Questions of bias raised by Pullman police arrest of Black man using pepper spray in February 2019

Body cameras captured a Black Washington State University student facedown on the blacktop in February 2019. David Bingham called for a police officer’s help moments after he’d been pepper-sprayed, shocked with a Taser and handcuffed.

Sometimes police only get seconds to think, Pullman Police Chief Gary Jenkins said.

In this case, two and half seconds passed between Officer Alex Gordon yelling “Stop, police!” and pepper spray being fired into Bingham’s eyes.

Gordon had arrived outside a Pullman bar to find the 21-year-old Bingham in a fistfight with another Black WSU student, George Harris. As Gordon approached, he said the fight appeared to be mutual, making it legal under state law, but in violation of city code.

Bingham punched Harris from on top. Gordon pepper-sprayed Bingham’s face, missing Harris. Harris punched Bingham as he stepped back, pepper-sprayed. Eyes squeezed shut, Bingham said, he slammed Harris to the ground and Gordon shot his Taser into Bingham’s side.

Harris, unharmed by police, walked away with a warning for violating the city’s fighting code. Bingham was arrested for fourth-degree assault and obstructing law enforcement, both misdemeanor charges the prosecutor dropped days after the body cam footage was released, Bingham said.

“If he got force used on him, he should probably be under arrest for something,” Officer Wade Winegardner said in body cam footage, moments after placing a third Black WSU student in a chokehold.

That student, Damani Thomas, would be arrested for obstruction after filming police with his cellphone and refusing to back away.

The Fourth Amendment bans unreasonable seizures, which include police use of excessive force. The Supreme Court decision Graham v. Connor defines reasonable force with three criteria: severity of the crime, whether the suspect poses an immediate threat, and whether the suspect is resisting arrest.

In this case, Harris told police he wanted to see Bingham prosecuted. Gordon argued against arresting Harris. Officers at the scene argued, “If we’re using force on people, then we need to do a criminal charge,” as an out-of-view officer said in the video. Once they determined Harris had not been hit by the pepper spray, they agreed to let him go.

“When we have to use force to protect people, even if people say everything is good and we let everybody walk away, someone later on talks to friends who are law students. They get advice from people saying, ‘Hey, if officers used force on you, you need to file a complaint. If you didn’t get arrested, they shouldn’t have used force,’ ” Jenkins said. “It makes it really complicated.”

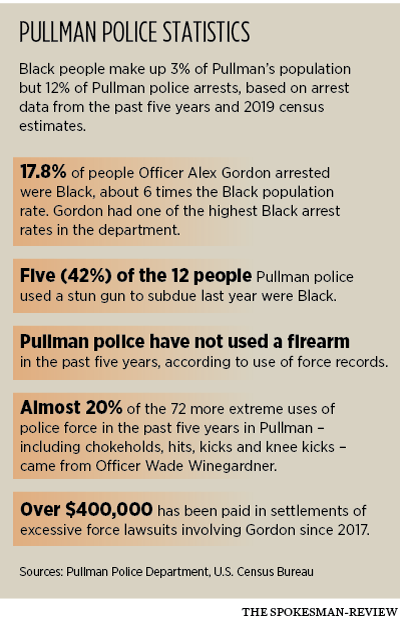

Since 2017, Pullman PD has paid more than $400,000 in settlements of excessive force lawsuits involving Gordon, including a suit over using a Taser and injuring Black WSU student Treshon Broughton, according to settlement records released by the police department.

Until Bingham watched the body cam footage, he didn’t think his injuries influenced his charges. But from the start, he believed his race played a part in Gordon’s quick decision to use pepper spray and a Taser, and, in Bingham’s view, Harris was simply lucky to miss Gordon’s line of fire.

Pullman police arrest Black people and use force on Black suspects at four times the city’s Black population rate, based on arrest data from the past five years and 2019 census estimates.

Gordon had one of the highest Black arrest rates in the department – 17.8% of people he arrested were Black, about six times the Black population rate.

While Pullman police have only used Tasers on 12 people in the past five years, five of them were Black.

Jenkins said he was happy when WSU criminal justice researcher David Makin found no evidence that Pullman police were more likely to use force, or to use it faster, with minority suspects. Makin’s results, based on an analysis of body camera footage, have not yet been published.

Jenkins said Pullman PD’s excessive force settlements are determined by the department’s insurance providers, who take into account what they think a jury would find.

“I don’t think they did anything unlawful,” Jenkins said, referring to the Broughton case. “I don’t think they used excessive force. I do think it looked horrible. … It looks horrible to the public.”

But he couldn’t point fingers at Gordon or the other officers involved. Though the lawsuit alleged excessive force, false reports and malicious prosecution, the officers’ conduct was within policy and training, Jenkins said.

Nine months after the incident involving Bingham, Jenkins said the department underwent new training from a use-of-force expert because the chief wasn’t happy with what he’d been seeing.

Arrest rates of Black people remained at about 12% in 2019, consistent with previous years.

“I can’t blame the officer for any actions that might not look good, or someone else might think is excessive, if he was doing everything the way we trained him,” Jenkins said.

Bingham said the impacts of police force go beyond what a jury might see through the lens of a body cam.

Removing the Taser barbs from his side cost Bingham $2,000 in hospital bills, which he said the department refused to pay for. Jenkins said if police injure an uninsured suspect, Pullman Regional Hospital will usually write off their medical expenses. Bingham said someone in the police department told him to file for a loan.

Bingham also photographed dozens of abrasions on his torso and wounds on his rib cage where the barbs had been lodged. But the marks aren’t what stuck with him.

“It was really traumatizing. It did a lot to me mentally,” Bingham said. “Bruises and scars can be healed, but when you have people in power look at you like you’re the problem and they don’t even give you a chance, it makes you realize there’s a lot of change that needs to happen with police.”

