One hundred and ten years ago Saturday, Black heavyweight champion Jack Johnson took on former white heavyweight champion James Jeffries. The result sent shock waves throughout the sport and throughout the country.

‘The Fight of the Century’

James Jeffries won the world heavyweight championship in 1899 and defended that title several times before retiring undefeated in May 1905. Jeffries, 35, had fallen out of shape and ballooned up to 330 pounds before he was persuaded – by a $100,000 guarantee – to get back into shape and to return to the ring for a highly publicized match against current champion Jack Johnson.

At the turn of the 20th century, professional boxing was very much a segregated sport. Johnson, 32, had won the “World Colored Heavyweight Championship” in 1903 and had then become the first Black world heavyweight champion in a match in Sydney, Australia, in December 1908.

The match was unabashedly billed as a contest between the Black champion and a “great white hope.” A temporary arena was built in downtown Reno, Nevada, to accommodate 20,000 fans.

The fight

Although Jeffries had worked himself back to his old fighting weight of 226 pounds, he proved to be badly outmatched. Jeffries lasted until the 15th round – in 110-degree heat under the hot Nevada sun – before Johnson sent the visibly tiring Jeffries to the canvas with a series of uppercuts. (This is the picture at the top of this page.) It was reportedly the first time in his career that Jeffries had been knocked down.

Jeffries struggled to his feet, but Johnson stepped up with a left hook that sent Jeffries through the ropes.

Jeffries was helped to his feet by one of his assistants and a fan (the man on the left, here, wearing a hat) ...

... but as soon as he staggered to his feet, Johnson stepped up again with another devastating right.

Jeffries tried to get up again, but his manager jumped into the ring to stop the fight. Johnson won with a technical knockout.

The aftermath

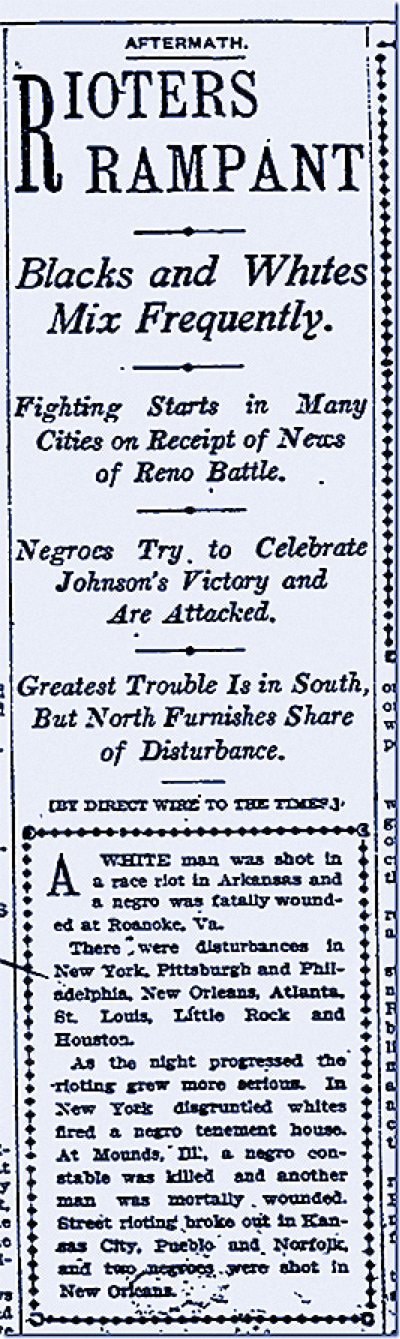

In those days before radio, television and the internet, sports fans would gather around newspaper buildings where announcers with megaphones would breathlessly read a play-by-play of big events telegraphed in real time.

This event was a little different, though, in that it attracted a large number of Black sports fans, who were elated at a powerful victory by Johnson. Many white boxing fans, on the other hand, were not pleased with the outcome.

The result: Jubilant Black fans around the country found themselves under attack.

▪ Eleven separate riots broke out in New York City when mobs of whites stormed into Black neighborhoods, setting fire to buildings and attempting to hang two Black men.

▪ In Columbus, Ohio, 400 Black fans held a victory parade. Whites broke up the parade with brawls.

▪ Blacks celebrating the victory in Pittsburgh were clubbed by police.

▪ More than 300 white sailors roamed the streets of Norfolk, Virginia, looking for Blacks.

▪ Three Black men were killed in Shreveport, Louisiana.

▪ Two Black men were killed in Little Rock, Arkansas.

▪ Two Black men were killed in Omaha, Nebraska.

▪ And so on, in more than 50 cities. Fearing more of the same, several state and local governments would ban the showing of a movie of the fight.

The postscript to the story

Two years later, Johnson would be arrested for violating the Mann Act against “transporting women across state lines for immoral purposes.” His crime: He had married a white woman.

Johnson would be convicted by an all-white jury and sentenced to a year in prison. He’d skip bail and flee to Europe. In 1920, Johnson would return to the U.S. and serve his year at the federal penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas.

Johnson would die in a car crash in 1946 in Franklinton, North Carolina, after leaving in anger from a diner that had refused to serve him. He was 68.

Over the years, presidential pardons for Johnson would be discussed and requested but never issued … until May 24, 2018, when President Donald Trump pardoned Johnson.

Actor Sylvester Stallone – who had written and starred in eight “Rocky” films between 1976 and 2018 – talked Trump into it.