There’s a long list of people who want to take on Jay Inslee, but five have the best chance

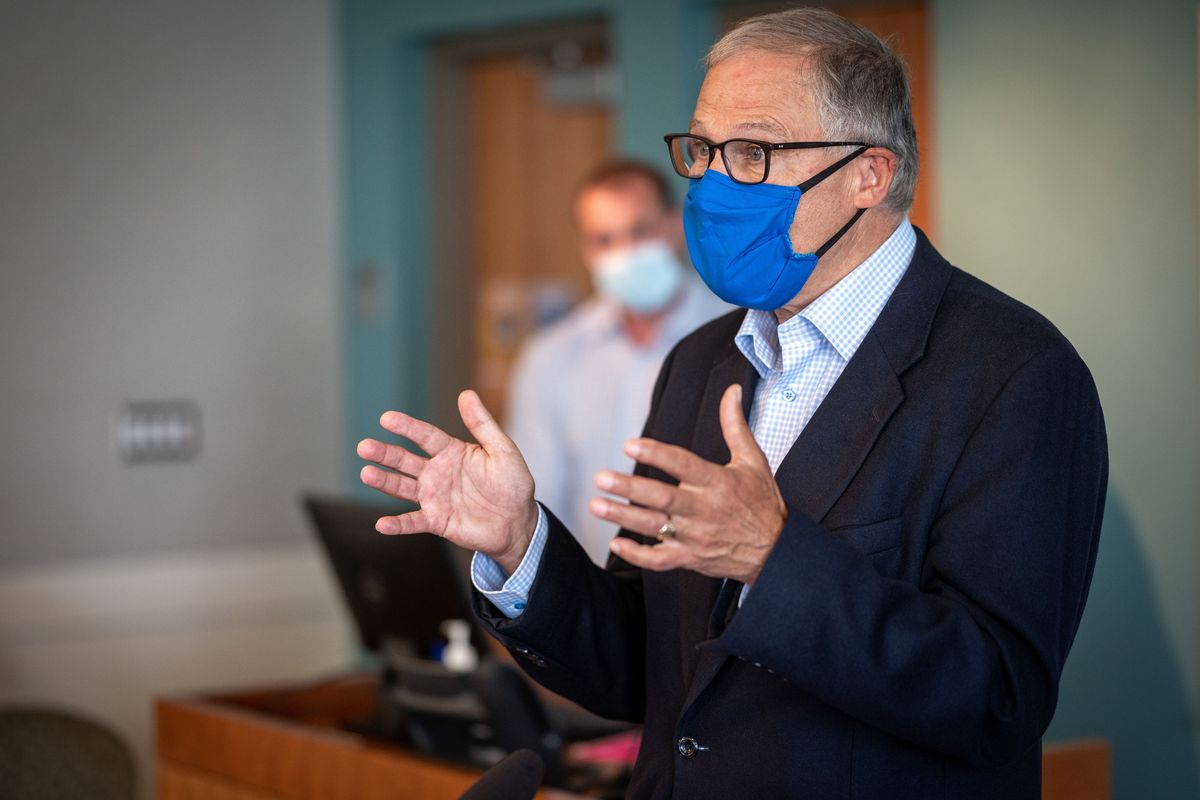

Gov. Jay Inslee meets with the press on Thursday, June 25, 2020, at Washington State University’s Spokane’s Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Sciences building. (Colin Mulvany/THE SPOKESMAN-REVIEW)Buy a print of this photo

With Washington fighting a viral pandemic and expecting a multibillion-dollar shortfall in its main budget over the next three years, one might think the list of people wanting to be its chief executive would be relatively short.

Not so. The current occupant wants a rare third term, and 35 challengers want to replace him.

The list of candidates for governor on the Aug. 4 top-two primary will be the longest in history, but with a 36-way split of the vote, it seems unlikely incumbent Democrat Jay Inslee won’t advance to the general. The race for the other spot is likely among five Republicans who are actively campaigning and raising money as they try to convince voters they are the best choice to deny Inslee another term.

Alphabetically, those top five GOP challengers are:

Loren Culp, the Republic police chief, first drew attention in 2018 when he announced he would not enforce a newly approved voter initiative that put new limits on the sale of semiautomatic rifles. He argued that Initiative 1639 was unconstitutional, although it hasn’t been successfully challenged in court.

