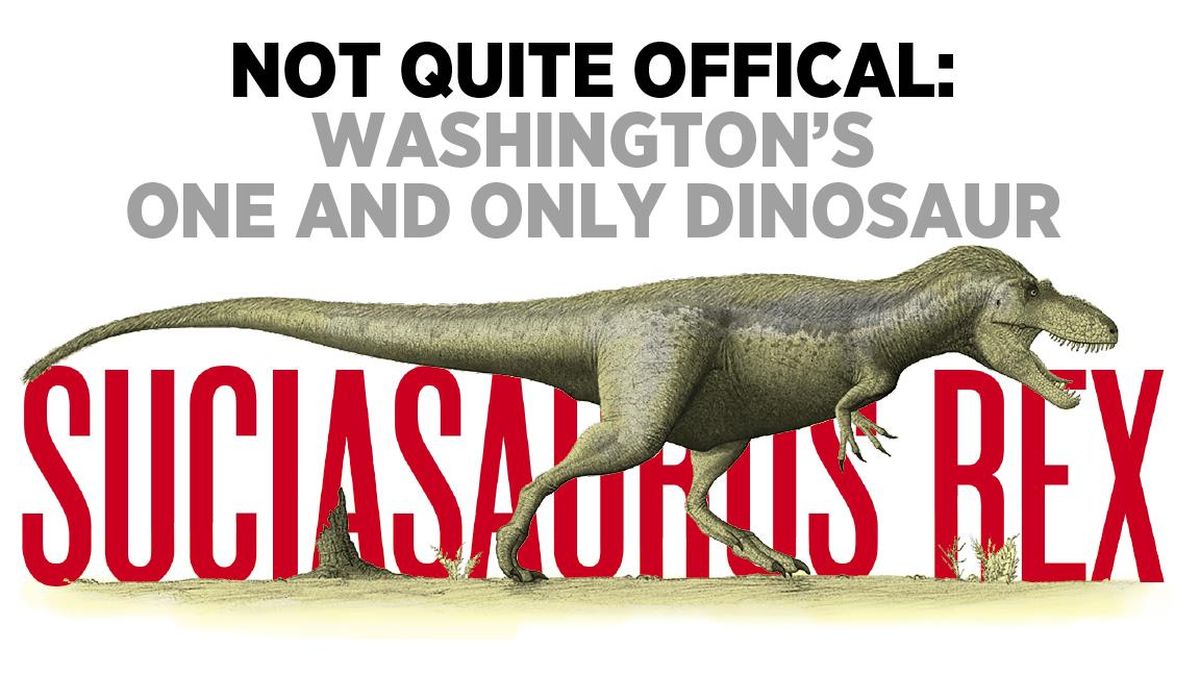

T. rex relative could become Washington’s official state dinosaur

Suciasaurus rex, a meat-eating predator that lived about 88 million years ago, may soon be the official state dinosaur, thanks to eons of geologic upheaval, a chance discovery and some civic engagement by elementary school students.

Regardless of whether the Legislature sees fit to bestow that official designation, Suciasaurus is the state’s only dinosaur – at least in terms of having some fossilized part of an extinct reptile found within the boundaries of Washington.

A forerunner of the better known Tyrannousaurus rex, which often gets starring roles in movies like “Jurassic Park,” Suciasaurus was smaller and lived about 15 million years earlier. Unlike the T. rex, it doesn’t have an official species name but rather a nickname derived from Sucia Island, the place where the fossilized remnant of its upper femur, or thigh bone, was found eight years ago.

In the peer-reviewed scientific paper on the fossil, its name is “indeterminate theropod dinosaur,” said Christian Sidor, curator of vertebrate paleontology at the University of Washington’s Burke Museum. Theropods are a family of dinosaurs that include the T. rex and the velociraptor and eventually evolved into birds.

“It’s a relative to Tyrannosaurus rex, probably,” Sidor said. “People want to put a name on it.”

Suciasaurus got “rex” added to its name – Latin for “king” – when it starred on a T-shirt for the museum.

