Getting There: Rappelling engineers get close-up look at aging Latah Creek Bridge

Jeremy Miles, of HDR Engineering, left, and Zach Williams, of Fickett Structural Solutions, inspect the northwest side of the 140-foot-tall Latah Creek Bridge for deterioration on March 11, 2020 in Spokane. Miles says he feels safer hanging on the rope than climbing a ladder. (Dan Pelle / The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

Jeremy Miles spends most days behind a desk at HDR Engineering in Spokane. But he spent a recent Wednesday suspended midair off the side of the Latah Creek Bridge.

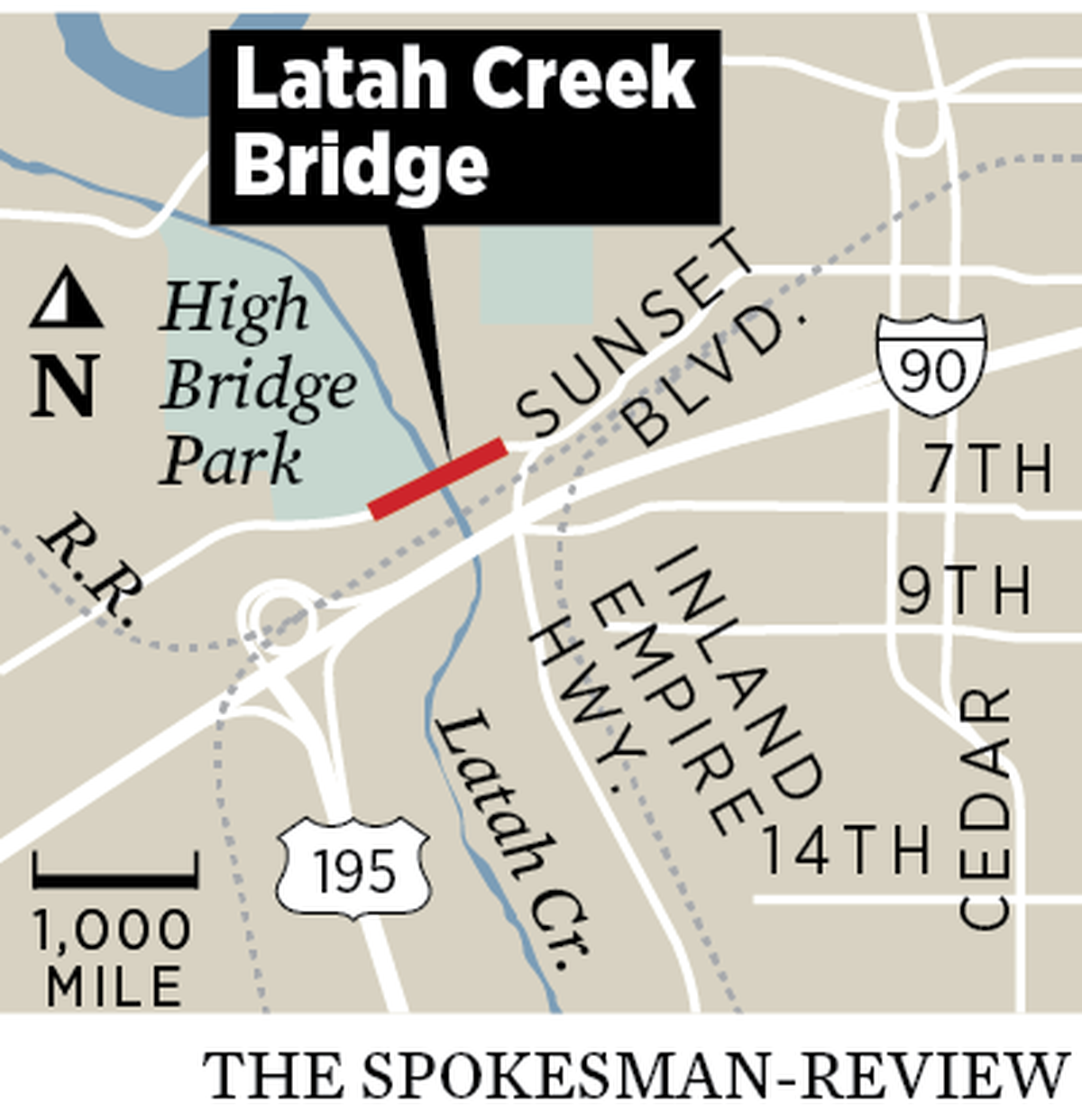

Miles was there in the air, between the deck of the 109-year-old, 140-foot-tall span and Latah Creek, as part of a biennial inspection process mandated by the Federal Highway Administration and overseen by the city of Spokane.

While the city was able to do much of the inspection itself, it brought in two engineering firms – HDR Engineering and Fickett Structural Solutions – to access areas the city couldn’t reach without the aid of crews trained and certified by the Society of Professional Rope Access Technicians in what Miles called “industrial rope access.”

