Agriculture in a time of ash: Mount St. Helens eruption did little to stop momentum of record wheat year

Much of the 540 million tons of ash that spewed from Mount St. Helens during its eruption fell on ranchlands and crop fields across Central and Eastern Washington, creating a brief period of uncertainty for agriculture.

“It was a pretty big deal. People didn’t know what to do, and that included the farmers,” said Bill Schillinger, a professor and scientist at the Washington State University dryland research station in Lind.

In May 1980, Schillinger was just returning from a trip to Nepal to his family farm in Odessa. Schillinger said it was one of the hardest hit areas, with 4 or 5 inches of ash coating the fields, farm equipment and homes.

“I spent a lot of time that summer on the roof of my mom’s house, clearing it off,” Schillinger said.

Fears of a wheat harvest adversely affected by the volcanic ash were short-lived, however, as 1980 turned out to be a record year for the crop. Reports from the time show most agriculture in Eastern Washington and North Idaho was either largely unaffected by the cataclysmic eruption, or that larger market forces were at play in determining the financial success of crops and livestock.

While some areas, like Odessa, were blanketed with ash, the clouds didn’t cover all fields in the area to the same depth. The Palouse is also known for its deep, rich soil. A few inches of ash wasn’t enough to cause long-term effects on the soil, said Rich Koenig, chair of the Department of Crop and Soil Sciences at WSU.

“I am not sure the ash has had any long-term impact on agriculture, either positive or negative,” Koenig wrote in an email last month. “The amount of ash was variable, but still relatively small compared to the overall mass or volume of soil.”

Most farmers simply plowed the ash into the soil after harvest, said Randy Suess, a retired wheat farmer who was working for the schools in Steptoe in 1980.

“It was a Sunday afternoon when it erupted,” Suess said. “I came out of church, looked up and saw this big cloud. I thought, ‘I’ve got to mow the lawn real quick, it’s going to rain.’ ”

The ash fell just as the winter wheat had started to poke up out of the ground, which may have insulated the plants and killed off feeding insects, Suess said. Couple that with an above-average year of precipitation, and by the middle of the summer farmers were looking at a bumper crop.

“The wheat is so good and so thick in the low rainfall (nonirrigated) areas, you’d almost swear you could walk across it without touching the ground,” Scott Hanson, then-administrator of the Washington Wheat Commission, told The Spokesman-Review on July 20, 1980.

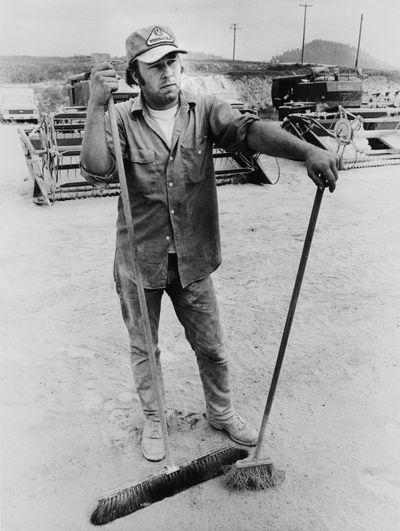

Getting the wheat out of the ground, however, proved a challenge. Suess spent his summer as a volunteer firefighter hosing down streets, sidewalks and the sides of buildings, as more and more ash would be kicked up when cars drove by. That ash would be sucked into the filters of trucks and combines plying the Palouse’s hills, leading to increased expenses in maintenance and parts.

“We’re seeing parts that should last two or three more years wearing out with just a few days’ use,” Mel Kagele, a wheat farmer near Ritzville, told The Spokane Daily Chronicle on Aug. 20, 1980.

And once it was out of the ground, there were fewer places to sell it, initially. President Jimmy Carter in January had ordered an embargo on wheat sales to Russia after the country invaded Afghanistan. In April, Carter ended diplomatic ties with Iran in the midst of the hostage crisis, cutting off the monthly sale of about 200,000 tons of Northwest wheat to the country.

By the end of August, wheat was being stockpiled at elevators as the ships carrying grain to the coast were overwhelmed by a record crop estimated at about 155 million bushels. By the end of the year, other countries had begun buying soft white wheat from the Northwest that were typically customers of the hard red variety grown elsewhere in the country. Scarcity of that variety caused Washington farmers to find new customers in Egypt, Morocco, Yugoslavia and Poland, according to a Dec. 28, 1980, agriculture report published in The Spokesman-Review.

Other crops that had faced uncertainty also experienced bumper years. The lentil crop in 1980 also set a record, and potato yields were higher than the year prior, although production acreage had fallen. That caused prices for a bag of potatoes to jump $1 in 1980.

Some cattle were lost as a result of ranchland ash damage, but for cattle ranchers, it was increasing interest rates that raised costs, according to that Dec. 28 report.