The backroom deals that saved Andrew Johnson’s presidency by a single Senate vote

President Andrew Johnson as featured in American Heritage. (Associated Press)

The impeachment trial was almost over, and Sen. James Grimes was tormented with doubt.

The Iowa senator couldn’t stand Andrew Johnson, the belligerent, racist president on trial before the Senate, charged with defying Congress and the law. Johnson was “guilty of a great many follies and wickedness,” the mustachioed, mutton-chopped Grimes had written in a letter to his wife.

Grimes feared that if the president were acquitted, he would unleash even more revenge against his enemies and stoke racial violence in the South. But the senator, a moderate Republican, also couldn’t stand the impeachers, the radicals trying to tear Johnson from the White House in the name of racial equality. He thought they’d gone too far.

So just before closing arguments began in Johnson’s trial in April 1868, Grimes sent messages to Johnson through intermediaries, including one of the president’s defense lawyers. If Johnson agreed not to engage in rash acts that might “encourage rebels” in the South, and if he nominated a “secretary of war in whom the country had confidence,” Grimes said, “it would help him” – that is, Grimes and other swing-vote senators might vote to acquit Johnson.

So amid the impeachment trial’s closing arguments, Johnson sent the Senate a nomination: Gen. John Schofield, Grimes’ suggested candidate, for war secretary. That got the senators buzzing.

“During the last 24 hours,” another of Johnson’s lawyers wrote to the president, “impeachment has gone rapidly astern.”

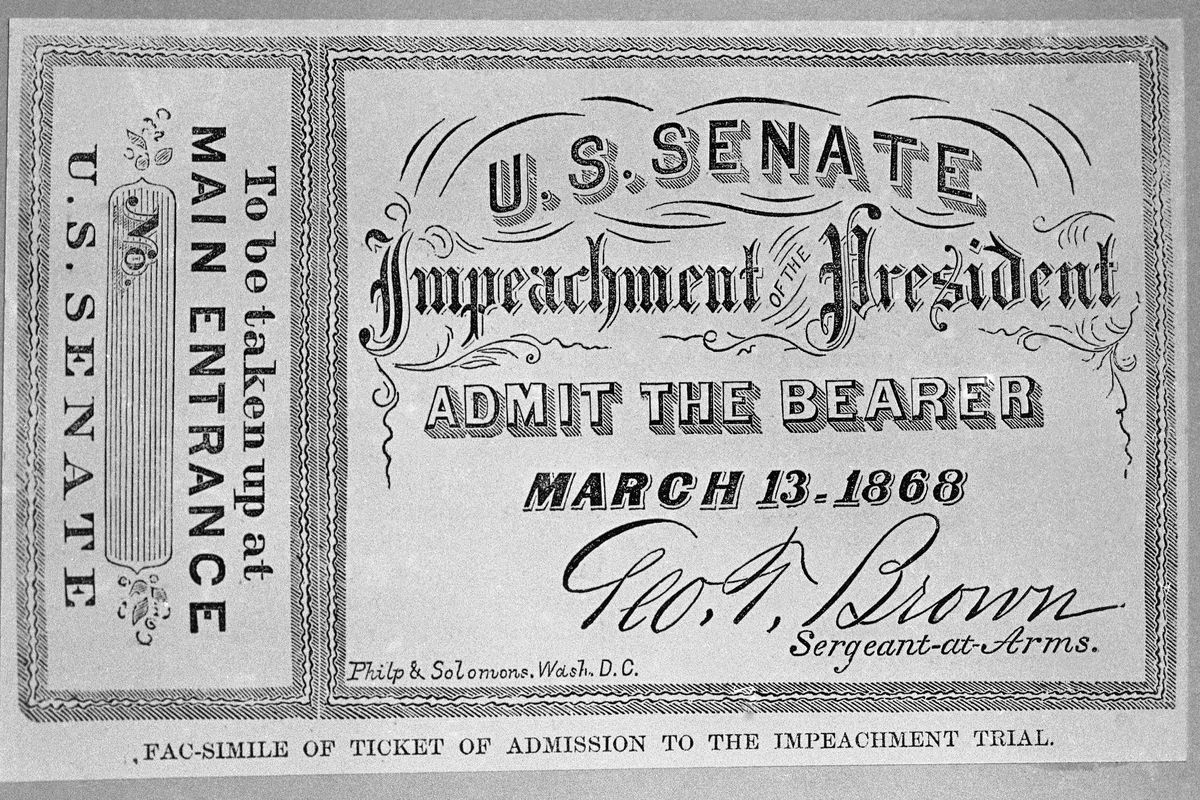

When the nation’s first presidential impeachment trial began 152 years ago, Andrew Johnson, a Democrat, was in serious danger of conviction by the Republican-dominated Senate. But the power to end a presidency also created intense pressure on the senators who would cast the deciding votes.

The same pressures are playing out this week in the Senate, which faces a critical vote in the impeachment trial of President Donald Trump. On Friday, the Senate will decide whether to call witnesses as it weighs allegations that the president pushed Ukraine to investigate his political rivals.

During the Andrew Johnson impeachment trial – the first in the nation’s history – several Republican senators cut deals with Johnson or his intermediaries before voting for his acquittal.

Last week Vice President Mike Pence praised one of them, Kansas Sen. Edmund Ross, in a Wall Street Journal op-ed. Ross was celebrated by John F. Kennedy in his 1956 book “Profiles in Courage” for his decision to defy his party and vote to acquit Johnson. Pence urged Democrats to do the same and acquit Trump.

But the authors of two books on Johnson’s impeachment say the heroic portrayal of Ross is historically inaccurate. Actually, they said, Ross received huge patronage rewards from Johnson after his vote – and he may have also taken a bribe.

