Report: Washington State Patrol singles out Native American drivers

Twelve years ago, academic researchers working with the Washington State Patrol raised a warning flag: Troopers were searching drivers from minority communities, particularly Native Americans, at a much higher rate than whites. They recommended additional study.

That was the last time the WSP conducted a substantive analysis of the race and ethnicity of drivers searched by troopers.

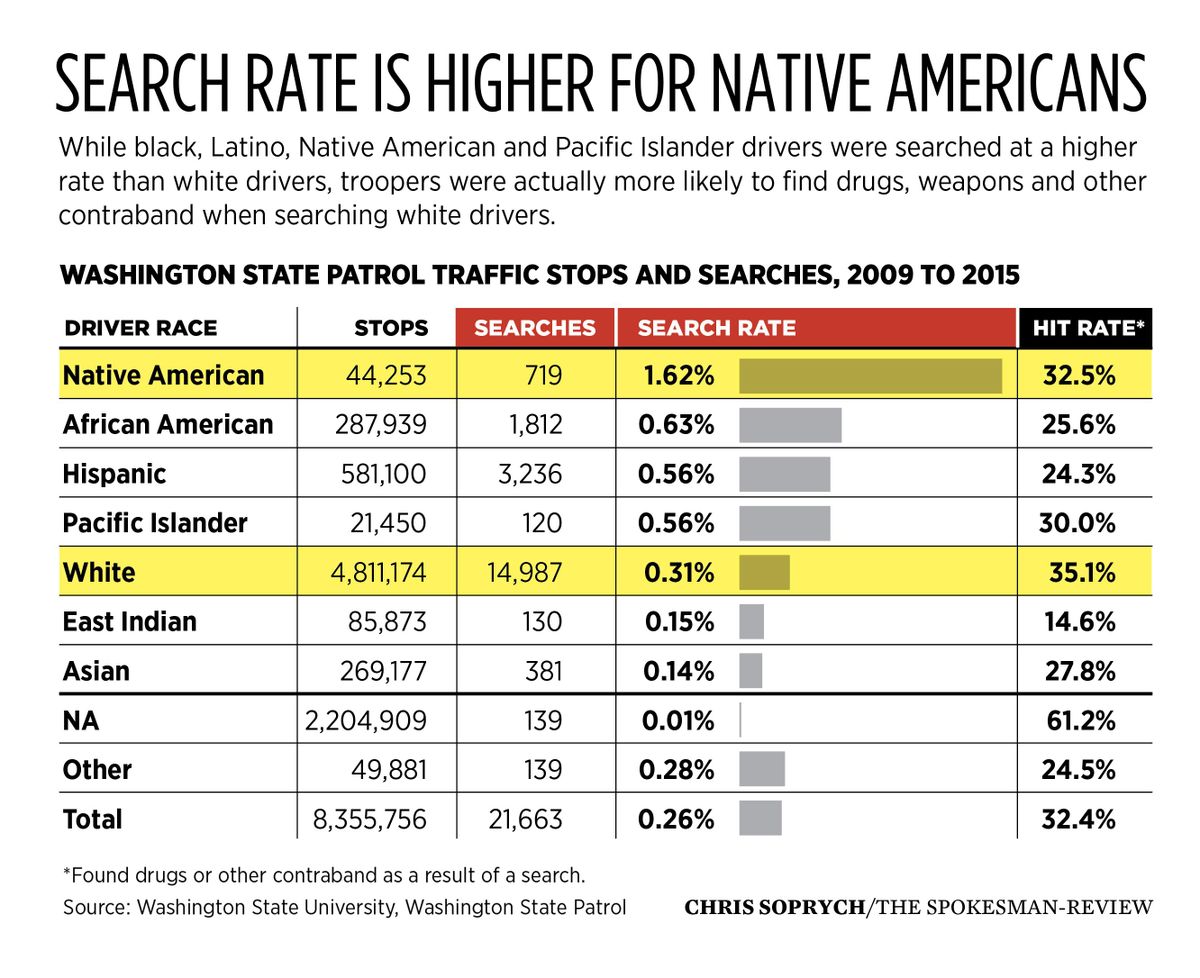

Meanwhile, troopers continued to search Native Americans at a rate much higher – more than five times – than that of whites, an analysis by InvestigateWest shows. The patrol also continued conducting searches at an elevated rate for blacks, Latinos and Pacific Islanders.

