Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical “Hamilton,” about one of America’s more interesting founding fathers, has been a huge hit everywhere it’s played: Off Broadway, on Broadway, a series of national tours and, now, on Disney+. But how closely does the storyline of the show you watched this weekend match up with historical fact? In places: Not very closely.

A history of “Hamilton”

How “Hamilton” went from a lengthy historical book to a hit Broadway musical:

April 26, 2004: The Penguin Press releases historian Ron Chernow’s 818-page biography of Alexander Hamilton. It becomes a best-seller.

July 2008: While on break from his hit Broadway show “In the Heights,” Lin-Manuel Miranda takes Chernow’s book with him on vacation in Mexico. Inspiration strikes him to set Hamilton’s story to music.

May 12, 2009: Miranda is invited to perform at the “White House Evening of Poetry, Music and the Spoken Word.” Instead of music from “In the Heights,” he performs the first song from his “The Hamilton Mixtape” project – a song that will later become the musical’s opening number.

Jan. 11, 2012: Miranda now has several songs done. He performs them as part of a “Hip-Hop Song Cycle” at the Lincoln Center’ American Songbook series.

July 27, 2013: Miranda performs a workshop production of his work at the Vassar Reading Festival. By this point, he has the entire first act and three songs of the second act done. Three cast members of this workshop production will join the off-Broadway cast a year-and-a-half later.

July 29, 2014: Tickets go on sale for Miranda’s new show – now named just “Hamilton” – to premiere in January, off-Broadway at New York’s Public Theater. Tickets sell quickly. Miranda tweets that he’s “overwhelmed by your response to Hamilton tix on sale.”

Jan. 20, 2015: “Hamilton” premieres at the Public Theater. Its entire engagement sells out. It wins eight Drama Desk awards, including Outstanding Musical.

Aug. 6, 2015: “Hamilton” moves to the Richard Rogers Theater on Broadway.

Sept. 25, 2015: The original Broadway cast recording of “Hamilton” is released on CD. It debuts at No. 12 on the Billboard 200 album chart and will peak at No. 3. It will also spend time at No. 1 on the Billboard rap album chart.

Sept. 28, 2015: The MacArthur Foundation names Miranda a “genius grant” fellow.

Feb. 15, 2016: The “Hamilton” cast recording wins a Grammy Award for Best Musical Theater Album. While accepting his award, Miranda raps his thank-yous.

April 18, 2016: “Hamilton” wins the Pulitzer Prize for Drama.

May 3, 2016: “Hamilton” is nominated for 16 Tony Awards – the most ever by a single production. At the awards ceremony a month later, “Hamilton” wins 11 Tonys, including Best Musical, Best Original Score, Best Book of a Musical, Best Actor, Best Actress, Best Featured Actor and Best Featured Actress.

Oct. 19, 2016: While “Hamilton” still runs to sold-out audiences on Broadway, a Chicago production of “Hamilton” opens at the CIBC Theater. Miguel Cervantes plays Miranda’s role as Hamilton.

March 10, 2017: The first national U.S. tour of “Hamilton” begins at the Orpheum Theater in San Francisco. A second tour will begin 11 months later.

Nov. 21, 2017: “Hamilton” opens at the Victoria Palace Theater in London. It will go on to win seven Oliver Awards the next year, including Best New Musical.

Jan. 11, 2019: The third U.S. tour of “Hamilton” opens with a three-week engagement in Puerto Rico. Miranda returns in the lead role.

July 3, 2020: Disney+ begins live-streaming “Hamilton” – with its original Broadway principal cast – that had been recorded over two nights in June 2016.

Fact-checking the big Ham

To give Miranda credit, “Hamilton” makes it clear from the start that it’s not aiming at historical accuracy. For starters, the show features a multiracial cast playing events that happened in and after the birth of the country in the 1770s – when most of America’s Black population was slaves. While Hamilton himself was born in the West Indies, he was most definitely white. And George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr are usually played by Black actors. None of them was Black, obviously.

All this is intentional. “We’re telling the story of old, dead white men but we’re using actors of color,” Miranda told the Hollywood Reporter in 2015. “And that makes the story more immediate and more accessible to a contemporary audience.” Miranda told the Atlantic: “This is a story about America then, told by America now.”

The Huffington Post pointed out that by casting Black, Latino and Asian Americans, Miranda is ”showing how irrelevant the Founding Fathers’ whiteness is to their claim on the country.”

On the other hand, Miranda told the Atlantic – also in 2015 – that he “felt an enormous responsibility to be as historically accurate as possible.”

Aside from matters of diversity – and, you know, the fact that everybody raps – here are other ways in which the musical differs from real life:

SLAVERY

▪ It’s true that Hamilton was a member of the New York Manumission Society, formed in 1785, that advocated for gradual emancipation of slaves in that state. But before he moved to America, Hamilton worked for a slave trading company in St. Croix. Louisiana State University history professor Nancy Isenberg says Hamilton himself once bought two slaves for $250.