Whether you call it Suciasaurus or indeterminate theropod, it is the first and so far only dinosaur fossil found in Washington. The odds are pretty good it could be the last because of the geologic and geographic circumstances surrounding its location and discovery, which also relied on some lucky timing.

When Suciasaurus was running around feasting on slower plant-eating dinosaurs during the Late Cretaceous Period – the Jurassic Period was about 100 million years earlier, despite what Michael Crichton and Steven Spielberg want you to believe – what is now Washington state was under water.

“We just don’t have the right types of rocks,” Sidor said.

Suciasaurus lived – and died – in a coastal area somewhere between the current location of Baja, Mexico and Northern California. It likely died somewhere along the coast, its body may have been washed out into shallow water where much of it fell apart or was carried off and eaten. But a portion of thigh bone settled onto the sea floor.

Theropods have distinctive thigh bones with hollow middle cavities. Based on the estimated femur size of slightly more than 3 feet, paleontologists can estimate it could have been between 30 and 35 feet long, which is a bit smaller than the T. rexes that lived about 15 million years later.

Theropods were the only known dinosaurs with that kind of thigh bone in what is now North America 80 million years ago, so even though the fossil isn’t enough to declare a new species, “there’s enough to know it’s a large carnivorous dinosaur,” Sidor said.

Down in the sediment on the sea floor, some small clams common to shallow water “found the bone and started living on it,” he said. That was fortunate because they also fossilized, and the clam fossils on the bone fossil help date it.

Over the eons, the marine rock formation that held the fossilized bone and clams was pushed upward and northward by tectonic forces that helped form the San Juan Islands archipelago. It ended up on Sucia, a small horseshoe-shaped island home to a state marine park that can only be reached by boat.

In 2012, a pair of Burke Museum researchers were walking along a beach on the island looking for fossilized sea creatures. They spotted something they recognized as a small section of some type of fossilized bone embedded in rock. They marked the location, and a crew returned a month later with a permit, excavated the fossil and took it to the museum for study. Not long after, a landslide covered that area of the shoreline. So if the fossil hadn’t been found and excavated by then, it would have been buried and remained in the rocks.

After several years of research, Sidor and UW graduate student Brandon Peecock wrote about the discovery of the first dinosaur fossil in Washington, describing its dimensions and likely relationship to other theropods that lived in North America some 80 million years ago. There’s not enough information to construct a full skeleton of indeterminate theropod, so the best they can say with certainty is it was a relative to the later T. rex, which was the biggest North American therapod with a length of 40 feet or more and lived just before dinosaurs became extinct.

That family of dinosaurs included many different sizes, Sidor said, and there’s not necessarily a straight evolutionary line from the Sucia Island fossil to the well-studied Tyrannosaurus, which has been found in far greater numbers in Rocky Mountain states.

“It’s more like branches on a bush,” he said of the theropod family.

The thigh bone is on display at the museum, and it may have been relegated to the status of state oddity if not for Amy Cole’s fourth-grade class at Elmhurst Elementary in Parkland.

While studying how a bill becomes law, the class hit on the idea of trying to make Suciasaurus the state dinosaur. Other classes around the state in previous years have mounted successful campaigns for other state declarations, such as the 2014 effort by Washtucna Elementary students to have Palouse Falls designated the state waterfall.

They did their research and last March contacted one of their legislators, Democratic Rep. Melanie Morgan, who introduced a bill to have Washington join 12 other states and the District of Columbia in declaring an official dinosaur. But that was past the deadline for considering new bills in the 2019 session, so the proposal was held over until this year, when it got an early spot on the House State Government Committee calendar this week and a generally friendly reception.

“It’s not just about us passing a bill, it’s about civic engagement,” Morgan told the committee. “It would make a difference for some of our most underrepresented students.”

The students are in the fifth grade now, Morgan said. They weren’t able to attend the committee hearing to make their pitch for the bill, but they will make the trip to Olympia for a signing ceremony if it passes, she said.