And yet when troopers did decide to search white motorists, they were more likely to find drugs or other contraband, records show.

WSP did not dispute InvestigateWest’s findings.

“Obviously the response to date is not adequate and obviously needs to be adjusted and needs to be advanced and new strategies need to be applied,” said Chris Loftis, the patrol’s communications director. “And we’re committed to doing that.”

Meanwhile, government records obtained by InvestigateWest through the Washington Public Records Act show that despite a state law that said WSP “shall collect, and report semi-annually to the Criminal Justice Training Commission” the race and ethnicity data of motorists stopped by troopers, the agency reported those findings just three times in 15 years.

InvestigateWest based its analysis on responses to more than 30 public records requests to three Washington state agencies; more than 50 interviews with current and former law enforcement officials, experts on criminal justice and civil rights, and people who had interacted with WSP; and data from millions of traffic stops provided by Stanford University.

The traffic-stop data was obtained by Stanford researchers through a Washington Public Records Act request and made available to journalists and researchers through the university’s Open Policing Project.

Lower bar to search motorists of color

Researchers of bias in policing say disproportionate stops and searches of racial groups can undermine the confidence that communities of color have in the police. It also can rig the system against people of color – because if whites are less likely to be searched, they’re less likely to be arrested, even if they’re committing crimes at the same rate as or higher than people of color.

It’s a national problem. Stanford’s analysis of more than 100 million state and municipal police stops across the country found “evidence that the bar for searching black and Hispanic drivers is lower than for searching whites.”

In Washington, experts cautioned that the data covers only state patrol searches, and can’t show what’s happening with local police departments.

Loftis, the WSP spokesman, said the agency is making strides to improve relations with the communities it polices, including hiring a tribal liaison in November. The agency says it’s in the process of hiring a second liaison who will work with Native American communities in Eastern Washington.

For many people from communities of color, InvestigateWest’s findings showed statistically what they have observed in person for years.

“You know, it’s always been that way,” said Norma Sanchez, a council member for the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation. “We would have never thought anybody else noticed it.”

InvestigateWest examined nearly 8 million traffic stops from 2009 to 2015, the most recent data available. The analysis focused on 22,000 incidents of what researchers call high-discretion searches, when troopers had the most leeway to decide whether to pat someone down or search a vehicle. Black drivers were twice as likely to be searched as white drivers, and Latinos and Pacific Islanders were about 80% more likely to be searched.

Robert Chang, a law professor at Seattle University who examined WSP stop and search data in the past, called the results of the InvestigateWest analysis “really disturbing.”

“What is the human cost of all of this?” asked Chang, who in 2012 co-wrote a refutation of parts of the Washington State University reports that cleared troopers of intentional racial profiling. “It’s a shame that we have let this go this long.”

Loftis noted that the WSU researchers whose 2003, 2005 and 2007 studies raised concerns about disproportionate searches of Native Americans couldn’t say race was the only factor that troopers used to decide whom to search. That’s partly because blacks, Native Americans and Latinos are more likely to be searched regardless of how much discretion troopers have. He also pointed out that the WSU researchers found factors such as the type of violation, the number of violations, the driver’s age and gender and the time and location of the stop “may have as important an impact on the likelihood” of a search.

But he said WSP agrees there is a disparity, and said that “is not acceptable.”

“There’s all sorts of things we can go back and forth on there, but we’re in basic agreement that minorities are searched at a higher rate, and we find less contraband,” Loftis said.

However, he also noted that complaints about bias accounted for little more than 10% of all complaints the state patrol fielded last year, and only 3/1000ths of 1% of all contacts troopers had with the public.