Anyone with a sixth-grade education or common sense would know that by reading language of the state and federal constitutions, Culp said. “You don’t have to wait for a judge to know you would be infringing on someone’s constitutional rights,” he said during a radio interview.

But that stand, which was repeated by some other law enforcement officials in the state and described as grandstanding by others, earned Culp the support of gun rights advocates, which can be a significant bloc of votes in the Republican Party and among independents who can also vote in the primary.

He vows not to sign any bill the Legislature sends him that he believes violates the state or federal constitution, or that requires a tax increase.

Like many Republicans unhappy with the growth in the state budget, Culp insists Washington has a spending problem, not a revenue problem. He’s critical of the state’s approach to the homelessness problem through investments in more housing, saying that doesn’t get at the core problems of drug addiction and mental health concerns.

He advocates “tough love” for drug addicts that involves treatment and enforcement of drug laws, and “zero tolerance” for drug dealers.

Tim Eyman is probably the best-known member of the Republican field. He’s been sponsoring and promoting ballot measures for two decades, mainly on limits to state taxes and fees, and may be second only to Inslee in terms of name recognition. Like Inslee, not all of it is positive.

For years, legislators and other government officials who disagreed with his proposals challenged him to run for office if he wanted to change what they were doing. Until this year, however, Eyman demurred, claiming he was representing the voice of the people.

This year, however, Eyman switched course and brought his frenetic style of campaigning to the chase for the state’s top job. Although restrictions on gatherings can limit the size of his audience, he has tried to maximize his exposure with “news” events that he emails out to supporters, usually with a plea for a contribution.

In the first week of July, he held a press conference on the Thurston County courthouse steps to file a lawsuit against the mandate to wear face masks; a press conference in a Sea-Tac Airport parking lot challenging facial recognition software; and a rally on the steps of the Temple of Justice before the state Supreme Court heard arguments on his latest $30 car tab initiative. He read the Declaration of Independence on Facebook Live and spoke at a July 4th event at Oak Harbor, and on Monday he was at a Seattle City Council hearing on a proposed job tax, where he told a council member she should be in jail.

Along with his tax-fighting credentials, Eyman touts his support of Second Amendment rights and President Donald Trump, opposition to abortion and sanctuary cities, among other hot-button GOP topics.

He refers to the stay-home orders to fight COVID-19 as “Inslee’s lockdown” and looks for votes outside of metropolitan Seattle, where his initiatives have often struggled.

“Washington has a Seattle Legislature, a Seattle Supreme Court and a Seattle governor,” he argues in a video voter’s statement. “Enough. It’s time one branch of government represents the rest of us.”

That description doesn’t account for the fact that Eyman lives in Bellevue, about as close to Seattle as Inslee’s home on Bainbridge Island; the top leaders of both houses of the Legislature in both parties are from outside Seattle; and the chief justice of the Supreme Court is from Spokane Valley.

Joshua Freed, who operates a real estate investment company, starts his campaign pitch with a standard challenger’s question, asking voters if they are “better off now than four years ago.” It’s a question that could have extra resonance during a pandemic that generated business closures, an economic slowdown and sharp rise in unemployment.

Freed got his start in politics by winning a seat on the Bothell City Council and was later chosen by the council to be the city’s mayor. He branched out beyond municipal politics, leading a local initiative to block proposed heroin injection sites in King County, which had been given a green light by the local health board. Initiative 27 got enough signatures to qualify for the ballot, but a court later ruled the ballot measure couldn’t be used to block the health board.

Freed accuses public health officials of “pushing heroin injection sites instead of preparing for a pandemic,” although the fight over injection sites was several years before COVID-19 surfaced.

Republicans in the Legislature have tried, so far unsuccessfully, to change state law to block the sites, but some local governments have banned them.

To help restore the economy, Freed touts his work on the Puget Sound Economic Development Committee, the East King County Chambers of Commerce, and his service as mayor when downtown Bothell got a major revitalization. He’s also been involved in international aid programs in Kenya and the Philippines, and says he’ll donate the governor’s salary of $187,353 to charity.

Phil Fortunato is the only one of the five leading Republicans currently holding elective office, serving as the state senator for a district that includes suburban enclaves of Pierce and King counties like Auburn, Sumner and Enumclaw. He emphasizes that in his pitch to voters, noting that the state will face an $8 billion shortfall when the Legislature meets next year to revise the budget.

