What do we really know about this little bug that’s turned our lives upside-down? Quite a bit, actually.

What is a coronavirus?

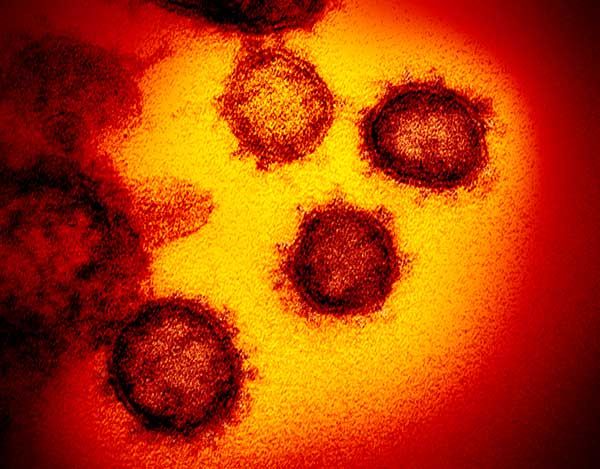

First off, let’s clarify our terms. We’ve all been calling this thing the coronavirus, but acutally, coronavirus is a type of virus. It’s called that because the little spiky things protruding from the virus reminded researchers of a crown. “Corona” is Latin for crown, or halo.

You may remember SARS (Severe acute respiratory syndrome) from 2003 and MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome) from 2012. Both of those were caused by coronaviruses.

For a while, folks were calling this one “the novel coronavirus,” meaning it was new. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention prefer the name COVID-19 for the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2.

Coronoviruses affect only birds and mammals.

NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF ALLERGY AND INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Where did it come from?

The short answer: Researchers don’t know just yet.

Early research in the U.K. suggested the COVID-19 virus is similar to one found in horseshoe bats. That’s not so far-fetched as its sounds: SARS spread from bats to cats to humans. And MERS originated in bats and spread to camels before the first human was infected.

The first human cases of Covid-19 were detected in early December in the Wuhan Province of China. The CDC says the first cases of COVID-19 were linked to a live animal market there. The Chinese government has said they now think the very first case may have been a 55-year-old man who fell ill on Nov. 17 of last year.

From there, Covid-19 spread around the world.

CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL

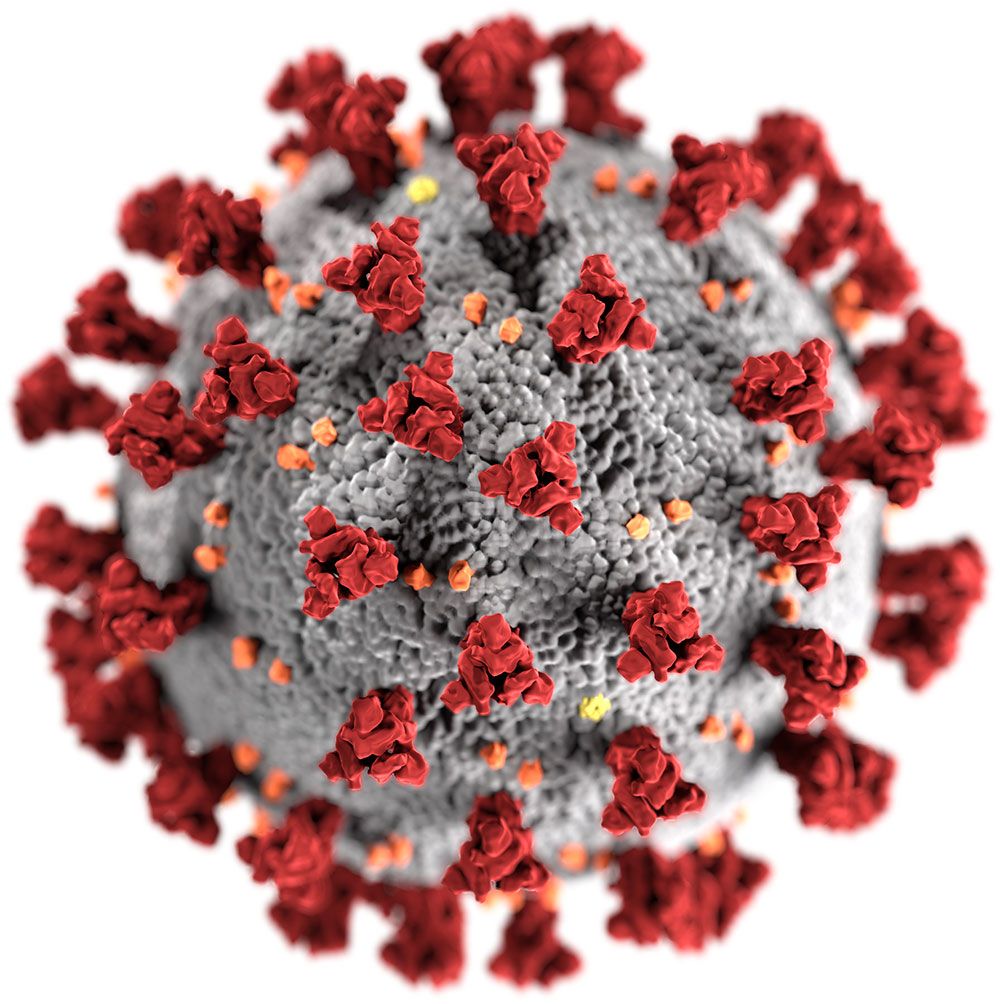

How does the virus work?

Like all viruses, this one has just one purpose in life: to reproduce. This only becomes a problem when the human body detects the virus and then goes into overdrive to try to rid itself of the virus. Most of the respiratory symptoms a patient suffers are actually brought on by the body’s immune system.

Once it’s in the lungs, the virus uses prtrusions made of spike proteins to latch onto a receptor on a lung cell. Researchers have noted that the COVID-19 virus seems to be “stickier” than, say, the SARS virus. Which may be one reason this strain has spread more quickly.

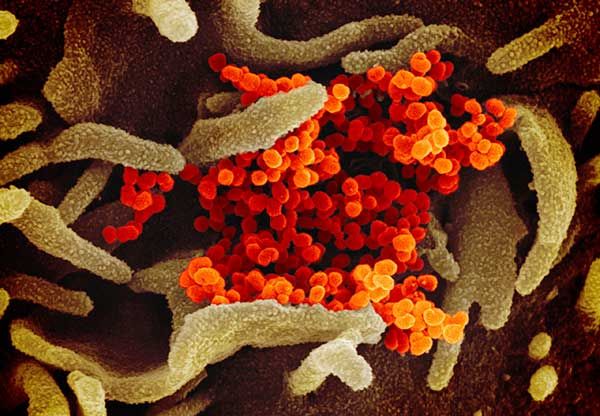

NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF ALLERGY AND INFECTIOUS DISEASES

The virus then tranfers its RNA into the lung cell and highjacks the cells reproduction machinery. Copies of the virus emerge from the host cells and then go out in search of new host cells where they repeat the process.

This electron microscope image shows COVID-19 viruses as they emerge from the surface of host cells in a lab culture taken in February from a patient in the U.S.

How does the virus spread?

COVID-19 can damage the lungs. But how does the coronavirus gain access to the lungs?

For the most part, COVID-19 spreads from person-to-person. An infected person can cough or sneeze, spreading the virus through tiny droplets that are too small to see.

COVID-19 can also live for a period of time outside the body. So these drops can come to rest on a table or counter that can be touched by someone else who comes along later.

This is why we’ve been advised to not touch our mouths, noses, and faces. Cells in our mouth and nasal tissues also have receptors for the spike protien. We can get droplets on our fingers that we then multiply and spread to our own respiratory systems.

Numbers based on 03/18/2020 12pm counts