The House of Representatives impeached Johnson in February 1868 after he fired Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, following a long dispute over how to govern the defeated South after the Civil War. Johnson’s impeachment, sometimes dismissed as partisan or petty, was actually an epic clash over the separation of powers, the rule of law, the legacy of the Civil War, and the fate of millions of recently liberated black Southerners.

“Slavery and thus the very fate of the nation lay behind Johnson’s impeachment,” Brenda Wineapple wrote in her 2019 book “The Impeachers: The Trial of Andrew Johnson and the Dream of a Just Nation.” “Johnson was impeached and then brought to trial in the Senate by men who could no longer tolerate the man’s arrogance and bigotry, his apparent abuse of power, and most recently, his violation of law.”

Johnson, a Tennessee Democrat elected Abraham Lincoln’s vice-president in 1864 on a national unity ticket, became president after Lincoln’s 1865 assassination. A former slave owner who’d remained loyal to the Union during the Civil War, Johnson quickly took the side of white Southerners in disputes about postwar Reconstruction. He recognized all-white Southern state governments full of ex-Confederates, stood by when they enacted “black codes” that oppressed ex-slaves, and took no action when racist mobs began to murder black Southerners. Johnson “fed the fires of rage and hate,” David O. Stewart wrote in his 2009 book “Impeached: The Trial of Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln’s Legacy.” “It was simply his rigid, combative nature.”

Congress, controlled by Lincoln’s Republican Party, passed Reconstruction laws over Johnson’s veto. They kept Southern states out of the Union and under military rule until they ratified the 14th Amendment and adopted constitutions granting black men the right to vote. Johnson, defending white supremacy, railed against the lawmakers.

“Negroes have shown less capacity for government than any other race of people,” Johnson declared in his December 1867 message to Congress, the equivalent of today’s State of the Union address.

When Johnson fired Stanton two months later, the Republicans saw it as a power play and accused Johnson of violating the Tenure of Office Act, a controversial new law meant to limit the president’s power to fire his Cabinet. But Article 11, which emerged as the strongest and most likely to result in conviction, didn’t just accuse Johnson of a crime. It also charged him with abusing his power: firing Stanton to block the execution of the military Reconstruction laws.

Johnson’s trial, which began in March 1868, often bogged down in excruciating arguments about the Tenure of Office Act’s language. The president’s lawyers argued that Johnson shouldn’t be removed from office for defying a law he thought unconstitutional.

But House impeachment managers periodically reminded the senators of the trial’s true stakes. Thaddeus Stevens, the Radical Republican advocate for black civil rights, argued that the “real purpose of all [Johnson’s] misdemeanors” was to “convert a land of freedom into a land of slaves.”

Everyone knew the final vote would be close. Then, as now, it took two-thirds of the Senate to remove an impeached president, and some senators were unsure that Johnson’s actions amounted to impeachable high crimes and misdemeanors. Out of 54 senators, nine were Democrats and would vote to acquit Johnson. So would three Republican allies. That left Johnson needing only seven more Republican votes.

After Johnson nominated Schofield to replace Stanton as war secretary, Grimes and two other Republicans declared they’d vote for acquittal. Johnson “has no thought of wrong or rash doings,” Grimes assured Senate colleagues after meeting privately with the president.

The lobbying of wavering senators grew furious. Even Ulysses S. Grant, commander of the Army and probable Republican candidate for president, urged several to vote guilty. John Henderson, senator from Missouri, told Republican leaders he might vote to convict on Article 11. But then James Craig, a Missouri railroad president and Johnson supporter, came to talk with him. Afterward, Henderson declared that he would vote to acquit, and that Johnson had promised to abide by congressional Reconstruction.

That put Ross on the spot. He, too, told fellow Republicans he would vote for the broad 11th article. But he didn’t. Twice in the hours before the vote, Ross met with Perry Fuller, an infamous fixer who had likely secured Ross his seat in the Senate. Fuller had recently met with Johnson supporters who had access to a $150,000 fund.

On May 16, 1868, Ross was among 19 senators who voted to acquit Johnson. The impeachers fell one vote short. Johnson’s presidency was saved.

Later that day, a Republican congressman saw Ross on the White House grounds. “There goes the rascal to get his pay,” the congressman scoffed.

The House launched an investigation into whether Ross, Henderson and others were bribed. It unearthed plenty of evidence that Johnson supporters had circulated dark money in Washington before the vote, but no proof connecting a senator to the cash.

Ross always denied taking money for the vote; in fact, he said he’d refused a bribe from the anti-Johnson side. “My hands have no dishonorable stain on them,” Ross told the Senate.

But Stewart, the author of “Impeached,” doesn’t buy that. “Ross’s vote was bought and paid for with patronage promises and, very likely, cold cash,” Stewart wrote last week, criticizing Pence’s op-ed.

It’s undisputed that Johnson, at Ross’s request, appointed Ross’s brother and several friends to jobs after the trial, including Fuller as collector of the port of New Orleans. One such appointment was “of vital importance to me,” Ross wrote Johnson, “in consequence of my action on the Impeachment.”

The Senate approved Schofield as secretary of war after the trial. But Johnson’s vengeful ways didn’t end. In his last 10 months in office, Johnson replaced Army generals who’d been tough on the white South and denounced congressional Reconstruction and black suffrage. On Christmas 1868, he pardoned all ex-Confederates, including former rebel president Jefferson Davis.

Still, impeachment wounded Johnson’s bid for another term in the White House. He lost the Democratic presidential nomination to Horatio Seymour at the party convention that July.

Johnson’s impeachment, Wineapple wrote in “The Impeachers,” “demonstrated that the American president was not a king,” and “that all actions have consequences.”

- - -

Erick Trickey teaches magazine journalism at Boston University.