New book details history of contentious Cascade mine

Historians have a term for historical randomness: contingency.

It’s a simple idea. Things aren’t bound to happen. They aren’t preordained. Yet, decades after something has occurred, it’s easy to forget that.

Events take on a hue of inevitability.

Contingency is an underlying theme in Adam Sowards’ new book, “An Open Pit Visible from the Moon: The Wilderness Act and the Fight to Protect Miners Ridge and the Public Interest.”

Sowards, an environmental historian at the University of Idaho, digs deeply into the effort to block the mining of Miners Ridge in the Glacier Peak Wilderness Area. The fight, which started in 1966, defined key parts of the scope and breadth of the Wilderness Act.

“I didn’t realize, for example, that this was the first test of the mining provision for the Wilderness Act,” Sowards said.

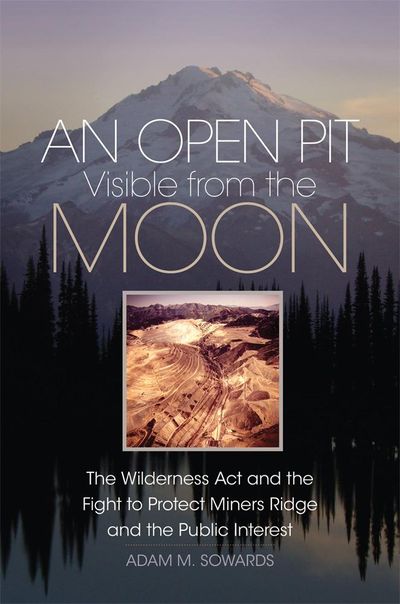

The act had been passed in 1964 and, until the Kennecott Copper Corp. proposed an open pit in the Cascades (which the opposition stated would be visible from the moon), a key provision allowing mining even in designated wilderness areas, had never been tested.

But when Kennecott announced plans to mine there, a diverse cast of characters resisted.

Those characters are what first drew Sowards to the story.

“I started the research and I found these wonderful stories with these terrific characters,” he said. “And I knew it was compelling.”

For instance, there was a Mount Vernon, Washington, doctor, Fred Darvill, who bought three shares of Kennecott simply so he could attend board meetings and protest the mine. The doctor went to a shareholders meeting in New York and presented an oil painting of the proposed mine area and said, “I’m here to speak to you about wilderness and beauty.”

“This is not how Kennecott stockholders tend to operate,” Sowards said.

Or the Ohio college student, Ben Shaine, who started a petition against the mine. The petition circulated among top U.S. scientists. Eventually, Shaine presented the petition to top executives at Kennecott. During a 45-minute meeting, Shaine realized that the executives were bothered by the popular resistance, but also tempted by the buried riches.

Which is another key finding in Sowards’ book. The fact that the mine was never built had more to do with the falling price of copper than with the grassroots resistance.

“It wasn’t the grassroots activism itself that stopped the mine,” he said. “It was a variety of things, but perhaps the biggest and most important thing was the changing economics of things.”

There are parallels, he said, to the current debate about coal.

That doesn’t mean activism was without a role. It’s just not the clear-cut, preordained one.

“If there hadn’t been so much agitation, I think the company could have gone ahead without having to be cautious,” he said. “And the fact that there was steady pressure for years around this meant that it was a harder thing for Kennecott to accomplish. If there is an analogy there, it is keep up the pressure.”

Plus, in the case of Miners Ridge, the opposition and awareness led to something else: the creation of North Cascades National Park. Although the ridge is not part of the park, Sowards found that the concern and energy generated by the fight for Miners Ridge led to creation of the park.

“People can be working on one thing and something else benefits,” he said.

And, even more important, the whole saga shows the importance of citizen involvement.

“This I think is the practice of citizenship,” Sowards said. “I worry today that we don’t do that very much.

“It was fascinating to me to watch people engage in this democratic process and try and define the future going forward in this particular place.”