Police who arrived later made a bad situation worse, Bingham said. Gordon was the only officer who’d seen the fight, but a group of police who arrived after the action huddled up to decide Bingham’s fate.

“As I was sitting there I could hear the officers, and they didn’t even know the real name of the person I got in the altercation with,” Bingham said. “From then on, I just knew it wasn’t going to be good for me.”

The department keeps careful track of uses of force. Supervisors review every situation to check for patterns, Jenkins said.

The department uses a numeric system to flag police for review. Whenever an officer uses force, receives a complaint or causes a traffic collision, he or she will get a point. If an officer accumulates three points in a 12-month period, that leads to a review.

In the past 12 months, Gordon and Winegardner both have amassed eight points for uses of force.

In Bingham’s case, using a Taser made sense to Jenkins.

“I think if you’re the person that’s being victimized at the time, you want the officer to use whatever is the most effective and expedient method to have that assault stopped,” Jenkins said. “If we were sued, I think our best witness would be Mr. Harris, who was at the wrong end of Mr. Bingham’s fist.”

Harris declined to be interviewed for this story.

Bingham told Gordon at the scene that he was defending himself. He claimed Harris started the fight. When Gordon pepper-sprayed Bingham, Harris took the opportunity to get punches in, according to Bingham’s account.

Police interference in the fight left him blinded and vulnerable, and he felt sure that police would not protect him, Bingham said. Slamming Harris to the ground seemed to be his only option.

“It was either protect myself or get hurt,” Bingham said in the police car. “I just didn’t want to get hurt. So when you shot me, the only thing in my mind was, as soon as I go down he’s gonna start stomping me out.”

In that situation, Bingham told Gordon that police couldn’t protect him.

Low trust of police officers results in more police uses of force, Jenkins said, and lack of trust is one of several factors that could lead to disproportionate arrest rates of Black men. He said Black suspects seem to resist arrest more often, and he can understand why.

“Where that person comes from makes a big difference in how they interact with officers,” Jenkins said. “People from rural communities seem to have a better experience than those that come from an inner city. (People from cities) are expecting police not to have respect for them or to harass them.”

In the case last February, Thomas, the Black student who recorded the struggle with police on his phone, begged Officer Winegardner not to shoot him as Winegardner tightened the handcuffs.

“Please don’t kill me. Please don’t shoot me. Please, I’ve had cops put a gun to my head,” Thomas said.

The since-graduated criminal justice major and Vice President of WSU’s Black Men Making a Difference (BMMAD) had been filming with his phone as Winegardner cuffed Bingham. Police told Thomas to back up. He didn’t, and Winegardner put him in a chokehold before arresting him for obstruction.

“I have a right to record, you have no right to (expletive) arrest me,” Thomas said.

Dashcam video recorded Thomas explaining to a WSU police officer why he had his phone out.

“You can tase them, you can beat them with your (expletive) batons, you can choke them out, you can stomp them,” Thomas said to the WSU officer. “I will make sure you do not shoot them, because that will end their lives.”

Thomas said he’d seen one of his friends shot by police.

In the past five years, Pullman police have not used a firearm, according to use-of-force records.

Of the 72 more extreme uses of police force in the past five years in Pullman – including chokeholds, hits, kicks and knee kicks – approximately one out of five came from Wine- gardner.

Individual officers’ arrest rates and number of uses of force will be related to the shifts they choose and areas they work in, Jenkins said, adding that Gordon and Winegardner choose graveyard shifts near WSU’s campus, where police run into more criminal activity,

Despite working different beats, a handful of officers arrested people at rates close to the city’s demographics. Overall, three out of four officers arrested Black people at double or more the Black population rate.

Another factor in disproportionate arrest rates could be callers. More than 60% of incidents Pullman PD respond to are non-officer-initiated, meaning police are responding to calls, Jenkins said.

Pullman police get refresher courses on cultural competency each year, Jenkins said, but the best way to avoid biased policing is hiring the right people.

When asked if he’d hire someone whose actions led to a large settlement in an excessive force lawsuit, he said it would depend on the circumstances. The presence of a lawsuit without a verdict would not be enough on its own to disqualify a job candidate, he said.

“I believe in other jobs, if you slip up more than once, you’re out,” Bingham said. “(Gordon) is a police officer, and his only job is to protect and serve the community he’s in. I don’t know who he is as a person outside of his job, but we’re talking about lives. There are things after this. What’s that person’s mental state supposed to be after you’ve done this to them? How are they supposed to go on with their life?”

Bingham said he knew how to interact with police. His uncle is a police officer, and he knew to stay calm. But Black men have reason to be scared, he said.

In the police car, when Gordon asked if Bingham knew who had been recording the scene with his phone, Bingham started to cry.

“Sir, to be honest, I have no idea what happened after you Tased me. I don’t know who was trying to record,” Bingham said through tears. “We’re in a time period where a lot of African American males are being shot unarmed, so I think he was just recording because he doesn’t want that to happen.”

Gordon told Bingham, in an exchange captured on dashcam footage, that he feels the situation too, and lives it every day.

The department implemented body cams in 2013, Jenkins said, before the Ferguson, Missouri, police shooting of an unarmed 18-year-old Black man in August 2014 that sparked a national movement.

“We wanted to be transparent, we wanted to have that accountability, and we knew that the community would hold us accountable,” Jenkins said. “If the community has issues with how we’re doing things then we want to make adjustments.”

Body cam footage did lead to Bingham’s charges being dropped, he said, but it hasn’t led to accountability.

“There just aren’t enough eyes on them,” Bingham said. “They can get away with anything.”