Required reports not filed

Washington keeps more detailed records of stops than most state police agencies. That started in 1999 when then-State Patrol Chief Annette Sandberg, after reading a story in the New Yorker magazine about police stops in New Jersey, ordered Washington troopers to keep detailed data on the race and ethnicity of people they stop.

The decision was ahead of its time and controversial. Some troopers were disciplined for refusing to accurately record data, according to a 2015 training presentation to cadets that noted, “the rest of the state law enforcement agencies made sport of the patrol for having to do this stuff.” The next year, the Legislature made the data collection a legal requirement.

But after the WSU studies that started in 2003 and ended in 2007, the patrol hasn’t done much with the information, records and interviews show. The 2000 state law said WSP “shall collect and report” the information “semi-annually,” which is defined by dictionaries to mean twice a year. The requirement for WSP to report to the training commission was dropped three years ago – in legislation sponsored by Reps. Tana Senn, D-Mercer Island; Bruce Chandler, R-Granger; and Timm Ormsby, D-Spokane – in the interest of reducing government paperwork. Even today, some local police departments voluntarily submit reports about their traffic stops to the CJTC. According to documents InvestigateWest obtained through a public records request, the Patrol submitted the reports only in 2001, 2008 and 2009.

Loftis said the agency doesn’t have the capacity to conduct its own reviews and halted the WSU studies because of lack of funding during the 2008 recession. WSP didn’t regularly submit reports to the CJTC, Loftis said, because officials determined “it was a one-time requirement” that the agency complied with when it submitted the 2001 report to the state Legislature. The statute said the patrol was required to submit a report to the Legislature by December 2000. In a separate provision, the law said the patrol was to submit semiannual reports to the Criminal Justice Training Commission.

What it looks like on the ground

As she drove into Omak for a Friday meeting one morning in July 2017, Sanchez, the Colville council member, passed three Washington State Patrol cars parked along the main artery from her nation’s reservation to the northern Washington city bordering the reservation. Curious, she drove down the street and pulled over to watch.

State Route 155 curves north from Grand Coulee Dam at the southern edge of the Colville reservation to the tribal headquarters at Nespelem, then descends westward to Omak. The city of fewer than 5,000 people serves as the commercial center for the rest of Okanogan County and the sprawling Colville reservation, which includes parts of Ferry and Chelan counties. Anyone on the reservation needing a new cellphone, groceries or construction supplies must take Route 155 into Omak. On that day, Sanchez said, she saw state troopers waiting just inside the city limits.

As she pulled into town, a trooper had just finished writing one ticket and immediately pulled over another vehicle, Sanchez said. She watched as the trooper took IDs and questioned everyone in the vehicle. Less than 30 minutes later, as she drove by again, a trooper had pulled over another vehicle and was again questioning its passengers. She recognized each as a Colville Tribes member.

“I watched a lot of non(tribal) members drive by, but then I would watch them stop tribal members,” she said. “So I didn’t know if they were profiling us or not, but everybody I did know I contacted them and asked them, ‘Why did you get stopped?’ Every one of them were for small infractions and minor vehicle issues.”

