This column reflects the opinion of the writer. Learn about the differences between a news story and an opinion column.

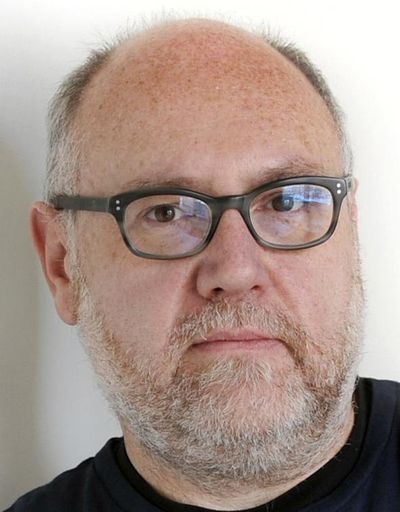

Shawn Vestal: Ceremonial gestures aside, honesty will make or break new City Hall relationships

The first night of the new era in city government was all sweetness and light.

Mayor Nadine Woodward sat on the dais for a portion of the City Council meeting on Monday, a unique move billed as a symbol of reconciliation and cooperation. She read a couple of proclamations, and it’s safe to say she did a very good job. I predict Woodward will be the best mayor any of us have ever had, in terms of reading written words aloud.

Council President Breean Beggs gave an introductory speech in which he made a note that the city charter does not create just a strong mayor; it also creates, he pointed out, a strong council. After a recent move approved at year’s end to hire more staff and rather rapidly – even rashly – jacking up the council’s budget, the council may be even stronger than before.

But Beggs’ emphasis was on the need for cooperation, and the need to avoid conflict, that stalemates progress.

All well and good. We should hope it augurs well for a better, more cooperative relationship at City Hall – especially better than the past year, in which Mayor David Condon’s administration seemed to have taken its ball and gone home, leaving jobs unfilled, dragging its feet on key priorities such as addressing homelessness, and prompting baffled council complaints about repeated refusals from the administration to answer questions and provide information.

As much as former Council President Ben Stuckart, Councilwoman Karen Stratton and the rest of the City Council majority became, for many, the focus of criticisms over combativeness at City Hall, the truth is that the council was often simply more outspoken in disagreement. But the passive-aggressive silent treatment from the administration, coupled with the haughty refusal to enact lawfully passed ordinances, was every bit as much to blame for the breakdown in communications.

That breakdown didn’t have much to do with what happens when the TV cameras are rolling. It wasn’t a breach of trust over a commemorative proclamation or the rubber-stamping of appointees. In fact, the ceremonial folderol was often in fine shape during the Condon-Stuckart years, with them appearing side-by-side and presenting a united front, even as things were bitter behind the scenes.

No, what will make or break the relationship at City Hall – and what broke the last one – isn’t what happens when everyone’s looking.

It’s what happens when no one is, and how honest you are about it.

It’s how you disagree, and whether you’re willing to listen.

It’s how you act when you don’t get your way.

It’s whether you tell the truth when you just don’t want to.

Those are important for everyone, of course, but especially for a strong mayor coming into office with a stronger council. Disagreements are coming. Controversies and political battle, like it or not. Mistakes will be made. How everyone in this new iteration of city government handles those will tell the tale.

To my mind, the honesty question looms largest. It requires no predictive ability to know that a time is coming when it will be more convenient for one party or another to lie than to tell the truth. It requires no predictive ability to know that this party might not really see this lying as lying, per se – lying to the news media doesn’t really count, lying when you think you have a good reason doesn’t really count, etc. We’re all experts at justifying the ways we cover our behinds, and politicians have more chances – and more reason, often – to do so than the rest of us.

But failures of honesty are corrosive and long-lasting. To see this, you need only think back four years or so to see what the Condon administration did when it found itself with a difficult truth to manage – the implosion of the mayor’s personally recruited police chief, Frank Straub.

The Straub affair was messy and complicated, but at its heart was a series of dishonest representations, intentional obfuscations and attempts to hide uncomfortable truths inside the city attorney’s office. The mayor claimed there was not a sexual-harassment complaint when his top lieutenant, Theresa Sanders, had been approached with a sexual harassment complaint and had acted to move the victim into another role, and leave Straub in place – at least until a different simmering pot boiled over, and he was subsequently given a rapid firing.

Condon would later say his comment about the complaint was honest, since there hadn’t been a formalized, paper complaint filed. Sanders lied to a reporter about the matter, and later – when she was slapped on the wrist for her statements by the city ethics board – said that her mistake was not that she should have told the truth but that she should not have spoken to the reporter in the first place.

Council members were not so shruggingly blasé. Feeling they had been lied to, as well, they initiated an investigation that discovered the administration had worked to delay the release of public records – which would reveal the damning extent of the knowledge they claimed they didn’t have – until after Condon’s re-election. The investigator concluded they’d withheld the documents purposely.

All the way, the mayor and his team defended themselves, denied, rationalized. They saw their various dishonesties as validated, as necessary to the larger work, of which they were the proper custodians, and seemed to view questions about what had happened as improper and impertinent.

It’s not like there weren’t conflicts between Condon and Stuckart beforehand. But the Straub affair, Stuckart has said, completely broke his trust in Condon. As someone who was on the other side of the administration’s misrepresentations, and stubborn defense of them, it strikes me as a rational response to lose trust in people who lie to you.

Which brings us back to Monday night, and the gestures of cooperation, and what they may or may not bode for the future.

Things didn’t go bad because Condon didn’t attend enough council meetings. They went bad, in large part, because he and his team didn’t heed a basic principle that is very crucial to effective representative government, but not always easy in politics: Tell the truth. Especially when you don’t want to.