“This is not the time for on-the-job training,” he said. “You don’t have to ask me what I’m going to do, you can see what I’ve already done. Check my voting record.”

Known for fiery speeches on the Senate floor, Fortunato is a dependable voice and vote against any kind of tax increase and any proposal that involves restrictions on gun use or ownership.

Like Culp, he calls for “zero-base budgeting,” a process by which government agencies start from scratch and must justify the amounts they get. He notes, however, that the state’s budget is too big to do that all at once, and would divide the budget into four parts, with one year for each part, so the process would stretch over four legislative sessions – or a governor’s term.

Rather than increase spending on public schools, which get about half of the state’s general fund budget, Fortunato proposes allowing districts to seek waivers on state mandates as a way of saving the schools money that can then be redirected to other costs.

To spend more on transportation, he’d redirect the sales tax collected on vehicle purchases from the general fund to the state’s separate transportation fund that covers roads, highways and bridges.

Raul Garcia, a Yakima physician who has worked in emergency rooms and in recent years operated a clinic in that central Washington city, has the least political or government experience of the five, aiming high in his first run for office.

Born in Cuba, Garcia’s family emigrated to the United States when he was 11. In his native country, he says he saw the effects of big government and tyranny.

He’s critical of the state’s response to COVID-19, saying that confusion was understandable when the new virus showed up, but the lockdown lasted longer than necessary and the state didn’t focus on preventing hospital overloads or do enough to protect vulnerable people like those in nursing homes.

“The time to reopen the economy was when hospitals began to lay off nurses and began to risk bankruptcy during late spring,” he says in his discussion of the virus on his campaign website. He supports wearing face masks voluntarily, but opposes a government mandate, and says students need to return to the classroom this fall.

His campaign hit a bump last month when a video was released of a DUI stop and arrest he had in 2014. Garcia released a statement admitting he’d made a mistake and arguing he was a better leader for learning from it.

“By the grace of God, no one was hurt and I was humbled,” he said.

But it also received a boost in recent weeks, with a series of major endorsements from some well-known figures in the state GOP, including former Gov. Dan Evans, former Sen. Slade Gorton, Senate Minority Leader Mark Schoesler of Ritzville and Sen. Curtis King of Yakima, and Spokane County Sheriff Ozzie Knezovich.

Whoever makes it through the Aug. 4 primary, they’ll face a well-funded Inslee, who has already raised more than $4 million for the campaign. By comparison, Freed has raised more than $1.3 million, Culp more than $780,000, Eyman about $375,000, Fortunato about $191,000 and Garcia about $154,000.

There are 10 other candidates claiming to be some form of Republican – two list themselves as “Trump Republicans” and one as “Pre2016 Republican” – but none has raised significant amounts of money. Neither have the four other Democrats who filed for the job, or the wide array of third-party or invented parties some of the other candidates have listed.

Along with the campaign funds at his disposal, the challengers must contend with the fact that Inslee doesn’t have to campaign to be in the public eye. With the state continuing to struggle with COVID-19, he’s holding news conferences at least twice a week to do things that some voters support and others oppose, such as urging them to wear face masks, wash their hands and practice social distancing, while the state slowly reopens its economy.

He’s also made recent trips around the state, including to Spokane, Yakima and the Tri-Cities, to talk about the need for those precautions and to talk with local health officials.

The pace of that reopening was criticized by many local elected leaders around Washington in June as too slow. In recent weeks, some of those critics have been muted by the fact that their counties have seen increases in the number of residents testing positive for the virus and rising patient counts in hospitals.

But Inslee still faces a budget with a yawning gap of about $8 billion between what the state was planning to spend over the next three years and the amount of money it can expect to come in because of economic slowdown. He has ordered state agencies to propose 15% cuts to their budgets and ordered furloughs for state workers, but is currently not calling for legislators to return for a special session.

Republican legislators argue the state needs a special session so that they can have a say on what gets cut out of the budget, and a debate over the scheduled raises for those state employees. Any GOP challenger who faces Inslee in the fall is likely to take up that refrain and demand that the governor promise not to raise taxes to cover any shortfall.

Editor’s note: An early version of this story failed to report an Eyman appearance on July 4th.