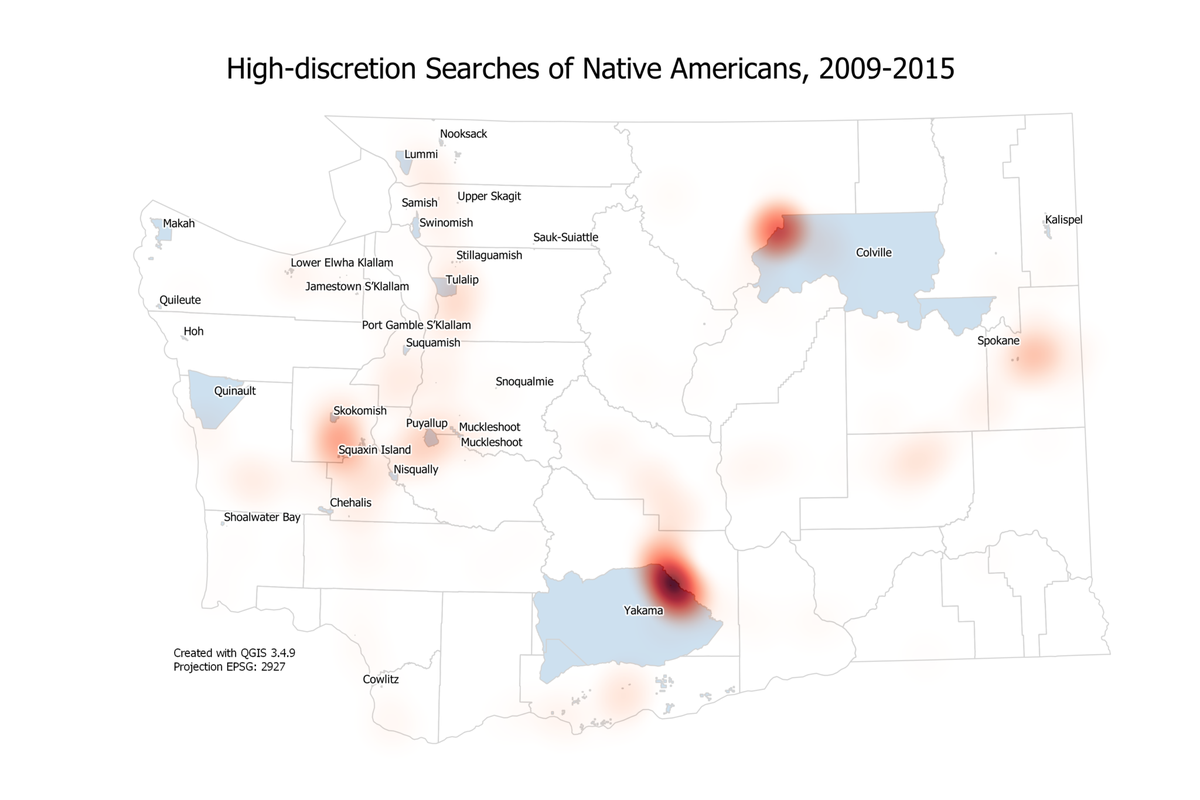

InvestigateWest’s analysis found that not only are Native Americans more likely to be searched, but that many of those searches happen on the edges of reservations. The analysis found two of the highest concentrations of searches of Native Americans by state troopers are on U.S. 97 where it enters the Colville Reservation at Omak, about a mile from its intersection with State Route 155, and more than 130 miles south, where the same highway enters the Yakama Reservation. Nearly one-third of high-discretion searches of Native Americans by state troopers happen on those two stretches of highway.

That tracks with many Native Americans’ perceptions of how the police treat them in Eastern Washington. Steven Graham, a defense attorney in Spokane who served as the elected prosecutor in Ferry County from 1998 to 2002, said it’s a problem for police departments across the region.

“A lot of times you’ll just be driving down the road and you’ll see younger Native kids in a black Honda with two police cars there,” Graham said. “They’ve got the kids out of the car and you just know they’re getting a million questions. I think that’s just kind of how it works.”

Loftis, the WSP spokesman, said troopers are not deployed to target drivers traveling to and from tribal land. Rather, he said, some major transit routes in the state happen to cut through reservations, he said. The state has limited authority on most tribal land.

“So while one might presume the troopers are there because of an unfair focus on tribal traffic, in reality they are there because those spots are where the traffic is, tribal and nontribal alike,” Loftis said.

Policing experts say tactics like hanging out on the edges of reservations or subjecting one group to more rigorous searches exacerbate existing tensions between police and the communities they patrol, regardless of whether the policies are racially motivated.

And it adds to the perception in Native American communities that the government is antagonistic toward native people, said Matthew Fletcher, a professor at Michigan State University College of Law and director of the Indigenous Law and Policy Center.

“I see this in other areas, too, like child welfare where social workers tend to jump the gun on going in and looking at an Indian family’s home, and grabbing a kid more quickly than they do with other races,” Fletcher said.

