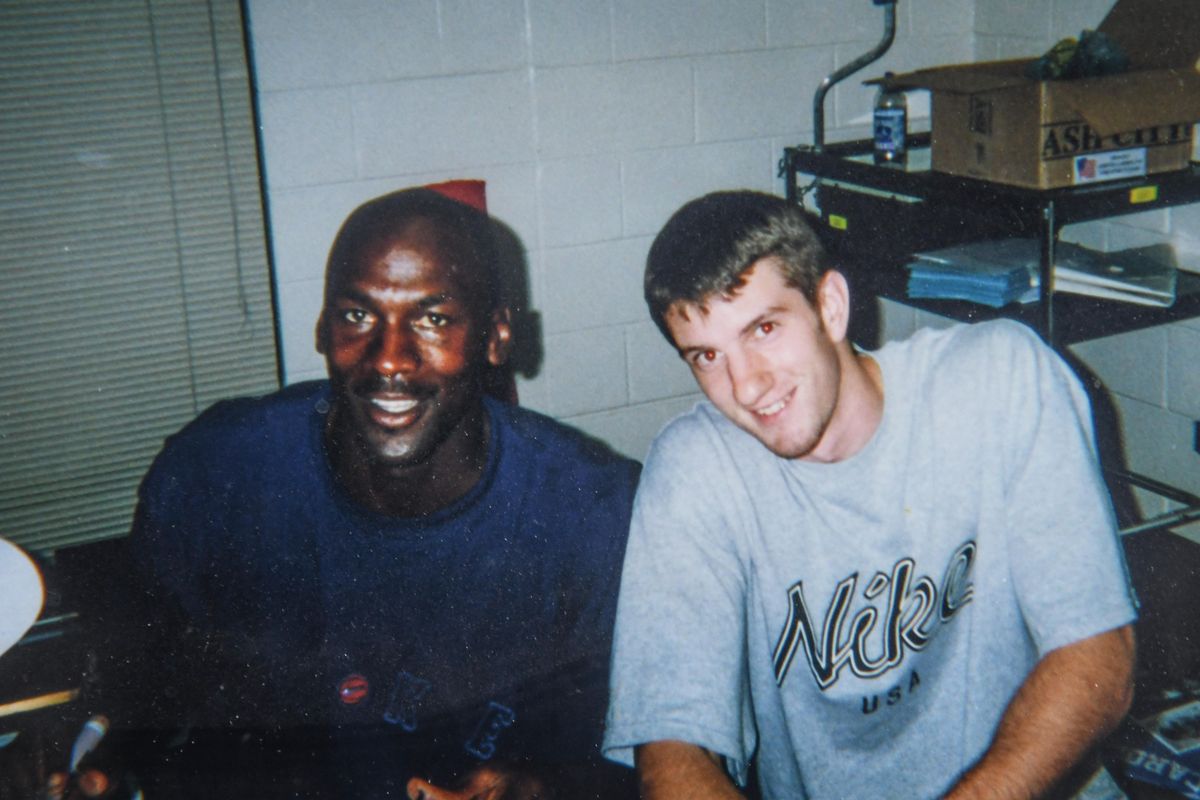

He left Chicago with a memento, too: a photo alongside Jordan that hangs in the dining room of his Spokane home.

He, his wife and three children all own Jordan brand shoes and have relished each episode of the “Last Dance” documentary.

“Meeting him was surreal,” he said.

‘Did you get the picture?’

Months after being drafted in the first round by the Atlanta Hawks, former Gonzaga point guard Dan Dickau’s 2002-03 rookie season coincided with Jordan’s short-lived comeback.

Jordan was 40 and devoid of his signature bounce as a member of the struggling Washington Wizards but still averaged 20 points, 6.1 rebounds, 3.8 assists, 1.5 steals and 37 minutes a game.

The floppy-haired, baby-faced Dickau averaged all of 10 minutes due to a knee injury.

Dickau still made it a point to face Jordan, someone he idolized since growing up near Portland and cheering for the Blazers, a team he distinctly remembers MJ dismantling in the 1992 NBA Finals.

Before the Hawks were set to tip off against the Wizards, Dickau caught up to his team’s photographer and made a request.

“I asked the photographer to be sure to get a picture of me alongside Jordan in the game, if we’re near each other,” Dickau said.

It soon happened when Jordan pushed the ball down the floor in transition, and a young Dickau picked him in the open floor.

“I remember understanding and realizing then and there the reality of guarding Jordan,” Dickau said. “And I guarantee I had a smile on my face.”

After that sequence and during a free throw, Dickau turned to the Hawks’ photographer.

“I asked, ‘Did you get the picture?’ which is something I would never do regularly in a game,” Dickau said. “It’s now in my office.”

The “Last Dance” series has evoked memories of that interaction for Dickau, a Spokane resident who has plenty of irons in the fire.