What they found, Miles said, wasn’t much.

“All in all, considering its age, it’s in decent shape,” Miles said once he was safely back behind his desk. “Obviously there’s minor issues.”

There’s also one major issue with the bridge, though the city has known about it for years.

The problem is that the bridge’s deck has deteriorated, prompting the city to reduce traffic from four lanes to two and close the bridge’s sidewalks several years ago.

The decommissioning of the outdoor edges of the bridge also means the city isn’t able to employ its standard procedure for inspecting under bridges. That procedure involves the use of an under-bridge inspection truck. UBIT trucks, as they are commonly known, have an arm that resembles the arm of a cherry picker, except it reaches down instead of up, allowing crews to inspect the structure of a span up close.

The middle of the bridge, which was designed for ultraheavy trolley cars, is “really robust,” Miles said, but a UBIT truck wouldn’t be able to reach to the bridge’s edge, and then underneath it, without parking in the lanes that have been taken out of service.

Hence, Miles and his fellow rappelling inspectors. Hence, also, a drone buzzing around them.

Clint Harris, director of the city’s streets department, said the drone was deployed to do its own inspection of the bridge.

Once the drone’s inspection report is produced, Harris’ department will “correlate that” with the one Miles and the other humans conducted, ensuring the drones were finding the same issues or noticing the same information that the climbers found visually.

“We don’t have any results from it yet, so we can’t say it was a great success or it was not a success,” Harris said. “So we’re looking forward to getting that information back at some time.”

Harris said the city “wouldn’t switch over to the drone model exclusively,” even if it proves reliable. The hope instead, he said, is to reduce how often people are asked to engage in what he called the “risky” job of rappelling over the side of a bridge.

The city maintains 66 bridges, not all of which are in as good condition as even the partially decommissioned Latah Creek Bridge. The Post Street Bridge near Spokane City Hall was closed to cars last year, after a structural analysis deemed the 102-year-old span was unsafe.

Work to replace the 333-foot bridge deck, but retain its arches, was supposed to start last year. But when bids came in over budget, the $21 million project was delayed. The city expects work to begin in April and continue to at least winter 2022.

The city also plans this year to replace the deck of the Hatch Road Bridge, located just south of Spokane off U.S. 195, Harris said.

The list of bridges in need of work is long – and not limited to those overseen by the city.

The Washington State Department of Transportation has a long list of spans in the state and in its Eastern Region that need work.

It won’t be cheap. DeWayne Wilson, bridge asset management engineer for the department, estimates the cost to preserve these bridges will be about $116 million over the next 10 years. That includes the $23 million the Department of Transportation plans to spend to replace the East Trent Bridge in Spokane.

Built one year before the Latah Creek Bridge, in 1910, the East Trent Bridge was an improvement on its predecessor, a wooden structure resting on wooden pilings. But in April that “new” structure will be demolished and rebuilt with a shared-use path on one side, a sidewalk and bike lane on the other, and two lanes of traffic in between.

The state’s team of bridge inspectors – which includes its own in-house diving team that can examine underwater bridge elements down to 100 feet – examines each span every year or two and rates them as being in good, fair or poor condition, Wilson said.

Overall, the state’s bridges are in fair condition, though about 10% are in the poor category. And Wilson said “things are going to get worse” without interventions.

Spokane has 11 bridges in the poor category. Wilson said many of the area issues are a result of studded tires, which tend to rut the surfaces more than elsewhere in Washington.

WSDOT crews will begin work on one bridge-deck project Monday, when they start the job of forming a new bridge deck on state Route 902, directly over Interstate 90.

The project, part of a larger revamping of the interchange, will require the overnight closure of first the westbound lanes through April 1, then the eastbound lanes of I-90 through April 10.

During the closures, drivers will be detoured off I-90 using the off-ramps at the SR 902/Medical Lake interchange, routed through the intersection with SR 902 and sent back onto I-90 using the on-ramps.

But some of the issues are more complex than a deteriorating surface.

Inspectors have detected movement in the piers of the two Interstate 90 bridges over Latah Creek. Wilson said the Department of Transportation is working to monitor the movement and “come up with some kind of a plan to stop the movement.”

He said the issue doesn’t make the spans unsafe, which will give WSDOT time to “bounce around ideas about possible fixes” and scope the costs of those options.

The Department of Transportation hopes to settle on a fix in the next year or so. As for actually implementing a fix, that’s less clear.

“When it gets funded is kind of undecided right now,” Wilson said.

And funding is an underlying concern all around for WSDOT as it looks to its aging infrastructure.

“When we’re looking at the next 10 years and based on the funding levels that we have, we’re probably running about 30% of what we need,” Wilson said.

“So that becomes a challenge: How do you use that 30% to address the issues?”

That will leave the department to make “some hard choices” over the next five to 10 years.

“And we’re not going to be able to fix everything,” he said.