Sunset will rise: Lights will stay on for popular Idaho drive-in, keeping a legacy going

Glancing to the left on his drive home on Jan. 6, the mangled metal of Sunset Auto Vue drive-in’s collapsed screen was a difficult sight for Chris Wagner, who ownsthe Grangeville theater, to bear.

Thanks to busted bolts, winds clocked at around 55 mph took down a screen built to withstand 110 mph gusts.

Jerry Selby, who lives in Cincinnati and installed the equipment in 2008, is considering coming out of retirement to repair it – depending upon how well he recovers from recent back surgery.

Selby, who started putting up screens in the 1950s with his father, has an impressive record: Of the thousands of screens he’s constructed over the years, Wagner’s was only the second to break.

Options have dwindled for drive-in theater repair, but Wagner said he will find a way to get the Sunset up and running for next season. Getting the screen repaired in 2008 was difficult, as well, for different reasons, he said. Wagner underinsured was underinsured at the time and mourning the death of his father, who was inextricably tied to the theaters.

But nothing was going to stop him from continuing his family legacy.

The Sunset was not the family’s first theater. The first was the indoor Blue Fox Theatre, which opened in 1930 and is on the National Register of Historic Places. The family also owns the Rex Theatre in Orofino. Wagner’s father closed the drive-in in 1986, when its longtime manager, Hank Bruegman, died.

“Dad just didn’t have the heart to open it back up,” Wagner said. “He said that was Hank’s baby, for the most part. He just loved being out there at the drive-in. He couldn’t wait to get the doors open in the springtime.”

After living in Alaska for 19 years, Wagner returned home in 1994. In the summer of 1998, against the advisement of his father and during a time most drive-ins were removing letters from the marquee, Wagner reopened the Sunset. Wagner was the “worker bee” while his father handled the books, but he assumes business must have been good.

“I was getting ready to leave his office and he says, ‘Oh, by the way, getting that drive-in back open is the best damn thing you’ve done since you’ve been home,’” Wagner said. “I took that as we must have made a little money out there that summer.”

Wagner wanted the drive-in opened because he wanted two screens to appeal to a wider audience.

Business remains good, Wagner said. It’s not unusual to spot quite a few out-of-state license plates in the lot: The Sunset has become a destination for those nostalgic for the drive-in experience.

The community is loyal and supportive, and people have offered to pitch in for repairs – including offers to launch a GoFundMe – but Wagner has assured them insurance will cover the repairs.

Paved paradise

Five drive-in theaters, including the Auto Vue Drive-In in Colville, remain in Washington. Wagner’s is one of six in Idaho. Across the country there are about 300.

According to a 1990 Spokesman-Review article, 1,041 drive-ins remained in the U.S., and two of those called Spokane home: the North Cedar Drive-In and the East Sprague Drive-In. North Cedar Drive-In would be the last when it closed in 1994.

The Spokesman-Review’s Dan Webster wrote about his experience taking in a double header at North Cedar, reflecting on the theater’s draw.

“The movies we’re about to see – ‘Days of Thunder’ and ‘Pretty Woman’ are new,” Webster wrote. “But the setting isn’t. It’s definitely a throwback to the ’50s, those days when America’s love affair with the automobile was still in full bloom.”

The first Spokane drive-ins, East Trent Motor-In and Auto Vue Drive-In, opened in June 1946, advertising themselves as “Movies Under the Stars” in the newspaper. Motor-In was showing “Doll Face” with Vivian Blaine, Perry Como and Carmen Miranda on opening night, while Auto Vue was screening “Murder My Sweet” with Dick Powell and Ann Shirley.

At its peak, Spokane had seven drive-ins, which catered to vastly different audiences, holding a mirror to Spokane’s eclectic, idiosyncratic nature: church services, B horror movies, softcore porn, used car swaps, cartoons, first runs and more.

“A decent drive-in offers use of the halfway-house pleasures we can’t get in our home or at an indoor theater,” Tom Sowa wrote in a July 31, 1981, edition of The S-R. “There are times when a large screen is always more desirable than a TV screen, just as there are times when sitting in a car in a drive-in parking lot, with the sounds of humanity mixing with a scratchy soundtrack, seems the appropriate remedy to an otherwise humdrum existence.”