Dickau is a college basketball analyst, an owner of four barbershops, runs a basketball camp, contributes his basketball expertise to Scorebook Live and has used his time in quarantine to dive into the documentaries.

He went as far as re-enacting “The Shot” sequence on his Gonzaga-themed outdoor basketball court and posting the video to Twitter.

Dickau played the role of Jordan with a winning jumper over the outstretched of Spokane resident and former NBA forward Craig Ehlo, played by Dickau’s son.

“To be able to watch this, knowing these basketball stories and seeing how he did things … has been unbelievable,” Dickau said.

‘Everything he said, you just hung onto’

His family wasn’t wealthy, but Shantay Legans’ late mother, Susan, creatively budgeted to make sure her son got his favorite shoes.

Legans, who earned Big Sky Conference Coach of the Year distinction in March after leading Eastern Washington to a conference title, wore Jordans when he stood out on the Southern California prep basketball circuit.

He mimicked MJ’s look, from the shoes and arm band to the way he chewed his gum.

Bulls games were mandatory viewing for Legans, who also owned a life-size cardboard cutout of the 6-foot-6 figure.

The 14-year-old’s mouth dropped in 1996 when he was given a scholarship by the Santa Barbara Boys and Girls Club to attend a local Michael Jordan Flight School camp.

Jordan appeared godlike, Legans said, when he arrived on the campus of UC Santa Barbara to offer instruction to local youth players.

“Everything he said you just hung onto,” Legans said. “Just hearing him talk about his work ethic was special.”

The camp, littered with the children of Hollywood celebrities, featured some of the top high school players in the country.

“He played against them, and you would see what he would do to those good high school players, guys I thought were great,” Legans said. “He was so much better than them.”

Legans went on to become one of the state’s top point guards, ultimately starting three years at California before finishing his career at Fresno State.

Now married and a 38-year-old father of two, Legans has felt nostalgic since the first installments of “The Last Dance” were aired in April.

A framed photo alongside Jordan at the 1996 camp is among his most cherished possessions.

“(The documentary) brings you back when players in the league weren’t all buddy-buddy like they are now,” Legans said. “And you see how he pushed through all the hurdles, and the work it took to be great.”

‘MJ was everything basketball’

Former Kootenai High and Carroll College shooting guard Cassie Pimperton (nee Scheffelmaier) lives on a farm in north-central Montana nearly a decade removed from her last college game.

She’s now a 31-year-old wife, mother and head coach, recently leading Fort Benton to its third consecutive district girls basketball title.

It’s a life more busy and rural than when she grew up 30 miles southeast of Coeur d’Alene, but that hasn’t deterred her from diving into “The Last Dance” episodes.

Pimperton, who began playing competitive basketball before the WNBA’s inaugural 1997 season, idolized Jordan first.

“Before the WNBA grew, MJ was everything basketball,” she said. “I’d watch his games and then go outside and practice moves I’d see him do.

“I tried to include his fadeaway into my game.”

Wearing Jordan brand shoes, she had some Jordan-like scoring nights.

Wearing the No. 23, Pimperton led the North Star League in scoring before graduating in 2007 and taking her game to Umpqua Community College in Oregon.

At UCC, where Pimperton was also No. 23, she once scored 50 points in a 99-90 win over Clackamas, catching the attention of NAIA national tournament regular Carroll.

Pimperton ultimately signed with the Helena school, where No. 23 wasn’t available. She took the next best thing – 32 – instead.

She’s enjoying “The Last Dance” as a fan and coach as her young players are absorbing the content.

“It’s valuable for them to see that the best player on the team was first when it came to conditioning and pushing teammates,” Pimperton said. “It’s been fun for them to see his work ethic.

“They weren’t born in the MJ era, so this show has been fun for them to live it a little, too.”

‘He changed the game’

Eastern Washington guard Jacob Davison – the Eagles’ leading scorer and arguably the Big Sky Conference’s most electric dunker – wasn’t alive for peak Jordan.

Davison was born months before MJ secured his sixth and final title with the Bulls in 1998, the premise of the “The Last Dance” documentary.

He wore Jordan shoes in high school, viewed his highlights and has heard the endless “Jordan or LeBron” rhetoric, but Davison’s favorite player tag has been reserved for the late Kobe Bryant.

Growing up in the Los Angeles area, kids born in the 1990s often gravitated to the five-time champion Bryant, whose acrobatic dunks and killer-instinct was similar to Jordan’s.

Davison, who will return to EWU as a fifth-year senior, isn’t lost on who inspired Kobe.

“Kobe completely shaped his game after Jordan, that alone says something,” Davison said. “So he’s obviously one of the best – if not the best – players of all time.”

He’s learning more about Jordan with each episode of the ESPN docuseries.

One of the most creative, spring-heeled leapers in midmajor basketball, Davison thanks Jordan for helping significantly change the culture of the dunk.

“He changed the game,” Davison said.