‘People are afraid of police’

What the data can’t show is whether state troopers are intentionally stopping and searching drivers based on their race. One of the more common explanations given when researchers find evidence of discrimination but can’t prove it’s intentional is that it’s a result of “implicit bias,” the term used to describe how unconscious stereotypes play a role. This stereotyping is driven by a range of personal experiences, including how different races and ethnicities are presented in the media.

When people of color are treated differently, “it destroys the credibility of law enforcement, not to mention the impact it has on people of color,” said Patricia Lally, the former director of the Seattle Office for Civil Rights, who now teaches racial equity in professional settings. “It impacts their opportunity for employment for years, maybe for the rest of their life. It impacts how they live, how they can obtain housing. It impacts and fractures families.”

About half of the 9,300 Colville members live on the state’s largest reservation, a sprawling area larger than the state of Delaware at 2,187 square miles, and more than 2,000 reside in the Omak area. The Colville Nation itself includes 12 tribes, some of which once lived as far south as Oregon and across the northern border in Canada. Those tribes were initially settled on a network of reservations sprawling over northern and eastern Washington, but were eventually forced onto a 3-million-acre reservation that stretched from the Columbia River to the Canadian border. Land grabs for farmers and gold miners eventually shrank that reservation to its current size.

The pain of that forced relocation and land theft is still felt in the Colville community, tribal leaders say. When police are camped out on the edges of reservations, or young tribal men know they’re likely to get searched every time they’re stopped, it has far-reaching consequences.

The tensions in Central Washington aren’t limited to Native Americans. The majority of Okanogan County’s residents are white. But about 20% are Hispanic and 13% are Native American. Douglas County, which borders the reservation to the south, is more than 30% Hispanic.

Manuel Farias, a 56-year-old orchard worker who lives just across the county line in Bridgeport, said the heated national rhetoric about immigration is increasing Hispanics’ fear of law enforcement. Farias said he was stopped three times in one year by state and local police and searched once. A state trooper stopped Farias on Oct. 15, 2018, in Okanogan County and cited him for driving without an ignition interlock device. Farias said the vehicle he usually drives that has the interlock device, a requirement after a drunk driving charge a decade ago, was broken down and he needed to take another car to Omak to get a new interlock device. He said he pleaded guilty in February and served 10 days in jail.

“Especially the Hispanic people, they’re the ones who are most afraid,” said Farias, who’s from Mexico but is now a U.S. citizen. “They’re afraid to go out, to take their children to school, to go out to buy food at the store.”

Immigrants swept up into the justice system are easier for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement to find, and those in the country legally stand to lose their status if they’re arrested. Despite the state of Washington limiting cooperation with federal immigration authorities, ICE has access to jail and court records. If Latinos are more likely to be searched by state police, then immigrants driving on Washington highways are more likely to face deportation, said Maru Mora-Villalpando, a Latina activist and CEO of the Seattle-based consulting firm Latino Advocacy.

One result, Mora-Villalpando said, is that immigrant communities become unwilling to call 911 when they see crimes committed or come forward to help with investigations.

“People are afraid of police,” she said. “The impacts on these communities are way, way higher.”

Ferreting out unconscious bias

Implicit bias is the focus of much public conversation today, including in the I-940 ballot measure to reduce police violence passed by Washington voters in 2018. Yet it’s something Seattle police have wrestled with for 20 years.

Jim Pugel first became familiar with the concept when he was a captain with the Seattle Police Department in the early 2000s. Police cracking down on drug sales downtown were arresting a disproportionate number of black men, sparking a lawsuit by the American Civil Liberties Union and the Public Defender Association. To settle the lawsuit, Seattle agreed to robust bias training and a well-regarded diversion program for some offenders.

“Do officers wake up and say, ‘I’m going to arrest this group or gender or culture today?’ We weren’t, but the numbers were way out of whack,” said Pugel, who later served stints as the city’s interim police chief and the chief deputy at the King County Sheriff’s Office.

Those unconscious biases can manifest themselves by police focusing on black drug users or being more likely to search a Native American driver. It breaks down relations between police and the community and undermines respect community members have for officers, Pugel said.