In most cases, drive-ins folded because the land became more valuable than ticket and concession sales. Owners read the writing on the wall.

“Drive-ins are good ways to hold land,” David Schooler, Sterling Realty Organization board chairman, said. “You’ll make a little money, but you don’t make a lot. That’s one of the reasons you don’t see many in this state anymore.”

The East Sprague Drive-In, the second to last to fold, was the perfect example of the drive-in at its height. The theater grounds had a carousel, a mini train, airplane swings and more for children to play on. The theater offered heaters for the cars, allowing its operation to run year-round instead of seasonally. High school students earned spending money from tips cleaning windshields.

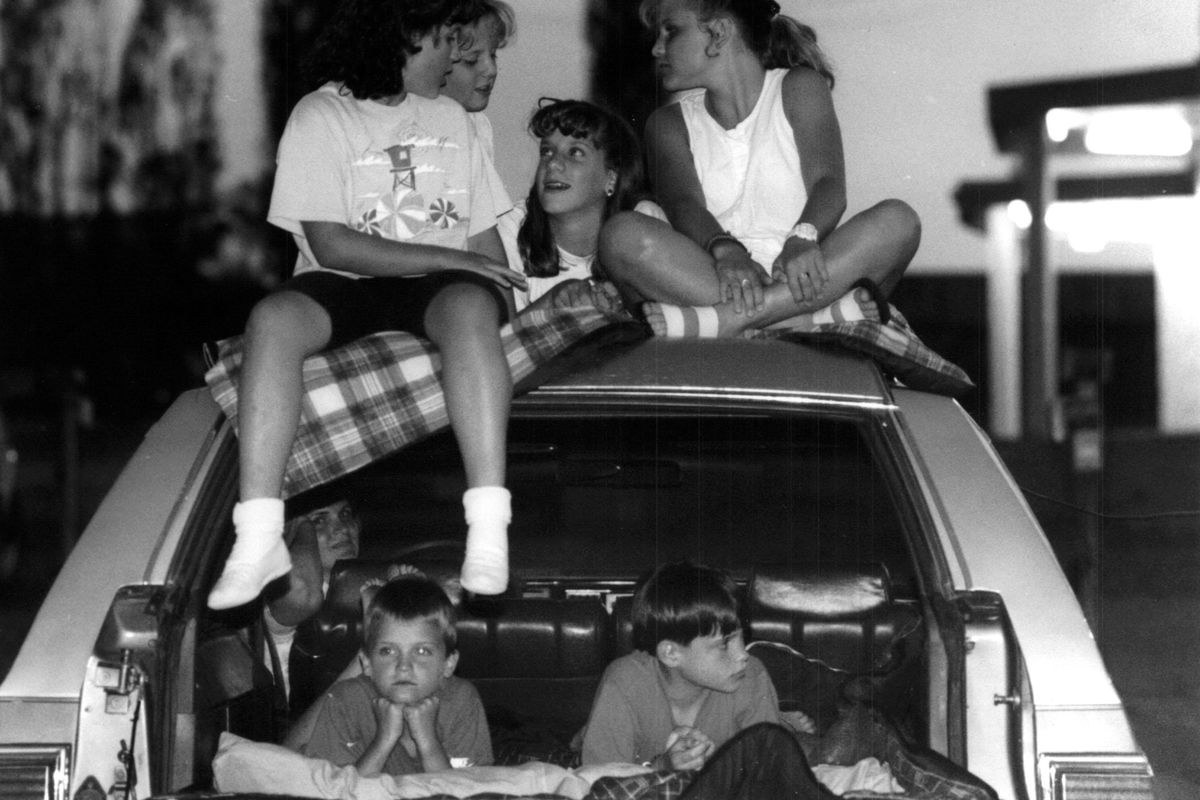

“We tried to have playgrounds so that little kids would have something to do if they weren’t as interested in the movie,” Schooler said. “We tried to make them all very family friendly. We knew that it drew from various ages, including people who arrived in trunks.”

