Scaring cougars for science: Research in northeast Washington looks at effectiveness, long term impacts of hazing

She’s not that big, at least by big-cat standards, but even 35 feet up a tree surrounded by five baying hounds, she looks unconcerned.

Standing beneath her on a sunny Tuesday in February, it’s hard not to draw comparisons between this 80-pound cougar’s lethargic disinterest and my 9-pound housecat’s lazy indifference, although her teeth – visible the two times she hisses – remind me of the scale of things.

I’m tagging along on a Kalispell Tribe research project run by wildlife biologist Bart George and a handful of volunteers.

The goal is to test the effectiveness of various ways of scaring cougars while also documenting whether these methods prompt mountain lions to change their behavior.

The cat’s seemingly cool demeanor is an early, and incomplete, indication of success. One week ago, when she was treed by dogs, she was “snarling,” said Bruce Duncan, an experienced houndsman who has treed more than 1,000 cougars and is a volunteer for the tribe and WDFW.

“Super calm,” he said, speaking loudly to be heard above the din of dogs. “She’s like, ‘I’m all right.’ ”

Now, a week later, her behavior has changed, indicating that she’s changing her behavior in response to the hazing, an outcome George said is positive.

In 2019, George helped the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife kill 68 cougars For the most part, these were cats that attacked, killed or threatened livestock or pets.

That increase in lethal removal follows a spike in cougar sightings, particularly in Northeast Washington. For George, and the Kalispel Tribe, that’s a concern both for livestock safety reasons and from a wildlife management standpoint.

“That’s 70 cats that got killed that are not available to licensed hunters,” George said. “And they’re not being used. Which is really a shame. They go in the dump. Whether you’re for or against trophy hunting, at least when that cat is being killed by a hunter, it’s being utilized.”

George assisted WDFW on many of these depredation calls and noticed that despite the yapping of dogs and the babble of humans, the cats often stayed within 200 yards.

“That cat ought to be afraid of human voices and dogs barking,” he said. “We’re not sneaking around out there. We’re making a ton of noise … they ought to be moving away.”

George designed a study that he hopes will give WDFW another management tool, while also shedding light on the behavior of a notoriously secretive animal.

“I just want it to be useful information. Not just research for the sake of research,” he said. “Ultimately, it could help save cougars and save heartache for people losing pets and livestock.”