Being on the receiving end of a baseless police search can be “humiliating, embarrassing, inconvenient, terrifying,” said Lisa Daugaard, executive director of the Public Defender Association, a Seattle nonprofit that advocates for criminal justice reform. And when police set lower standards for searching people of color than whites, it means that whites who commit crimes are less likely to be arrested and prosecuted, creating what Daugaard called “white impunity.”

“The deepest inequities are among the people that are guilty, and some guilt just isn’t treated as equally,” Daugaard said.

Training away the bias

Could training Washington State Patrol troopers more thoroughly about implicit bias help eliminate the racial disparities in search rates? In an interview, Rachel Godsil, a Rutgers University expert on bias training, expressed concern that the patrol’s training programs are insufficient.

In response to an open records request, WSP provided documents showing cadets at the agency’s training academy attend a one-hour course on “unbiased policing,” covering stereotypes, racial profiling versus criminal profiling, immigration-related enforcement, and the history of state patrol race data collection. It asks trainees to discuss state laws and policies give examples of biased policing.

In contrast to that one-time training before joining the state patrol, the agency’s regulation manual requires troopers to attend three firearm training and qualification sessions each year.

The Washington Criminal Justice Training Commission offers a 16-hour training on “Understanding Perceptions and Bias,” with an almost singular focus on understanding, recognizing and “adapting to” implicit bias in one’s self and others. WSP does not participate in this training.

Godsil said it’s difficult to address implicit bias, aversions and preferences built up over a lifetime of experiences in a one-time training such as the one used by WSP. Even then, Godsil said, the WSP training doesn’t seem to achieve the key goals she’d like to see in a one-time discussion of implicit bias: making clear everyone is susceptible to it and laying out a framework for changing biased behavior.

In an email, Lt. Dennis Bosman of the patrol’s training division said cadets do go through “practical exercises” with actors that simulate real-life scenarios. Bias isn’t the focus of those exercises, WSP officials said, but it is addressed.

“There is some useful discussion that they (the trainees) probably have,” Godsil said. But “I can’t imagine that this content alone would achieve the bare minimum.”

The Criminal Justice Training Commission is currently developing training that will be given to all officers statewide as part of I-940, the voter-mandated law enforcement reform that also will make it easier to prosecute police who kill someone in the line of duty. Crisis intervention training required for all police in the state under a 2015 law also addresses bias, Bosman said, as did refresher courses troopers took in 2016 and 2018.

Unbiased policing is “the heart of the (bias-related) curriculum, but that curriculum is repeated and intertwined in many ways throughout the training,” Loftis said.

“That said, is that enough? Obviously the numbers say it’s not enough. We have to do more, and we have to do things differently. And again, it’s a process not an event.”

Experts have raised questions about whether training police officers about implicit bias is effective. The proposition has not been properly tested and might even be counterproductive, some experts conclude, unless carried out correctly.

Mora-Villalpando, the Latino Advocacy activist, is less than enamored with the touchy-feely rhetoric about addressing implicit bias through discussion and training. She called for more serious consequences for officers who show evidence of bias.

“We don’t see it as implicit bias. We see it as racism. It’s structural racism,” she said. “A lot of police agencies get away with it by giving training for implicit bias. They give the individual officers training and say, ‘you’re not going to do it again.’ But there’s no accountability.”

Loftis said troopers are expected to adhere to the state patrol’s anti-bias policy and can be disciplined for not doing so.

He also said the patrol has taken other steps to address bias and improve community relations. Those steps include outreach programs, improvements in how the agency records race and ethnicity data, and a recruiting focus on increasing diversity in the agency’s ranks.

InvestigateWest’s findings, Loftis said, have prompted the agency to “renew and refresh our focus” on bias, and the agency is considering again partnering with an outside organization to conduct comprehensive studies like those done by WSU last decade.

“In law enforcement, we’re not immune to societal ills,” Loftis said. “We’re just as reflective of them as any group often, but we aspire to hold ourselves to a much higher standard.”

This story was supported in part by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.