The East Sprague Drive-In met its end when the property was bisected by Interstate 90’s Sprague interchange.

In 2000, Valley resident Doreene Andersen wrote for the S-R’s Voice section about her experience driving down East Sprague near the overpass, where the drive-in was. In her column, Andersen loses herself in memories while stuck in traffic, gazing at what was then a Koerner furniture sign but what had been the green sign and arrow of the East Sprague Drive-In marquee.

“Progress is a part of life in the Valley today, but we do pay a price,” Andersen wrote. “I know nothing will bring back the East Sprague Drive-In, but at least many of us have our memories. Honk, honk, honk! Looks like the light is green.”

Not all drive-in reminisces are as wholesome as Andersen’s. The Y Drive-In was one of two drive-ins under the direction of Morrie G. Nimmer, Group Theaters manager, that caused a ruckus by screening softcore porn.

The Y Drive-In was particularly contentious because a hill – which also housed Cedar Village Apartments – allowed onlookers to take in a free, albeit silent, show.

“A car filled with five teenaged boys was parked between two trees in a position where the full screen could be seen outside the fence,” The Spokesman-Review reported in 1976. “All of the underaged youths in the car said they had come for their first look at an X-rated show after reading in the newspaper about the conflict over pornographic films at the Y.”

Though concerned citizens at City Council meetings voiced the problem the vantage point would create for the apartment complex, Manager Randall C. Chapman told the newspaper the view had been more of an asset than a liability.

“From the balcony of the newly constructed Cedar Village apartments which are southeast of the theater, one 23-year-old tenant was watching the films,” The Spokesman-Review reported. “He said he and his wife did not mind the X-rated shows and often watched them together from the balcony.”

The Y Drive-In became Wendle Ford, cars replacing cars. The other theater known for its explicit content was Auto Vue Drive-In, but before Nimmer acquired it in 1965, it played much more wholesome content and even hosted church services on Sunday.

The Starlite Drive-In, owned and operated by Walter Hefner, truly marketed itself to a niche crowd, and even when it ended, Hefner continued its spirit in another project.

“People forget the kind of freedom and creativity the drive-ins had,” Hefner told The Spokesman-Review in 1987. “Today circuit bookers in Seattle or Portland book all the movies that play in Spokane’s theater chains, but at the Starlite I could show whatever I wanted.”

When the Starlite opened, Hefner stated an intention to play only family friendly movies and cartoons, but the theater became known as the only spot you could catch first-run B horror movies and makeshift film festivals, such as an Elvis Presley marathon.

“Sometimes the last feature in the series would finish after the sun came up so people would be staring at blank screens while listening to the last of the dialogue,” Hefner told the Spokane Chronicle in 1987.

For Hefner, movies were life, and his theater, like that of the Wagners, was a labor of love. His theater opened in ’72, after building for two years on a shoestring budget of $100,000. Hefner did most of the work himself, building as he acquired the funds.

Even after selling the land in 1985, his life remained devoted to movies. He took the $1 million he received for the land and reinvested much of it in a project to make his own movie, “The Ghosting.”

Pam Kingsley, a frequent Spokane Civic Theatre actor who played Amy Jessup in “The Ghosting,” said Hefner took the project seriously. She became acquainted with him when they were both acting in a Spokane Civic Theatre production of “Death of a Salesman.”

He attended a film intensive course on the East Coast, accumulated a hodge podge of filming equipment, hired a professional crew (including a snake handler) and paid more than fair wages to all involved.

“He was quite serious about this,” Kingsley said. “It wasn’t like, ‘Oh, I’m going to go to down to the barn today and make a movie.’”

For a base of operations, Hefner bought what was then the Swedish Baptist Church on Broadway, which burned in September 2017.

“It was kind of drafty, although he did get some heat put on eventually,” Kingsley said. “But it was this big, old, drafty, abandoned church, and he turned that into his set for this movie.”

Kingsley said participating in the film had been an opportunity she could not pass up.

“This was in the ’80s in Spokane, before Spokane was doing movies,” Kingsley said. “Walt was like a maverick. He sold his property and he took that money and most of it went into this.”