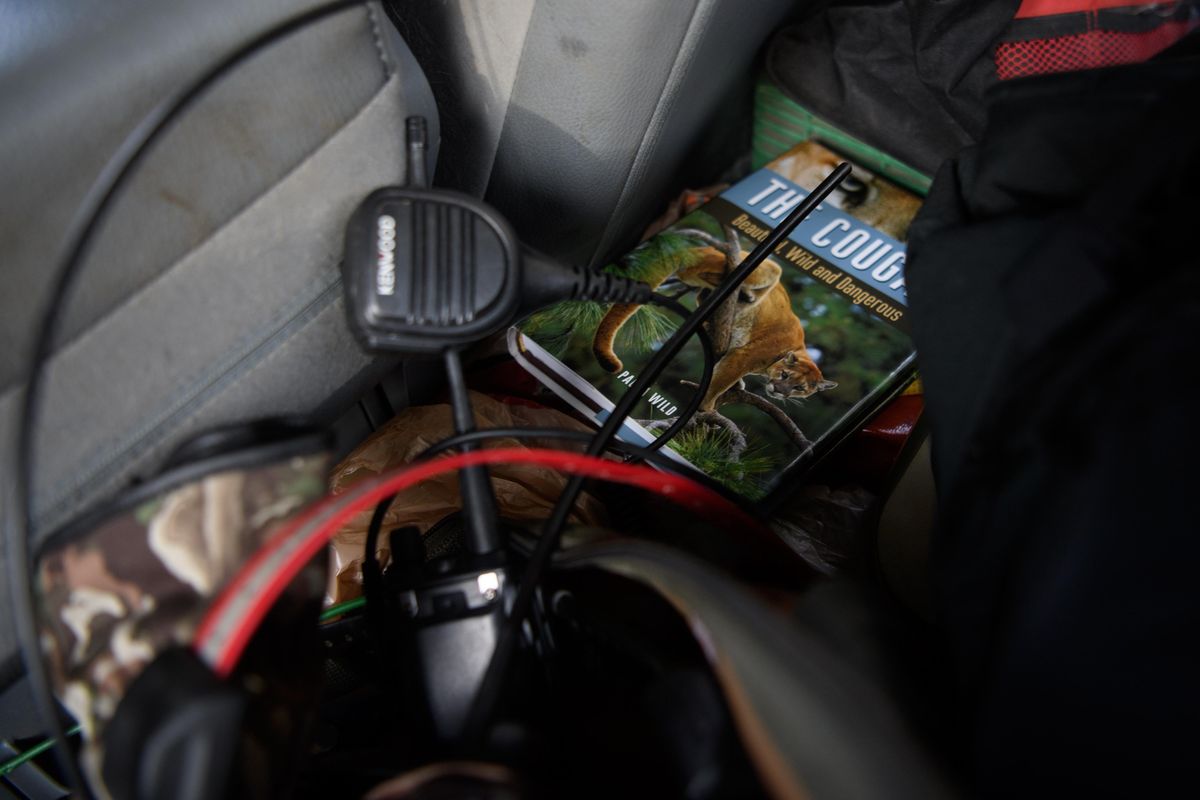

Bart George, a biologist with the Kalispel Tribe smiles at his hound Whisper as she watches him from the cab of his truck while researching mountain lions on Tuesday, Feb. 25, 2020, near Colville, Wash. George uses GPS collars to track mountain lions and see how they respond to pressure from humans and dogs. (Tyler Tjomsland / The Spokesman-Review)Buy a print of this photo

‘Throwing snowballs’

The 80-pound female was first reported by a man in Northeast Washington, saying he’d “seen a cougar.”

George was not impressed.

“We get a lot of calls like that,” George said.

So he asked, “What does it look like?”

“It looks like a freaking cougar,” the man responded. “It’s just sitting here looking at me.”

“He’s looking at you right now?” George asked.

“Yeah, I’m throwing snowballs at it,” the man said.

That’s not normal behavior for an animal known for stalking its prey, silently, for hours. But the mountain lion also hadn’t attacked any livestock or pets, making it a perfect candidate for George’s study.

George drove to the man’s house, tracked and treed the animal and outfitted her with two collars. One collar tracks the cougar over the course of days and weeks. The other, a Garmin GPS device, gives instantaneous real-time information when turned on.

His hypothesis is that cougars won’t run simply from human voices. Instead, they need to associate humans with a strong negative interaction.

To test this, George walks toward the cat playing music or a podcast at 80 decibels. Once the cat starts to flee, he stops and marks the distance. He then releases dogs and trees the cat.

Throughout, George records what kind of terrain the animals flees through, which gives him a rough sense of how much energy it’s expending. If the cat heads sharply uphill, or through thicker brush, it’s expending more energy, thus indicating a greater level of avoidance.

Once the animal is treed, George and his team of volunteers and dogs leave. They repeat this same hazing ritual for each collared cat at least three times.

George collared several other cats and is not hazing them so he can compare and contrast any changes in behavior.

“The idea is that we would see those distances expand over the course of the project,” he said.

The study design is based off bird flight initiation distance projects, but this kind of data hasn’t been gathered for cougars.

“How would you?” he asked rhetorically. “For one, they’re secretive. The technologies never really existed to have that real-time data, and even now it barely exists. We’re just kind of piecing it together.”

Starting from the bottom

The study of ecology, as its practiced today, is a relatively new discipline which only really “ramped up” in the 1950s after “a time of really intense marine and terrestrial harvest,” said Aaron Wirsing, an ecologist at the University of Washington who studies sharks and wolves. Because of that, much of our understanding of how animals live and behave, particularly predators, is “stunted,” relying on faulty (or just plain wrong) baseline assumptions.

“Much of what we know about predators is based on science (from) after we suppressed predator numbers globally,” he said.

It wasn’t much different for cougars, although unlike wolves and grizzlies, they were never fully extirpated from the West. Still, those that survived were secretive animals made more wary by intense human hunting. This made studying them hard, if not impossible.