“Imagine if one of the songs in the musical was ‘$250,’ ” Isenberg told the Associated Press. ”This would make everyone in the audience squirm and scream and it would completely undermine the heroic message and the progressive Hamilton that they want and they crave.”

POLITICS

▪ Hamilton liked big banks. He mistrusted the general population of the United States and, at one point, called for a president to have king-like powers and for a Senate that would serve for life. Princeton history professor Sean Wilentz told the New York Times that Hamilton “was more a man for the 1% than the 99%.”

▪ The show gives the impression Thomas Jefferson spent the Revolutionary War in Paris. Jefferson spent the war in the Continental Congress and as governor of Virginia. He didn’t replace Benjamin Franklin as minister to France until 1784.

▪ Hamilton did not ask for Burr’s help to write “The Federalist Papers,” a series of essays published in 1787 and 1788 in support of adopting the new Constitution. Instead, Hamilton wrote 51 of them, John Madison wrote 29 and John Jay wrote five.

▪ John Adams did not fire Hamilton as he did in the show. In fact, Hamilton resigned as Secretary of the Treasury on Dec. 1, 1794, two years before Adams became president.

PERSONAL LIFE

▪ Angelica Schuyler’s relationship with Hamilton is exaggerated greatly. In the show, she tells him her obligation is to marry a rich man because her father has no sons. In fact, Philip Schuyler had 15 children, including two sons. The real reason the real Angelica couldn’t marry Hamilton: She was already married with two children of her own.

▪ In “Take a Break,” 9-year-old Philip Hamilton says “I have a sister, but I want a little brother.” In fact, Philip already had two younger brothers at the time.

▪ In the show, Jefferson, Madison and Burr approach Hamilton about his affair. In fact, it was James Monroe and two others. Monroe was a close friend of Jefferson. In 1797, journalist James T. Callender wrote and distributed a pamphlet accusing Hamilton of infidelity and of a financial scheme, which damaged Hamilton’s reputation. Hamilton blamed Monroe for leaking the story of his affair.

▪ In the show, Eliza leaves Hamilton after news of his affair is made public. Chernow’s book makes it clear that Eliza was more angry with those who revealed the affair than she was with Hamilton himself.

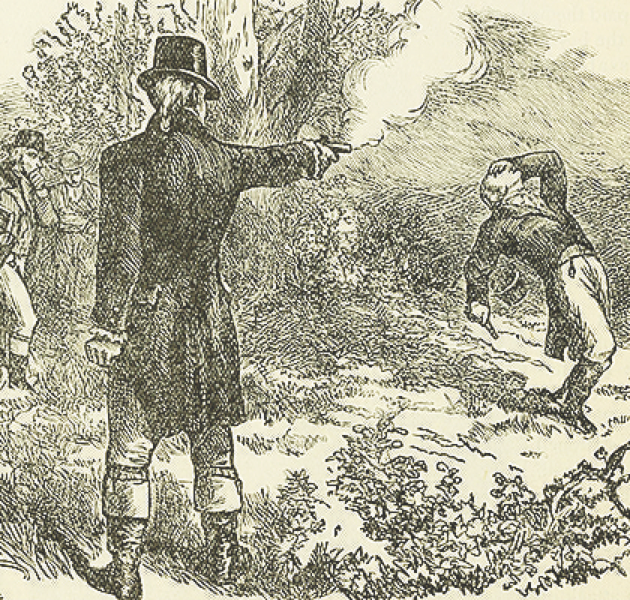

DUELS

▪ In “Blow Us All Away,” a grown-up Philip and George Eacker fight a duel before the 1800 presidential election, in which Eacker kills Philip by firing on the count of seven. In real life, the duel was fought on Nov. 23, 1801 – well after the 1800 election – and neither men fired for more than a minute after the count. Eacker finally shot, hitting Philip in the hip. Philip died the next day.

▪ In the show, Hamilton endorses Jefferson during a tie vote in the 1800 presidential election that puts Jefferson, rather than Burr, in the White House “in a landslide.” This leads Burr to challenge Hamilton to what will be a fatal duel.

First of all, a tie vote can hardly be called “a landslide.” Secondly, it was a different election in a different year that led to the duel: Burr ran for governor of New York in 1804.

Burr lost that election, but it came out later than Hamilton had written his father-in-law that Burr was “a dangerous man and one who ought not be trusted with the reins of government.”

Hamilton’s letter was leaked to the Albany Register newspaper. Naturally, Burr wasn’t amused. He and Hamilton exchanged a number of letters – which is fairly accurately depicted in the number “Your Obedient Servant.” As shown in the musical, it was this exchange that led to the duel that killed Hamilton.