This column reflects the opinion of the writer. Learn about the differences between a news story and an opinion column.

Shawn Vestal: Let’s keep the region’s history in the region – on the very land where it occurred

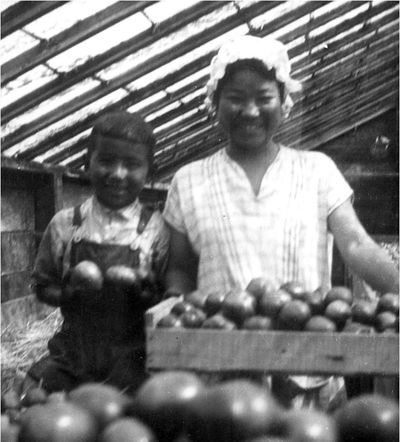

Around a century ago, the Uyeji family came to America from Japan, settling in a neighborhood on the outskirts of Seattle known as Pontiac.

They lived there and farmed the land, in an area now known as Hawthorne Hills, along with their Japanese-American neighbors. In 1942, when the U.S. government ordered all Japanese-Americans within certain areas along the coasts, known as “exclusion zones,” to be moved to camps in the country’s interior, the Uyejis were taken to first one, then another internment camp in California, according to Discover Nikkei, a website that tracks the histories of Japanese immigrants to America.

They were interned for two years. When they returned, the Uyejis found their land had been sold and then condemned by the government for Navy use. Tomiko Uyeji returned to find what she called “cement and a monstrous thing for a warehouse,” Discover Nikkei says.

The warehouse was later turned into the National Archives at Seattle in 1963, and it has remained so ever since. In other words, in an ironic reflection of this dark history, if you want to examine the history of the Uyeji family to this day, you go to an archive on the very land the U.S. government took from them.

The archives still have the key to the front door of the family’s former home, for heaven’s sake.

That deep, if troubling, history is one of several reasons that Washington Attorney General Bob Ferguson is threatening to sue the Trump administration over its rash plan to shutter the national archives at Seattle and ship millions of regional records to Kansas City or California – including internment-camp history and tribal records for more than 270 tribes in the region.

This is about more than where the boxes are warehoused – much more. If these records are sent off to Kansas City, they may as well be shredded, in terms of public access. We need to keep these records, and we need to keep them there, close to the people and places for whom this history is personal.

“Shipping these records to Riverside or Kansas City will effectively eliminate public access to the records,” Ferguson wrote in a letter to federal Office of Management and Budget, “creating insurmountable obstacles for local tribal members and other affected communities in the Pacific Northwest seeking access to critical historical resources.”

‘The past isn’t gone’

When Laurie Arnold, an associate professor of history and director of the Native Studies program at Gonzaga University, was researching tribal records at the National Archives in Seattle, she came across a pronounced historical echo.

She found documents from the early 1900s showing that federal officials were taking notice of the fact that Native people were “complaining” about smelter pollution from Canada flowing down into Washington’s waterways. Today, about a century later, the tribe remains locked in a legal battle with Teck Resources Ltd. over lead and zinc mining pollution in the upper Columbia River.

“All of these resonances really reinforce the continuity of the conversations that happen in our region,” Arnold said. “It reinforces the presence of Native people in the region, and illustrates that the past isn’t gone.”

Arnold is the author of “Bartering with the Bones of Their Dead: The Colville Confederated Tribes and Termination,” which was published by the University of Washington Press in 2012. She is an enrolled member of the Sinixt band of the Colville Confederated Tribes. Her next project is an examination of the history of Indian gaming.

For her, it is important that the region’s historical documents be physically kept in the region. She sometimes takes students to study archival material, generally, and said there is a fundamentally different reaction to examining original records over digitized content. She described her own reaction to the materials at the Seattle archives as amazement.

“The documents need to stay in our region, because they are about our collective households, our neighbors, our families, our communities,” she said.

Ferguson, who has challenged the Trump administration frequently, is making that very case to the Office of Management and Budget, which announced it planned to sell the archives center and move the documents to another warehouse.

Among the records of regional interest, he cites the fact of a “significant body of tribal and treaty records” related to 272 federally recognized tribes in Alaska, Washington, Oregon and Idaho.

Ancestral history

In addition to tribal histories and records related to the internment of Japanese-Americans, the Seattle archives contain 50,000 case files relating to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, another important, if uncomfortable, chapter in the history of the Pacific Northwest.

That law blocked most Chinese laborers from coming to America, and required extensive and cumbersome application processes for those few who could try to enter or re-enter after having gone home to China. It also denied Chinese immigrants a pathway to citizenship. It was the first act that targeted a specific racial or ethnic group; it was repealed in 1942.

The archives contain records of the individuals who applied to enter the country at ports in the Seattle area, and they include photographs, biographical information, notes from interrogations, personal letters and documents, and other records, according to Ferguson’s letter to OMB.

For Chinese-Americans in this region, it can be an invaluable resource for doing genealogy work. The archives staff has been bolstered by a team of volunteers who are working to index those files for such use.

“But removing these files from the Pacific Northwest would end this work and make local access to these critical historical files impossible,” Ferguson wrote.

Ferguson is challenging the decision on a variety of legal grounds. He argues that OMB did not follow the law in preparing standards and criteria for a potential sale, and that the decision illustrated “a complete failure” to follow standards for such a sale set out by Congress.

He has threatened to sue if the feds don’t reconsider.

If it ends up in court, the archives could not have a better defender than Ferguson’s office. The attorney general has filed more than 50 lawsuits against Trump administration excesses and overreach; he’s won several times, and hasn’t lost once.

When the National Archives announced the planned sale and closure in January, they emphasized that some digital records would be available, that people can request copies of the documents by mail and that the records would still be available for in-person inspection – though hundreds of miles farther away.

All of which truly misses the point. If the archives are to be of true use to those of us whose histories are tied to this region – of true use to researchers and genealogists, to students and teachers, to tribal members and descendants of interned Japanese-Americans – then they need to be available here, now, physically.

On the same ground where the history occurred.