This point was driven home when we headed up into the woods near Chewelah, Washington.

According to the Garmin, the 80-pound female cougar was several hundred yards from us, across a creek and up a hill. George and Duncan barreled through the underbrush, leaped a stream and raced uphill. All the while, Steve Rinella, a hunter and writer who hosts the popular podcast “Meat Eater,” droned on in his distinctive Michigan drawl at 80 decibels.

Finally, after 20 minutes of hiking, George stops. The cat had started to move. We were 202 yards away. Without the magic of modern technology, we’d have never known a cougar was nearby, much less when it started to flee the sound of Rinella.

We were able to watch as the animal fled for 500 yards and then stopped. George released his hounds.

On a follow-up hazing, roughly a week later, the cougar fled for 900 yards, which indicates to George that the adverse conditioning is working.

“They’re making that association between the human voices and that negative interaction,” he said.

Conflicting theories

In Washington and other western states, cougar sightings and encounters have risen dramatically in the past years. Biologists and wildlife managers disagree on why.

Some, including George, believe the increase indicates, among other things, a growing cougar population. Others say that’s not necessarily the case, arguing instead that an expanding human population, combined with greater awareness (driven in part by breathless media coverage), is leading to the surge. According to one WDFW study, the rate at which cougars enter and inhabit human areas remains relatively steady, regardless of the overall cougar population. That finding comes from a study in western Washington, near Snoqualmie.

That fundamental disagreement underscores just how little we know.

“Every time I review a paper for publication and they start using the word ‘behavior,’ I tell them they can’t use (that word) because they don’t have the data,” said Mat Alldredge, a Colorado Parks and Wildlife biologist.

Alldredge has also studied cougar hazing and he’s skeptical that it has any long-lasting impact.

In 2019, he published a paper in Ecology and Evolution examining human and cougar interactions in Colorado’s front range. As part of that, he looked at what types of adverse conditioning (hazing) led to lasting behavioral changes.

“My general conclusion is that no matter what we tried, we instilled the fear of humans in lions, which is a good thing,” he said. “But it isn’t necessarily changing behaviors.”

Alldredge’s research didn’t look at the impact of hounds.

He believes it’s “next to impossible” to get cougars to associate a negative human interaction with an undesirable behavior. That’s because, Alldredge said, researchers and wildlife managers are playing catch-up, responding to cougar depredations after the cats have received their reward.

“It’s pretty easy to sit by a dumpster and do something to a bear when it touches a dumpster,” he said, as way of example. “How do you do that to a lion?”

Alldredge said in his Colorado study, more than 80% of the lions entered urban or suburban areas between 10 p.m. and 5 a.m., a time when most humans are not out and about.

Instead, he believes the issue is a thornier, more complex one. As humans expand into formerly wild spaces, we’re bound to run into the animals that also live there.

In Colorado, as in Washington, neighborhoods with green lawns and leafy bushes attract deer and other prey, which in turn attract cougars.

“It’s good to continue to instill that fear of humans in lions, but lions are utilizing these urban areas for food resources because they’re consistent,” he said. “I like to say the grocery store is always stocked.”

Another tool

Regardless of what George’s study finds, it will shed new light on cougar behavior. That’s information managers and the public need.

Mike Sprecher, a WDFW enforcement officer who covers Spokane and Lincoln counties, said he hopes George’s research will give him a tool to “modify” cougar behavior.

“We may save more cougars in the end,” he said.

Public interest in the project was evident.

After treeing the cat, we leashed the dogs and headed back to the trucks. It was 11 a.m. An easy day, the men agreed. The cougar didn’t run too far and the terrain wasn’t too steep. They loaded the dogs – the canines’ yapping and yowling calmed somewhat by the hunt – and drove into town to get a lunch.

At the Subway in Chewelah, we ate and chatted while George logged data from the day.

George is the only one in a uniform (a FirstLite shirt with a Kalispell Tribal logo patch on the chest). It’s clear the group has been working in the woods. As we leave, two older women ask what we’ve been up to.

One of the volunteers explains, in broad terms, the project.

“Oh, thank you,” one lady responds. “Thank you. We need that up here.”